UNBLOCKING OF UKRAINIAN PORTS AND FREEDOM OF NAVIGATION IN THE BLACK SEA: POLITICAL AND DIPLOMATIC DIMENSION

Group of authors:

Bohdan Ustymenko, Mykhailo Honchar, Oksana Ishchuk, Pavlo Lakiichuk

I. SITUATION ASSESSMENT

1. The importance of access to the sea and its own seaports for the economy of Ukraine

Ukraine has the longest sea coast among the Azov-Black Sea basin countries—2759.2 km. A significant part of the national gross domestic product is formed by five regions of Ukraine, which have access to the sea and occupy about 27% of the territory. Most of the population on their territory lives at a distance of no more than 60 kilometers from the sea and is closely connected with marine activities [1].

There are 18 seaports on the territory of Ukraine in the Black Sea-Azov basin, as well as the Danube delta, among which 13 are on the continental part: Reni, Izmail, Ust-Dunaisk, Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi, Chornomorsk, Odesa, Pivdennyi, Mykolaiv, Olviia, Kherson, Skadovsk, Berdiansk, Mariupol and 5 in the temporarily occupied territory of the Crimean Peninsula: Kerch, Feodosiia, Yalta, Sevastopol ta Yevpatoriia [2].

According to the Ministry of Economy of Ukraine, the volume of exports from Ukraine in 2021 amounted to $68.24 billion [3]. Ukraine exports more than 70 percent of its cargo from its own seaports, for a total value of about $47 billion. Just one day of Ukraine’s naval blockade damages the domestic economy by about $170 million [4].

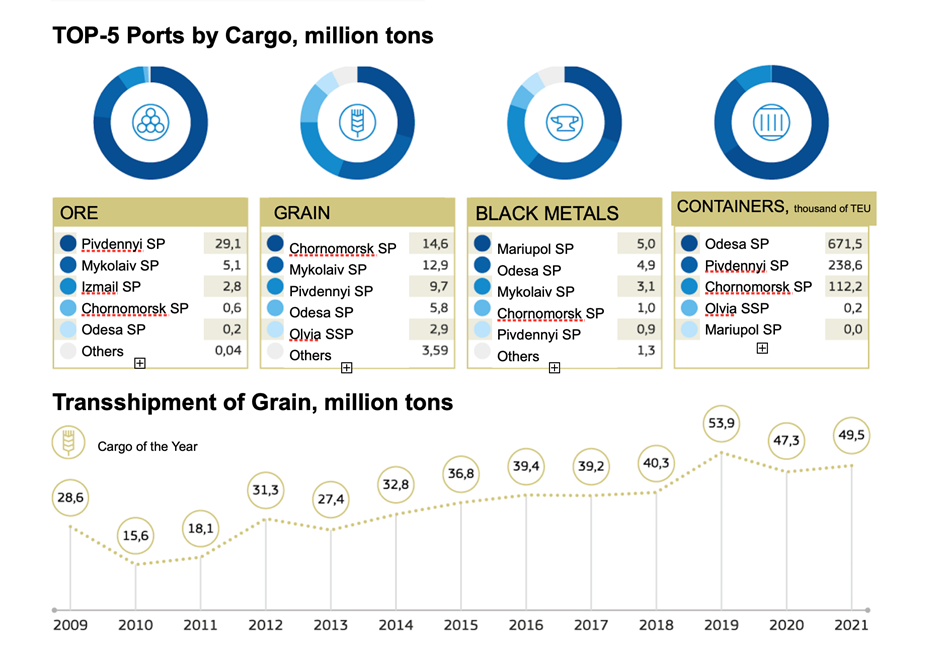

In 2021, Ukraine’s seaports handled 153 million tons of cargo, according to the Center for Transport Strategies with reference to the Administration of Sea Ports of Ukraine [5]. In 2021, operators in seaports transshipped 118.1 million tons of export cargo, and 24 million tons of import cargo. Grain cargo and ore were handled the most in the ports during the year— 49.9 million tons and 37.75 million tons, respectively. Transshipment of petroleum products for 12 months of 2021 increased by 82% and amounted to 1.93 million tons.

https://cfts.org.ua/infographics/gruzopotoki_portov_ukrainy__2021

Conclusion: access to the sea and full functioning of sea ports are of key importance for Ukrainian economy.

2. On the maritime border between Ukraine and the Russian Federation

After the collapse of the Soviet Union the maritime boundary between Ukraine and the Russian Federation in the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait has not been established in accordance with the norms of international maritime law. The border in the sea was not defined even after signing the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership between Ukraine and Russian Federation, Article 2 of which states that “The High Contracting Parties, in accordance with the provisions of the UN Charter and their obligations under the Final Act of the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe, respect each other’s territorial integrity and confirm the inviolability of existing borders between them” [6]. This has created one of the main threats to Ukraine’s national security.

Contrary to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the legitimate interests of Ukraine and other countries, two international documents were concluded between the Russian Federation and Ukraine directly concerning the legal status of the maritime spaces in the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait and illegally limiting freedom of navigation in the region:

- The Treaty between Ukraine and the Russian Federation on the Ukrainian-Russian State Border of 28.01.2003 [7], ratified by the Law of Ukraine of 20.04.2004 No. 1681-IV [8] (hereinafter—the Treaty on the Border with the RF). Article 5 of the Treaty stipulates that issues related to adjacent maritime spaces are settled by agreement between the Contracting Parties in accordance with international law. The Treaty also states that “nothing in this Treaty shall prejudice the positions of Ukraine and the Russian Federation regarding the status of the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait as internal waters of the two States”;

- The Treaty between Ukraine and Russian Federation on Cooperation in the Use of the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait of 24.12.2003 [9], ratified by the Law of Ukraine of 23.04.2004 No. 1682-IV [10] (hereinafter—the Azov Treaty). This Treaty contains provisions that the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait “are historically internal waters of Ukraine and the Russian Federation.” The Azov Treaty also stipulates that warships or other state non-commercial vessels of third states (for example, those of the U.S. or the U.K.) cannot enter the Sea of Azov and pass through the Kerch Strait without the agreement of both states—the Russian Federation and Ukraine. It should be added that the conclusion of the Treaty of Azov was the result of the threat of force by the Russian Federation—the notorious conflict around the Ukrainian island of Tuzla in the Kerch Strait in 2003.

We should note that the Treaty of Azov and Article 5 of the Treaty on the Border with the RF directly violate the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and are contrary to the interests of Ukraine and other countries, because the internal waters can belong only to one state (Article 8 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea) and not to two, as stated in the Russia-Ukraine agreements of 2003, and the Kerch Strait has an international status (Article 37 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea). The area of the Sea of Azov is large enough (about 40,000 square kilometers) to contain not only the territorial seas of the two states, but also their exclusive economic zones.

After termination of the existence of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation has in every way possible hindered establishment of maritime borders with Ukraine in the Black Sea, Sea of Azov and Kerch Strait in accordance with regulations of the international maritime law. One reason for this is that under fair delimitation of maritime spaces between two states, according to norms of UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, sovereignty and jurisdiction of Ukraine would extend to most part of the Azov Sea—about 2/3 of its total area as well as the strategically important Kerch–Yenikale canal, the trade route between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov.

3. On the seizure of Ukrainian maritime spaces and ports by the Russian Federation in 2014

Considering the internationally recognized land borders of Ukraine and the prescriptions of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the area of the territorial sea and exclusive (maritime) economic zones in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, as well as the Kerch Strait part of the territorial sea of Ukraine is about 137,000 square kilometers.

After occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol, Ukraine, as a littoral state, actually lost the possibility to fulfill rights provided by the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, in its own spaces around the Crimean peninsula, in the Sea of Azov and in the Kerch Strait. The total area of Ukrainian maritime spaces occupied by the Russian Federation in 2014 roughly equaled 100,000 square kilometers [11] (see Schematic Map 1).

In addition, as a result of the temporary occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol, the ports of Kerch, Sevastopol, Feodosiia, Yalta ta Yevpatoriia were closed as per the order of the Ministry of Infrastructure of Ukraine “On Closing the Seaports” № 255 dated 16.06.2014, registered with the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine under № 670/25 on 24.06.2014 [12]. The Resolution of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine “On Temporary Closure of Sea Fishing Ports” No. 263 of 6.04.2016 closed the Kerch and Sevastopol Sea Fishing Ports [13]. The seized Ukrainian state-owned port infrastructure on the territory of the Crimean peninsula has been illegally exploited by the aggressor for its own purposes since 2014.

Russia’s internationally illegal actions prompted the UN General Assembly to approve a number of resolutions condemning the temporary occupation and militarization of Crimea and parts of the Black Sea and Sea of Azov [14].

4. On the loss of Ukraine’s naval assets in Crimea

As a result of the temporary occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and Sevastopol by the Russian Federation, the Naval Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine were in an extremely difficult condition. Virtually, the national fleet lost more than 80 percent of its assets and capabilities, suffered significant personnel and material losses [15], which negatively affected Ukraine’s ability to take part in operations to ensure freedom of navigation in the Black and Azov Seas and the Kerch Strait.

In 2014, Russia seized more than 70 Ukrainian naval ships and vessels stationed at bases in Crimea and Sevastopol. Later, after unblocking, 35 Ukrainian naval ships, boats and vessels were brought out of the temporarily occupied Crimea to other ports of Ukraine. The rest of the ships, boats and supply vessels, including those that are combat ships—corvettes “Ternopil”, “Lutsk”, “Khmelnitskyi”, missile corvette “Prydniprovia”, control ship “Slavutych”, naval minesweepers “Chernihiv” and “Cherkasy”, large landing ship “Kostiantyn Olshanskyi”, submarine “Zaporizhzhia” and a number of other vessels and supply ships, remain in the hands of the aggressor [16]. After eight years of unattended anchorage these units can be considered as technically permanently lost.

5. On the loss of access to the Ukrainian offshore fields

Significant hydrocarbon reserves have been explored on the Ukrainian shelf of the Black and Azov Seas, including up to 1,583.5 billion cubic meters of natural gas and up to 409.8 million tons of crude oil, which accounts for more than 30 percent of Ukraine’s total hydrocarbon reserves. It was predicted that Ukraine’s gas production would increase by one-third, that is, by 10 billion cubic meters per year, only through the development of fields on the shallow Black Sea shelf [17].

The pre-war period, until 2014, was characterized by the fact that the Ukrainian government had concluded production sharing agreements (PSAs) with transnational companies that were among the top 10 global energy corporations. Natural gas from offshore fields and unconventional sources was supposed to be the key to success. According to the forecast of IHS CERA experts in 2012, gas production in Ukraine by 2035 could reach up to 73 billion cubic meters per year [18].

Considering this and Russia’s traditional penchant for creating anti-competitive and monopolistic schemes, one of the motives behind the occupation of Crimea was energy. Under such circumstances, taking into account the proximity of Ukrainian gas fields to the EU, gas of its own production would not only satisfy all the needs of Ukraine, but would also be exported to Central and Eastern European countries, displacing Russian gas. Thus, Moscow assessed that under such a scenario, Gazprom would not only lose its market in Ukraine, but could also encounter some competitive pressure on the markets of Central and Eastern Europe.

Therefore, the occupation of the Crimean peninsula and the nearby shelf zone gave Russia a solution to strategic issues:

- liquidation of promising gas exploration and production projects in the Black Sea, initiated by Ukraine with the involvement of European and American companies, which became a challenge for Russian state-owned companies;

- forcing leading American and European oil and gas companies, which are traditional competitors of Russian state-owned companies, out of the northern sector of the Black Sea;

- complicating Ukraine’s access to the main part of the offshore gas fields and prospective hydrocarbon reserves in the Black Sea.

Since March 14, 2014, Ukraine has not had access to its own fields located in the northwestern sector of the Black Sea—the new “Petro Hodovanets” and “Nezalezhnist” jack-up drilling rigs and the old ones “Syvash” and “Tavryda” were seized by the Russian Armed Forces [19 ].

As a result of the seizure of Ukrainian extraction assets in the Black Sea shelf, during the period from March 2014 to December 2021 inclusive, the illegal extraction amounted, according to the authors’ calculations, to 14.2 billion cubic meters of natural gas.

6. Russia’s use of offshore gas infrastructure for military purposes

Captured by Russian special forces in March 2014 during the operation to occupy Crimea, production and drilling platforms of the Ukrainian state company Chornomornaftogaz became a convenient platform for the development of forms and methods of radio and radiotechnical reconnaissance of the Russian Black Sea Fleet using the capabilities of the civil maritime infrastructure in the northwestern part of the Black Sea. The Russian Federation deployed a comprehensive system of surface and underwater monitoring in order to detect surface, underwater and low-flying air targets. [20]

After the start of hostilities at sea on February 24 this year, additional radio reconnaissance and radiotechnical warfare stations were installed on production platforms and jack-up rigs. Practically, there was formed a center for coordination of efforts of diverse strike forces for the purpose of landing and seizure of the coast of Odesa region [21]. As a consequence, Russian radars, radiotechnical reconnaissance and electronic warfare facilities on the seized assets were destroyed by a fire strike of the coastal complexes of the Ukrainian Navy.

7. On the naval blockade of Ukraine in 2022

Russia began its first attempts at a naval blockade of Ukraine before the invasion on February 24, 2022. In December 2021, Russia blockaded sea routes in the Sea of Azov for a long time because of so-called “planned exercises” of the military fleet. Then the Russians effectively restricted navigation in 70% of the Sea of Azov. On February 13, in the run-up to the invasion, under the pretext of another “fleet exercise,” Russia blocked navigation in large areas along the Ukrainian coast of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. Due to Russia’s blocking of sections of the Sea of Azov, the movement of merchant ships to Ukrainian ports stopped entirely —the Russians completely closed the Kerch Strait, and in the Black Sea, ship traffic was significantly limited because the closed areas overlapped the recommended routes for most merchant ships [22].

After the full-scale invasion began on February 24, 2022, ships of the Russian Black Sea Fleet repeatedly shelled and sank merchant ships flying the flags of different nations (see Appendix 1). Due to the Russian military aggression against Ukraine, according to the order of the Ministry of Infrastructure of Ukraine “On the Closing of the Seaports” No. 256 dated 28.04.2022, registered with the Ministry of Justice of Ukraine on 29.04.2022 under No. 470/37806, the Ministry of Infrastructure of Ukraine closed Berdiansk, Mariupol, Skadovsk and Kherson [23].

Conclusion: given the above facts, all Ukrainian Black Sea and Azov ports turned out to be illegally blocked from the sea by the aggressor state of Russia.

8. On Russia’s seizure of the Kakhovskyi lock in 2022

It should be pointed out that the Kakhovskyi lock on the Dnipro River, which is strategically important for Ukraine, was seized by the Russian Federation [24]. Also, the section of the Dnipro from the Kakhovka reservoir together with its left bank and to the river mouth in the Dnipro-Buh estuary is captured by the enemy, controlled by it and is within the zone of military operations. As a consequence, navigation on the Dnipro is restricted, the exit from the Dnipro to the Black Sea and the entry of ships from the Black Sea to the Dnipro in this regard is impossible. This circumstance further significantly complicates transport communication in the state, including the export of Ukrainian agricultural products and other goods. Transportation of cargo, particularly grain, along the Dnipro River to the seaports of Kherson and Mykolaiv has become out of the question.

9. On the situation on the Danube in the context of Russian aggression

Ukrainian ports on the Danube River were not seized by the aggressor and did not stop their operation after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the Russian Federation. After 24.02.2022 the turnover of cargo through these ports increased by 2.5–5 times [25].

In the context of navigation on the Danube, it should be mentioned that in 1998, the aggressor state, which is not a Danube country, without proper legal grounds obtained the status of a member of the Danube Commission, a body with key powers in ensuring navigation on the river, according to the Convention regarding the Regime of Navigation on the Danube. In the international document on granting the Russian Federation the status of a member of the Danube Commission, it is effectively stated that the Russian Federation is the legal successor of the USSR [26]. At the same time, the Russian Federation is not and has never been the legal successor of the Soviet Union, a former member of the Danube Commission, that is confirmed by the USSR Constitution, the Moscow Treaty, the Belavezha Accords and other documentary evidence [27].

The presence of the aggressor as a full member of the Danube Commission is not only unlawful, but also a threat to the maritime security of both Ukraine and the entire northwestern Black Sea and Danube basin.

10. On the Russian military threat in the Black and Azov Seas

Since the beginning of the large-scale invasion, the Russian Black Sea Fleet, as well as ships, units and subunits of other Russian fleets have been taking part in the offensive operation of the Southern Military District of the Russian Armed Forces in cooperation with units and formations of the 8th and 58th Combined Armies, the 4th Air Forces Army, operating from naval bases and locations in the occupied Crimean peninsula and the Krasnodar Territory of Russia [28].

During this time, the Russian Black Sea Fleet carries out the tasks of assisting the actions of ground troops in the coastal area, the naval blockade—isolation of areas of combat operations and missile strikes on infrastructure facilities on the territory of Ukraine. Enemy ships and submarines are striking with cruise missiles against industrial and infrastructure facilities in strategic depths of Ukrainian territory. Threats of missile strikes and amphibious landings persist.

Since the start of the invasion, the Russians have lost 15 ships and vessels at sea destroyed and damaged, including the flagship of the Black Sea Fleet, the missile cruiser “Moskva” (struck by two Neptun missiles on April 14, 2022), the large landing ship “Saratov” (sunk on March 24, 2022 in the port of Berdiansk), the sea rescue tug “Vasily Bekh” (destroyed by a Harpoon missile near Zmiinyi Island on June 17, 2022) [29].

From June 20 to July 1 the Ukrainian Armed Forces carried out an operation to destroy enemy forces that captured Zmiinyi Island, defeat enemy air defense facilities on it, as well as the Russian Black Sea Fleet surveillance system over the surface and air situation in the northwestern part of the Black Sea. Zmiinyi Island holds strategic importance, as it enables it to control the surface and part of the air situation in the South of Ukraine. The final liberation of the island on July 7 this year allowed to ensure the transportation of agro-products by civilian ships through Bystre estuary of the Danube-Black Sea shipping channel. However, the danger of sabotage through this channel remains. Thus, on July 31, the passage of the Bystre estuary was temporarily restricted for vessels due to a collision with an explosive device of the pilot boat “Orlyk” of the “Delta-lotsman” branch of the state enterprise “Administration of Sea Ports of Ukraine” while performing a pilot voyage outside the route of the vessels [30]. Previously, due to Russia’s blockade of civil navigation, companies used only the Romanian Sulina channel, which led to a large accumulation of ships to reload the channel.

After heavy losses in ships from strikes on Ukrainian anti-ship missiles, the liberation of Zmiinyi Island, and the destruction of the surveillance system in the northwestern part of the Black Sea, the Russians were forced to withdraw their ship grouping to the coast of Crimea, under the protection of coastal air defense complexes.

The spokesman for the Main Directorate of Intelligence of the Ministry of Defence of Ukraine described the changes in the Russian Navy’s activities in the Black Sea as follows: “They have become cautious, but their ship grouping to date […] provides full control of the Sea of Azov […] together with the Kerch Strait, and they block our ports in the Black Sea. The goal is to prevent the ports from functioning as economic zones. To not allow the movement of goods both on the territory of Ukraine and from the territory of our ports, and maintain readiness to use the largest landing ships and other ships in the event of a sea landing operation. But […] our actions have forced them to limit the activities of the Russian Black Sea Fleet at this stage.” [31]

II. PROJECTIONS AND PROSPECTS

1. Doctrinal vector of Russia

The Marine Doctrine of the Russian Federation approved on July 31, 2022 in the part regarding the Black and Azov seas, proclaims “comprehensive strengthening of Russia’s positions in the region,” improving and reinforcing the groups (forces) of the Black Sea Fleet, developing its infrastructure in the Crimea and the coast of the Krasnodar Territory and “further developing the export gas transport infrastructure, including the system of underwater pipelines” [32].

Consequently, Russia is projected to continue its course of expansion in the Black Sea, both by military and hybrid means. Securing its de-facto status as the “Russian lake” with power, geopolitical and geo-economic dominance in it remains a high priority for the current Russian regime.

It is possible that in the event of referendums on the accession of the occupied territories of Ukraine to Russia in September 2022, the Sea of Azov may eventually be proclaimed internal waters of the Russian Federation. Perhaps, through an intermediate stage of the “common sea” of Russia and the pseudo-state proxy “Donetsk People’s Republic”.

Thus, return of control over maritime spaces through de-occupation of Crimea, the south and the east of the country, delimitation of maritime spaces and borders of Ukraine in accordance with international maritime law, removal of the threat of further blockade by Russia of the ports in the Azov-Black Sea basin, are of vital importance for Ukraine. This should be carried out and consolidated both through military means and appropriate political and legal actions, including interaction with Western partners.

In the context of countering Russia’s expansionism, it seems important to form a clear position of the European Union, as an association of countries, which includes those of the Black Sea. The EU is concerned over the issue of freedom of navigation in the South China Sea in the context of China’s ambitions, although it has no access to the Pacific Ocean and does not border the region. At the same time, issues of the neighboring Black Sea region have still not become a priority for the EU, although, as Russia’s blockade of Ukrainian ports shows, this approach is extremely short-sighted and should be reconsidered.

2. Istanbul Initiative as a challenge for Ukraine

On July 22, 2022 in Istanbul, the Initiative for the Safe Transportation of Grains and Foodstuffs from Ukrainian Ports was signed by the Republic of Türkiye, the Russian Federation and Ukraine at the proposal of the UN Secretary-General (hereinafter—the Initiative) [33]. The aim of the Initiative is to promote safe navigation for the export of grain and related foodstuffs and fertilizers, including ammonia, from the ports of Odesa, Chornomorsk, and Pivdennyi.

This agreement calls for all Parties to provide maximum assurances of a safe and secure environment for all vessels participating in this Initiative. In particular, the Parties will not commit any attacks on merchant ships and other civilian ships and port facilities participating in the Initiative. At the same time, the Russian Federation violated its obligations on the very next day, on July 23, 2022 by launching missile attack on the port of Odesa. Two missiles hit the port infrastructure and two more were shot down by the air defense system [34].

But on August 1, 2022 the first merchant ship loaded with corn, despite the potential danger from the Russian Federation, left the port of Odesa and on August 3, 2022 it was inspected in Istanbul, according to the terms of the Initiative [35].

It is also quite possible that further developments will follow—after some time Russia will violate the terms of the Initiative and will again try to occupy Zmiinyi Island of Ukraine in order to place its military assets and contingent there, as well as to continue shelling merchant ships.

Another threat is a potential Russian attack on Moldova and seizure of its port infrastructure and coastline along the Danube, which could lead to blocking transportation of Ukrainian goods by the river.

The authors believe that if Russia does not fulfill its obligations under the Initiative and continues to impede the freedom of navigation in the Black Sea and the Danube, then there will be the only option of deblocking Ukrainian ports and coast—a military one. This is explained by the fact that long-term Russian sea blockade of port infrastructure and violation of the principle of freedom of navigation in Ukrainian sea areas will lead to critical deterioration of Ukrainian economy and starvation of tens of millions of people in North African and Middle Eastern countries, who depend on Ukrainian grain and food.

Moreover, if the plan of full occupation of the territorial sea, the exclusive maritime zone of Ukraine and Zmiinyi Island in the Black Sea is successful for Russia, the aggressor will demand revision of the maritime border between the captured sea areas and Romania, which will lead to an armed conflict between NATO and Russia.

The U.S. and NATO have no security strategies of their own in the Black Sea, which is a critical problem for the security architecture of the entire region, including NATO member states Bulgaria and Romania.

The only real step to ensure security in the Black Sea since February 24 this year was when partners gave Ukraine anti-ship Harpoon missile systems, which significantly reduced, though not eliminated, Russian aggressive activity in the north-western part of the Black Sea. The reason, in particular, is the limited number of launchers and missiles, which makes it impossible to achieve parity with the enemy. The continuation of supplies of domestic Neptun SAMs to the AFU, as well as foreign systems like Harpoon, Exocet, NSM, both coastal and airborne, will lead to the loss of Russia’s dominance in the sea and make it act within the framework of the international maritime law.

Another hypothetically possible way is the organization of control and ensuring freedom of navigation in the international waters of the Black Sea by the naval forces of the Black Sea NATO member-states—Türkiye, Romania, Bulgaria, as well as by the ships of non-Black Sea members of the Alliance. This can be framed as a NATO-led peacekeeping operation with the formation of a task force in the Black Sea. However, judging by the indecision of NATO and the U.S. on this issue, as well as the “special position” of Türkiye, it looks unlikely.

We can also assert that the PRC is closely observing the reactions of NATO and the United States with regard to Russian aggression and drawing appropriate conclusions. If the West “skips a beat” in the Black Sea and shows indecision, it will undoubtedly have even worse consequences for itself in the South China Sea and the Arctic.

As a consequence, a long-term military conflict in the Black and Azov Seas and the Kerch Strait, an improper response to Russia’s aggressive behavior, will have extremely negative consequences for states far beyond the region, and will directly threaten international peace and security.

ІІІ. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS TO THE STATE AUTHORITIES

The Black Sea is the “heart” of the wider Black Sea region. The state, which dominates the Black Sea, dominates the whole region and is able to influence the adjacent ones—the Eastern Mediterranean and the Caspian Sea region. After the illegal forcible seizure of most of the maritime spaces of Ukraine and Georgia (maritime zone adjacent to the Abkhaz Autonomous Republic), the Black Sea is dominated by the Russian Federation.

Between February 24, 2022 and August 1, 2022, the estimated damage to Ukraine caused by the Russian Federation’s maritime blockade may amount to more than $27 billion.[36]

Due to the blockade of seaports, which accounted for approximately 80% of Ukraine’s agricultural exports prior to the full-scale invasion, food is exported exclusively through the Danube ports, railway and road checkpoints on the western borders. But their throughput capacity is insufficient to fully replace seaports. In particular, in June 2022, the available logistics routes managed to export approximately 2.5 million tons of products, while the monthly demand for the export of such products is 8 million tons [37].

Taking into account all of the above, we consider it necessary to provide the following recommendations to the state authorities in Ukraine:

- To form the Coordinating Council under the President of Ukraine on strengthening maritime security of Ukraine, which should include leading domestic non-governmental experts;

- To review the Maritime Security Strategy of Ukraine, approved by the decision of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine from 11 February 2022. The new version of the Strategy should envisage the creation of a mechanism with the main task of permanent coordination and control over the activities of security and defense sector actors that ensure maritime security;

- To work out a draft resolution of the U.S. Congress on Strengthening Maritime Security of Ukraine and initiate its consideration by the U.S. Congress in order to obtain additional assistance for the maritime security sector of Ukraine;

- To develop and adopt a joint U.S.-Ukrainian Strategy to Ensure Freedom of Navigation in the Black and Azov Seas and the Kerch Strait, as well as an Implementation Plan for this Strategy (taking into account Section II, Clause 4 of the current Charter of Strategic Partnership USA-Ukraine);

- To develop and adopt a joint British-Ukrainian Strategy to Ensure Freedom of Navigation in the Black and Azov Seas and the Kerch Strait, as well as an Implementation Plan for this Strategy;

- To take possible measures to develop and adopt a NATO Strategy to Ensure Freedom of Navigation in the Black and Azov Seas and the Kerch Strait;

- To work through inter-parliamentary lines on the issue of adopting a European Parliament Resolution on Strengthening Maritime Security in the Black Sea Region and Ensuring Freedom of Navigation;

- To initiate the development and signing of a common Maritime Security Strategy of the associated trio states—Georgia, the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, as well as an Implementation Plan for this Strategy;

- To adopt a law on termination (denunciation) in respect of Ukraine of the Agreement on the Establishment of the Black Sea Naval Cooperation Task Group (BLACKSEAFOR) with the participation of the Russian Federation;

- To initiate the establishment of a new regional Black Sea naval formation in order to ensure freedom of navigation in the Black and Azov Seas and the Kerch Strait, to draft a relevant multilateral international treaty (possibly not only with the Black Sea countries);

- To take measures aimed at establishing a special subsidiary body of the UN Security Council to quickly and effectively address issues relating to the support of international peace and security in the Black Sea region on the basis of the UN Charter, in particular Article 29 of this document;

- To refer the dispute regarding delimitation of the maritime boundary between Ukraine and the Russian Federation in the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait based on Article 298 and Section 2 of Annex V of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea for settlement by (compulsory) conciliation;

- To adopt a law on denunciation of the Treaty between Ukraine and Russian Federation on Cooperation in the Use of the Sea of Azov and the Kerch Strait;

- To conduct a verification (review) by the state apparatus with the involvement of representatives of the expert community of all international treaties and existing formats of cooperation, which were used, are used or may be used in the future by Russia to damage the national interests of Ukraine, including at sea. After such verification (review), all appropriate measures should be taken, including legal, diplomatic and political ones;

- To develop a practical mechanism for large-scale recovery of compensation from the Russian government for expropriated Ukrainian assets/investments in Ukraine (in its maritime areas) based on Article 5 of the Agreement between the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine and the Russian Government on the Promotion and Mutual Protection of Investments;

- To hold an international forum under the auspices of the President of Ukraine on strengthening maritime security in the Black Sea region (this could become an annual forum).

Appendix 1

Regarding merchant ships shelled by the Russian Federation since February 24, 2022

On February 24, 2022 a Russian bomb hit the Turkish ship “Yasa Jupiter” (flying the flag of the Marshall Islands) [38].

On February 25, 2022, two Russian missiles struck the bunker tanker “Millennium Spirit” (Moldovan flag), which had a large amount of fuel oil and diesel fuel on board, anchored not far from the port of Pivdennyi [39]. The tanker, drifting in the territorial sea without a crew and with residual diesel fuel on board, was attacked for the second time on July 7, when it was hit by an X-31 rocket fired from a Russian aircraft in the airspace over the Black Sea.

On February 26, 2022, Russia illegally and forcibly closed the area in the northwest part of the Black Sea, actually within the territorial sea and the exclusive economic zone of Ukraine. “The presence of ships and vessels in the area will be regarded as a terrorist threat,” reads a message that the Russian Navy disseminated through open shipping security channels [40].

On March 16, 2022, the Panamanian Maritime Administration reported that three civilian vessels flying the Panamanian flag, namely “Namura Queen,” “Lord Nelson,” and “Helt,” were fired upon by Russian missiles [41].

On April 4, 2022, the aggressor state shelled the civilian merchant dry cargo ship Azburg (flag of the Dominican Republic), which was in the port of Mariupol [42].

References

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1307-2009-п#Text

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/548-2013-р#Text

- https://www.me.gov.ua/News/Detail?lang=uk-UA&id=0e7f1abd-a4a4-4cd3-99e4-90d0ac4427c5&title=Minekonomiki-EksportUkrainskikhTovarivZa2021-RikSiagnuvRekordnikh68-24-MlrdDolariv

- https://forbes.ua/inside/morski-vorota-na-zamku-yak-pratsyuyut-zablokovani-cherez-viynu-porti-21042022-5552

- https://cfts.org.ua/news/2022/01/11/morskie_porty_ukrainy_perevalili_153_mln_tonn_gruzov_v_2021_godu_68497

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/643_006#Text

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/643_157#Text

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1681-15#Text

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/643_205#Text

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/1682-15#Text

- https://cs.detector.media/community/texts/184320/2021-05-09-rosiya-okupuvala-try-chverti-nashogo-morya-chomu-ukraina-tsym-ne-pereymaietsya/

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/z0690-14#Text

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/263-2016-%D0%BF#Text

- https://mfa.gov.ua/news/zayava-mzs-ukrayini-z-nagodi-somoyi-richnici-rezolyuciyi-generalnoyi-asambleyi-oon-teritorialna-cilisnist-ukrayini

- https://armyinform.com.ua/2021/12/06/vms-zs-ukrayiny-vid-radyanskoyi-spadshhyny-do-suchasnyh-standartiv-chastyna-3-perezavantazhennya/

- Кораблі ВМС України в Криму: брати чи не брати? Український тиждень 18.01.2018 https://tyzhden.ua/Society/207703

- Ukraine’s gas sector development in the context of EU interation, 2014, Razumkov centre, https://www.razumkov.org.ua/upload/1392734130_file.pdf

- https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/ihs-cera-chairman-ukraine-bears-a-potential-to-produce-70-billion-cubic-meters-of-gas-annually-138080948.html

- «Війни-ХХІ: полігібресія Росії». Центр глобалістики «Стратегія ХХІ». Київ, 2017. C. 157, https://geostrategy.org.ua/storage/app/public/files/nodes/1/book/1/Xa8si15867659506KcE7.pdf

- https://zn.ua/ukr/international/gazovi-potoki-podviynogo-priznachennya-286349_.html

- https://www.svoboda.org/a/soldatiki-ih-ohranyali-ukrainskiy-udar-po-vyshkam-v-chernom-more/31913548.html

- Часткова блокада Азовського та Чорного морів. Що кажуть експерти. Суспільне-новини. 17.02.2022 https://suspilne.media/208054-castkova-blokada-azovskogo-ta-cornogo-moriv-so-kazut-eksperti/

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/z0470-22#Text

- https://landlord.ua/news/try-porty-v-ukraini-zdiisniuiut-pryiom-i-vidpravku-vantazhiv/

- https://www.ukrinform.ua/amp/rubric-economy/3534787-vantazoobig-cerez-ukrainski-porti-na-dunai-zris-za-pat-misaciv-u-255-raziv-smigal.html

- https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/995_140#Text

- https://informnapalm.org/ua/radbez-oon-russia/

- Оперативне зведення ГШ ЗСУ. 23.05.2022 https://www.facebook.com/GeneralStaff.ua/posts/323526419960443

- Збройні сили України вразили вже 15 одиниць Чорноморського флоту РФ. NewsUA. 17.06.2022 https://newsua.one/news-military/67777.html

- Прохід гирлом Бистрим на Одещині обмежили: підірвався катер. Європейська правда. 31.07.2022. https://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2022/07/31/689838/

- Скібіцький: дії України обмежили діяльність російського флоту в Чорному морі. Радіо Свобода – Крим.Реалії https://ua.krymr.com/a/news-rosia-dii-ukrainy-obmezhyly-dialnist-rosiyskoho-flotu-v-chornomu-mori/31866636.html

- http://kremlin.ru/acts/news/69084

- https://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2022/07/22/689518/

- https://tsn.ua/ato/rosiyani-atakuvali-raketami-odeskiy-morskiy-torgoviy-port-2117305.html

- https://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2022/08/3/689958/#:~:text=Судно%20Razoni%20під%20прапором%20Сьєрра-Леоне%20вийшло%20з%20порту,борту%20перебуває%20близько%2026%2C5%20тис.%20тонн%20кукурудзи.%20Нагадуємо%3A

- https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-economy/3528363-rf-vkrala-v-ukraini-zerna-ta-olijnih-kultur-bils-ak-na-600-miljoniv.html

- https://mtu.gov.ua/news/33602.html

- https://www.eurointegration.com.ua/news/2022/02/24/7134601/

- https://www.unian.ua/war/korabli-v-odesi-stalo-vidomo-yaki-sudna-bachili-odesiti-foto-i-video-novini-odesi-11803314.html

- https://www.ukrinform.ua/amp/rubric-ato/3413740-flot-agresora-ogolosiv-pro-kontrteroristicnu-operaciu-v-ukrainskih-vodah.html

- https://www.reuters.com/world/panama-says-three-ships-hit-black-sea-since-start-ukraine-war-2022-03-16/

- https://www.facebook.com/permalink.php?story_fbid=4716130228516153&id=100003576664760

© Centre for Global Studies «Strategy ХХІ»

Group of authors: Bohdan Ustymenko,

Mykhailo Honchar, Oksana Ishchuk, Pavlo Lakiichuk

The information and views set out in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine.

Centre for Global Studies «Strategy ХХІ»

Shchekavytska str, 51 office 26

Kyiv, 04071, Ukraine

Е-mail: info@geostrategy.org.ua