THE RISE OF LEFTIST FORCES IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN: IMPLICATIONS FOR UKRAINE

Author:

Oleksii Otkydach

Today, the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean experience the so-called “second pink tide”. The latter means that most of the countries in the region are ruled by governments of a leftist/left-of-center orientation. It is typically perceived that political forces in this spectrum have a more positive attitude toward Russia, and thus, in the context of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, take a pro-Russian position. Also, the victory of left-wing political forces in a number of countries in the region is often seen as an indicator of the systemic strengthening of the leftist agenda in Latin America. An analysis of the main socio-political trends of the 2000s and 2020s, as well as a comparison of the personalities of the second pink tide with each other, demonstrate that the above statements are not correct. The first pink tide of the 2000s and 2010s was much more pro-Russian than the second tide in the 2020s. Politicians of the second pink tide are widely discordant on both domestic and foreign policy. The public demand for change and reform in Latin America is substantial, and only by sheer coincidence did the left-wing forces win the elections. In many cases, the electoral gap with right-wing candidates was minimal. Although the LAC countries support Ukraine at the UN, their limited knowledge of Eastern European history and Russian propaganda prevent this support from growing stronger.

Problem overview

Since October 2022, most Latin American countries have been led by leftist governments that are perceived to be less friendly to Ukraine and relatively loyal to Russia and Putin. These governments are referred to as the “second pink tide” because of their ideological affinity for communism, which is traditionally associated with the red color. The beginning of the second pink tide is considered to be the victory of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO for short) in the Mexican presidential election in 2018, and its final formation is considered to be the victory of Lula da Silva in the Brazilian presidential election in the fall of 2022. Between 2018 and 2022, Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Honduras, and Peru also slipped into the pink tide. For a long time, leftist governments have been in power in Venezuela, Nicaragua, and Cuba. This situation raises two questions: how systemic is the phenomenon of the second pink tide, and are these governments actually loyal to Russia?

Situation analysis

How did it all start?

The first pink tide lasted from about 2000 to 2010, in some cases even until 2014-2015. It covered almost all Latin American countries in the region, with the exception of Mexico, Colombia, and Chile. The duration of this tide is partly explained by high prices for raw materials on the world market (oil, metals, agricultural raw materials), which allowed for the maintenance of extensive social programs without complex economic or political reforms. In addition, the first pink tide united some very bright and powerful leaders. The symbol of this period is undoubtedly Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez. Others worth mentioning are Rafael Correa in Ecuador, Evo Morales in Bolivia, the Kirchners in Argentina, and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in Brazil, who became the only politician to hold power in both pink tides.

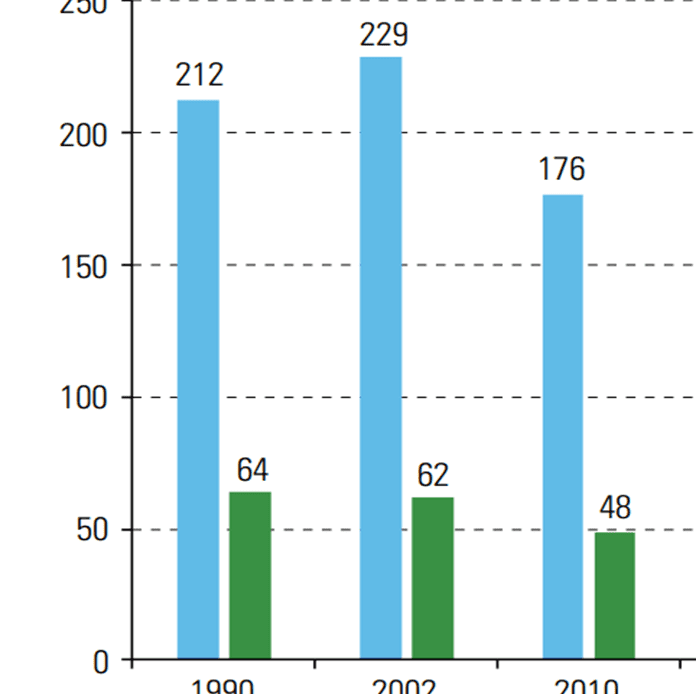

What factors influenced the emergence of the first pink tide? The main factor was the deep economic crisis of 1990, which was caused by the failed neoliberal reforms that included widespread privatization of large enterprises, cuts in social programs, and tight monetary policy. While in the early 1980s there were about 50 million people below the poverty line in Latin America and the Caribbean, in 1998-1999 this figure reached about 212 million. In Brazil, up to 50% of the population lived in homes without bathrooms, and in the Argentine capital of Buenos Aires, one in five children were malnourished. About 50% of children in Latin America did not even finish primary school. The economic crisis gave rise to a deep social crisis. From 1984 to 1994, the number of murders in the region increased by 44%.

Problem was that the mentioned reforms, carried out in a flawed Latin American political and legal climate, led to the rapid enrichment of a very narrow circle of local elites, increased poverty and corruption. As the reforms were carried out in cooperation with the United States, the IMF, and the World Bank, the perception that these measures were the result of U.S. imperial policy and aimed at deepening the economic exploitation of Latin America spread. These sentiments were exploited by left-wing leaders who proposed to end cooperation with Western financial institutions and to nationalize entire industries under the slogan of a more equitable distribution of income. These circumstances of the formation of the first pink tide explain the robust anti-Western rhetoric of Latin American leaders in the 2000s, as well as their desire to a) deepen regional cooperation (“we are together against everyone else”), b) enhance cooperation with Russia, China, India, and South Africa (on the principle of “dealing with anyone, but not with the West”). It was during the first pink tide that efforts by Lula da Silva and the rather active participation of Nestor Kirchner led to the creation of the BRICS grouping, designed to boost cooperation between the above countries.

The end of the first pink tide

Thanks to a favorable foreign policy and economic environment, representatives of the first pink tide managed to achieve tangible success. During the 2000s, the number of people living in poverty in Latin America fell from about 50% to 25%. In numerical terms, the number of poor people decreased from about 229 million at its peak in 2003 to 176 million in 2010. The number of children completing a full school education increased by an average of 10-15% in all countries of the region.

However, despite the quite significant successes in the 2000s, the golden age of the first pink tide is over. Global commodity prices, which drive the vast majority of Latin American economies, began to fall rapidly. The drop in oil prices in 2013-2014, which hit Venezuela’s economy the hardest, was indicative in this regard. At the same time, during the 2000s, the governments of the pink tide were unable (and at times did not really want to) to carry out structural political and economic reforms aimed at increasing labor productivity, developing small businesses, protecting property rights, improving the law enforcement system, investment climate, etc.

A good illustration in this context is the steady growth of the commodity sector in Latin America during the 2000s, which eventually trapped the region’s countries in an even greater dependence on the export of cheap resources than in the late 1990s. As a result, when the easy commodity money ran out in the early 2010s, almost all Latin American countries found themselves in a deep crisis. Thus, since 2010, GDP growth rates in the entire region have fallen from 4-5% per year in the 2000s to 0.5-1% in the 2010s.

It was under these conditions that the “blue tide” of right-wing governments washed over the region in the 2010s—Bolsonaro in Brazil, Peña Nieto in Mexico, Macri in Argentina, and others. The leaders of the blue tide tried to change the policy in their countries nearly 180 degrees. Instead of confrontation with the West, they have tried to intensify cooperation. And instead of government intervention in the economy, they aimed to increase the private sector. But, as you might have guessed, while this article is about the second pink tide, the blue one did not last long. This was due to the fact that even a 180-degree change in certain social or economic policies did not solve the key issues of social demand in Latin America.

The main challenge faced by Latin American elites during both the pink tide in the 2000s and the blue tide in the 2010s was to build an inclusive society, which would mean broader and more equitable access to economic and political life. This includes poverty alleviation, economic restructuring and moving away from dependence on raw material exports, reducing corruption, and addressing the social causes of crime and drug trafficking. It is also worth mentioning the need for greater integration and improvement of the situation of indigenous peoples and communities of African descent, a highly sensitive matter for Latin America. A particular focus should be on the “woman’s issue” since the countries of the region are dominated by a patriarchal social model in which women are at a disadvantage.

Causes of the second pink tide

The electoral pendulum that swings left and right is a clear indication that neither the first pink tide nor the blue tide has managed to overcome the most fundamental socio-economic problems in Latin America. The fact that a series of right-wing governments in the 2010s could not cope with the key social demands of Latin American societies was one of the most significant reasons for the emergence of the second pink tide. In 2020, the number of people living below the poverty line again reached 200 million. The overall crime rate in the Latin American region remained virtually unchanged. The only difference is that, for example, in Colombia, it has halved, while in Mexico it has doubled. Therefore, given that the era of right-wing governments in Latin America coincided with times of crisis, it is fairly certain that in the 2020-2022 elections, one of the factors that played in favor of the left was a kind of nostalgia for the stable, well-fed and happy 2000s.

In 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic added to the unresolved problems listed above. First, it greatly exacerbated the crises that already existed in Latin American societies. The poor have become poorer, and vulnerable communities of African descent and indigenous peoples—even more vulnerable. All of this contributed to the image that the governments in power at the time of the pandemic were not coping with the challenges they faced. Accordingly, society was becoming more and more inclined to entrust a country’s governance to other political forces.

It can be assumed that in those countries where governments have not handled the pandemic and all of the accompanying phenomena well, the forces that were in opposition before Covid-19 won the next elections. A rather striking example in this regard is the 2020 presidential election in the United States, where the poor epidemiological situation in the country affected the fall in Donald Trump’s popularity and contributed to Joe Biden’s victory. If we extend this hypothesis to Latin America and the 2020-2022 elections, we see that in Chile, Peru, Colombia, and Brazil, this statement proved to be fairly true.

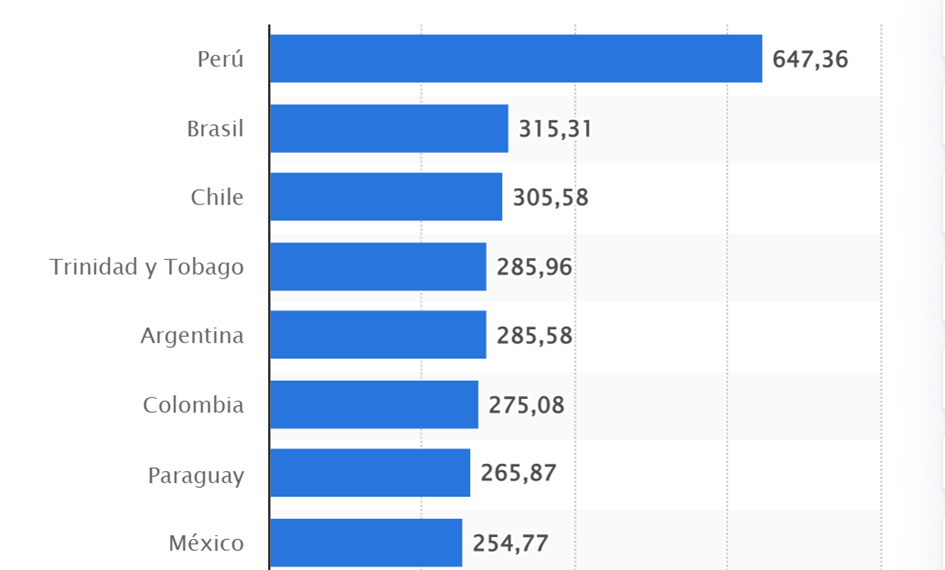

This is especially relevant when it comes to Brazil, where President Bolsonaro has long denied the existence of Covid-19 and failed to take the necessary measures to ensure stability in the country amid the spread of the disease. In Peru, Chile, and Argentina, the dynamics of the coronavirus spread also reached the highest rates in Latin America. Thus, it can be argued that the pandemic, or rather the poor management of the crisis caused by it, was one of the reasons for the second pink tide in Latin America.

We should also highlight the circumstances that contributed to the election of leftist governments in the region under study, but which were dictated by global social trends in the Western Hemisphere. These include the environment, feminism, the “awakening” of indigenous peoples and communities of African descent, and the LGBTI+ rights movement. These four factors gained great social significance in Western societies in the second half of the 2010s. At the same time, the right-wing forces in power in Latin America during this period ignored or were very skeptical of these social problems. Their opponents on the left, on the other hand, actively used the ideas of the need to combat climate change, improve the status of women and representatives of indigenous peoples and communities of African descent.

A triumph of the left? Not so simple as that

An important aspect for understanding the formation of the second pink tide in Latin America is the course of elections in the various countries that fell under this tide. While in Mexico and Argentina in 2018 and 2019 the electoral process was relatively calm, in Chile, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, and Brazil in 2020-2022, the course of events was much more tense, not least because of the aggravation of systemic problems in the region due to the Covid-19 pandemic. When analyzing the electoral process in Chile, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, and Brazil, one should pay attention to three factors:

- Polarization of the elections, i.e. competition between radically different political programs;

- Close results among competitors;

- “Anti-voting” against traditional parties or the emergence of completely new political players.

Even a cursory look at the main candidates in the recent elections in these countries reveals that the main competitors in the second round were almost always representatives of diametrically opposed forces of the extreme right or left. So how deep was the polarization of the recent elections in Latin America?

In Chile, Gabriel Boric, who was described by analysts and journalists as a communist, pitted against Jose Kast, who publicly expressed sympathy for the anti-communist Pinochet regime. In Peru—Keiko Fujimori of the far-right Popular Force party against Pedro Castillo, who is accused of having ties to the communist terrorist organization Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso). In Colombia, Gustavo Petro, who in his youth was a member of the underground communist organization M-19 against the right-wing populist Rodolfo Suárez. In Bolivia, Luis Arce and Carlos Mesa represented political forces that accused each other of usurping power and coup d’état. In Brazil, it was the well-known right-wing populist “Trump of the tropics” Jair Bolsonaro against the leader of the left-wing Workers’ Party, the face of the first pink tide, Luiz Ignacio Lula da Silva.

Throughout the electoral process, all of the above-mentioned candidates were engaged in a fierce struggle for voter sympathy. This was reflected in rather small gaps in the percentage of votes. For example, in Peru, the gap between the presidential candidates in the second round of elections was about 0.25% or 44,000 votes. In Colombia, the gap was 3%, and in the first round of the presidential election in Brazil, it was 5% (the second round will be held on October 30, 2022). Chile and Bolivia are out of this group of countries, where the winners had a considerable lead over their opponents.

Now, what about “anti-voting” against traditional political forces? In three of the five elections in Latin America held in 2020-2022, “new faces” won. This is the case of Gabriel Boric in Chile, who became the youngest president in the country’s history by leading the “I Approve Dignity” movement that emerged on the eve of the election. This cohort also includes Pedro Castillo, who was a teacher and trade union activist until 2017 and became president of Peru in 2021. In Colombia, Gustavo Petro became the first president in the country’s history to come from a left-wing political force, although the 2022 elections were his third. Brazil is not on this list, as both candidates in the second round have previously served as presidents of the country. Similarly, Bolivia does not qualify for this factor, as in 2020, the country’s elections were contested by the former president and the former Minister of Economy.

Given the polarization of the elections, the closeness of the results, and the anti-voting against traditional political forces in the 2020-2022 elections in Latin America, the following interim conclusion can be drawn. First, at least 2 of the 3 factors listed above apply to most of the elections held in this region in the post-Covid era. It should be emphasized that in Mexico and Argentina, elections were held before the pandemic, as well as before the intensification of environmental issues, feminism, and indigenous rights. That is, the elections in these countries were held “under normal conditions,” without major crises that later influenced the course of elections in other Latin American countries.

The second and most important conclusion is that the factors of polarization, the voting closeness and the phenomenon of anti-voting demonstrate a strong public demand for fundamental change, and not that Latin Americans are massively drawn to left-wing political forces. The victory of left-wing politicians in many countries is more likely the result of bad years for their right-wing counterparts, as well as the pandemic and the impact of global social trends. And here it is worth mentioning the example of Ecuador, which falls out of the second pink tide, but has all the same socio-political phenomena that characterize countries where left-wing forces have won. Let’s check it out together.

In the 2021 presidential election in Ecuador, the victory was secured by Guillermo Lasso, who put an end to the whole “dynasty” of leftist Correist presidents who had been in power since 2007.

The victory of Lasso, who is a right-wing politician, is a very clear example of anti-voting in a polarized election. The newly elected president of Ecuador has proposed to abolish all the socio-economic policies that had been built up over almost 15 years before him. It is also worth noting that Lasso was virtually out of power before the 2021 elections.

In turn, his competitor in the second round of elections, Andrés Arauz, advocated the preservation of the Correismo policy, which is also described as “socialism in the twenty-first century”. Thus, in Ecuador, we have both an example of anti-voting against the dominant political forces and polarization of elections. But in the unique Ecuadorian context, the candidate from the right-wing political force won, which once again demonstrates the desire for change and reform among the Latin American population, rather than widespread sympathy for leftist movements.

Be that as it may, the reality is that most countries on the Latin American continent are ruled by leftist forces. Under such circumstances, the question arises as to whether we can really consider this situation a manifestation of the systemic growth of the popularity of leftist political forces in Latin America and their potentially long stay in power. To answer this question, we will have to compare the representatives of the second pink tide with each other, as well as to compare the first and second pink tides.

Analyzing the personalities of the second pink tide

To create a comprehensive picture of the leaders of the second pink tide, one needs to compare their views on foreign policy, the economy, and their attitudes toward critical social issues such as the environment, crime and drug trafficking, women’s rights, LGBTI+ rights, indigenous peoples, and communities of African descent. Thus, let’s introduce all the characters: Mexican Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO for short), Colombian Gustavo Petro, Bolivian Luis Arce, Chilean Gabriel Boric, Argentine Alberto Fernández, Brazilian Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (Lula for short). This comparison does not include Peru, as Pedro Castillo, who won the 2021 elections, has been suspended from the presidency since December 2022. He was replaced by Dina Boluarte, who previously served as Peru’s vice president from the same political force as Castillo. The problem is that this country is currently in a protracted political crisis, and therefore there is no certainty that Free Peru, the left-wing political party that both Castillo and Boluarte represented, will remain in power for long. Returning to the topic of comparing the leaders of the second pink tide, take a look at the following table:

| State and its leader | Foreign policy | Economics and ecology | Crime, drug trafficking | Women’s and LGBTI+ rights | Rights of indigenous peoples and African descent communities |

| Mexico AMLO | Criticism of the United States, support for Cuba and Venezuela, lenient attitude toward Nicaragua, soft stance toward Russia | Disregard for environmental issues, investments in the oil industry. Nationalization measures in the electricity sector | Criticism of the war on drug trafficking, a tendency to ignore the problem | Neglect of the rights of women and the LGBTI+ community | Superficial care for indigenous peoples, general neglect of this issue |

| Colombia Petro | Relatively good relations with the United States, support for Cuba and Venezuela, a soft attitude toward Nicaragua, and a restrained position toward Russia | Significant attention to the environment. A desire to restructure the economy and reduce its dependence on resources. Statements about the need to abandon oil | The desire to change tactics in the fight against drug trafficking, curtailing military operations in this area | Strong focus on the rights of women and the LGBTI+ community | Significant attention to the problems of indigenous peoples and African descent communities |

| Bolivia Arce | Criticism of the United States, support for Cuba and Venezuela, soft attitude towards Nicaragua, very soft stance towards Russia | Relatively high attention to environmental issues. Development of the raw materials sector | Criticism of the war on drug trafficking, a tendency to ignore the problem | Relatively significant attention to the rights of women and the LGBTI+ community | Significant attention to the problems of indigenous peoples and African descent communities |

| Chile Boric | Good relations with the U.S., condemnation of Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua, condemnation of Russia | Significant attention to environmental issues, work on a green transition, reducing dependence on resource exports | The desire to change tactics in the fight against drug trafficking, curtailing military operations in this area | Strong focus on the rights of women and the LGBTI+ community | Significant attention to the problems of indigenous peoples and African descent communities |

| Argentina Fernandez | Neutral relations with the United States, support for Venezuela, Cuba and Nicaragua, soft stance towards Russia | Relatively high attention to environmental issues. Centrist economic policy | Criticizing the war on drugs, discussing the legalization of marijuana | Strong focus on the rights of women and the LGBTI+ community | Superficial care for indigenous peoples, general neglect of this issue |

| Brazil Lula | Criticism of the United States, support for Cuba and Venezuela, soft attitude towards Nicaragua, very soft stance towards Russia | On the one hand, significant attention to environmental issues, especially the preservation of the Amazon rainforest. On the other hand, government support for oil production and the development of agricultural exports | The desire to change tactics in the fight against drug trafficking, curtailing military operations in this area | Strong focus on the rights of women and the LGBTI+ community | Significant attention to the problems of indigenous peoples and African descent communities |

If we examine the table above, we find that the representatives of the second pink tide are sometimes quite divergent from each other. The most striking example would be a comparison of Gabriel Boric and Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), who differ from each other in virtually all respects. Even if we are talking about politicians who are more similar to each other, we will often find some disagreements between them on at least 1-2 of the above criteria. This comparison allows us to conclude that, in fact, on each of the important social, economic, or political issues, the second pink tide is divided roughly in half, and therefore we can hardly expect much unity in policy making from its representatives. This conclusion brings us to a comparison of the first and second pink tides.

The first pink tide vs. the second pink tide

The pink tide of the 2000s was much more unified in its views on socio-political issues. At least because there were fewer controversial issues than there are now. In the 2000s, questions of gender, LGBTI+ rights, indigenous peoples, and communities of African descent were either on the margins of public discourse or were not as pressing as they are now. In terms of foreign policy, the United States was seen as an “evil empire” after the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, and Russia had not yet invaded Georgia. In addition, the Cold War ended not so long ago, and many of the leaders of the first pink tide (Chávez, Morales) were thinking in terms of it. Therefore, the Latin American leaders of the 2000s had much less cause for controversy than their successors do today.

Another considerable success factor for the first pink tide was the mono-majority of pro-government parties in parliaments, which guaranteed easy adoption of any decisions. In the case of the second pink tide, left-wing presidents have either a very active opposition and very shaky coalition alliances, or even opposition dominance in the legislature. One of the best symbols of this is the failure to vote on a new constitution in Chile this year. Although President Gabriel Boric has a solid approval rating, and the demand for a new constitution is one of the most popular in Chile, the opposition was able to convince the population that the draft document presented by the presidential political force was not worthy of support.

Another interesting observation should be noted. The years of birth of the leaders of the second pink tide practically coincide with the years of birth of politicians of the first pink tide, which took place almost 20 years ago. Chávez was born in 1954, AMLO—in 1953. Rafael Correa—in 1963, Luis Arce—in 1963. The only exception to this rule is Gabriel Boric, born in 1986. This, in turn, does not suggest a change in the generations of politicians, but rather that the representatives of the leftist movement have simply grown older. And while in the 2000s the pink tide looked like a cluster of active 40- to 50-year-old leaders, in the 2020s it is a competition between 60- to 70-year-olds. This factor, in turn, calls into question the duration of the second pink tide simply because of potential health problems of its representatives. It is highly likely that in the next elections in Latin America, which will take place in 4-5 years, the leftist movements will be represented by other politicians, for whom it will be a separate challenge to take advantage of the personal political capital and authority that the current presidents will leave behind.

To this we add the complexity of the international situation, which is characterized by the second pink tide: the Russian-Ukrainian war, record inflation, rising energy prices, and the confrontation between the United States and China. On top of all this is the social polarization observed in Latin American countries, which suggests that the population as a whole was ready for the blue tide of right-wing politicians. Therefore, all of the above factors pose a significant number of challenges to the representatives of the second pink tide that their predecessors from the first one did not have. That is why the fate of the political landscape of the entire continent depends on how successful their presidency will be. It seems very likely that we will see the fragmentation of political forces and the transformation of Latin America into a blue and pink mosaic, rather than the crystallization of the pink tide and its continuation throughout the 2020s.

The second pink tide and Russian aggression against Ukraine

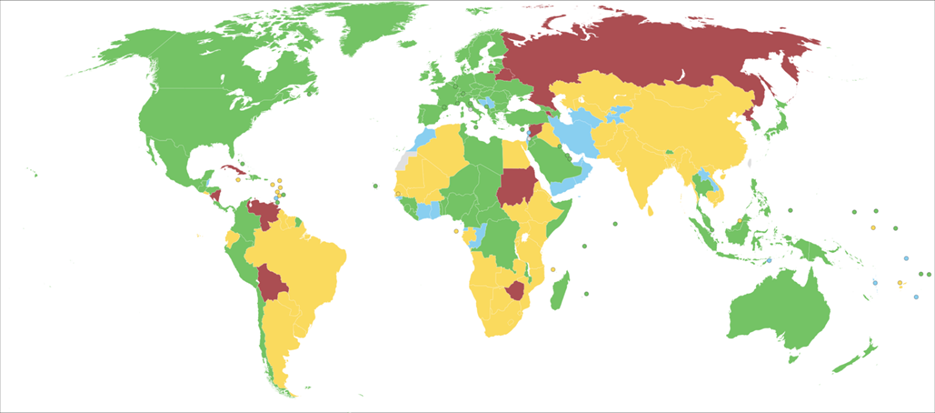

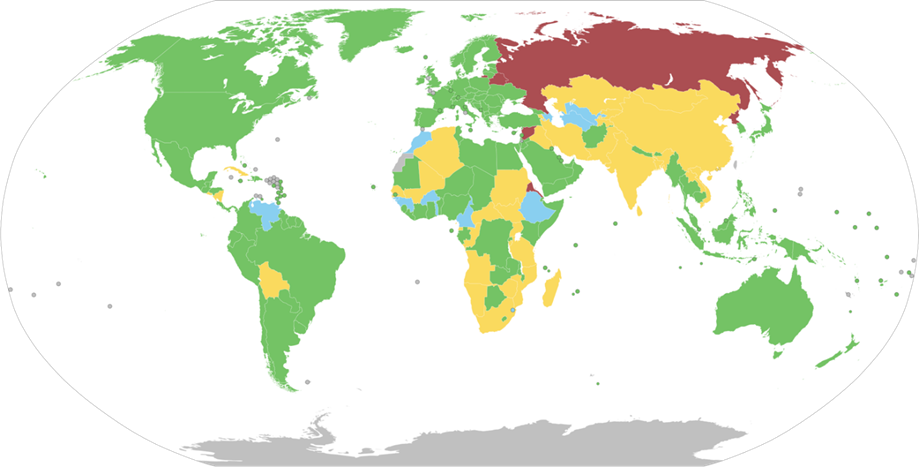

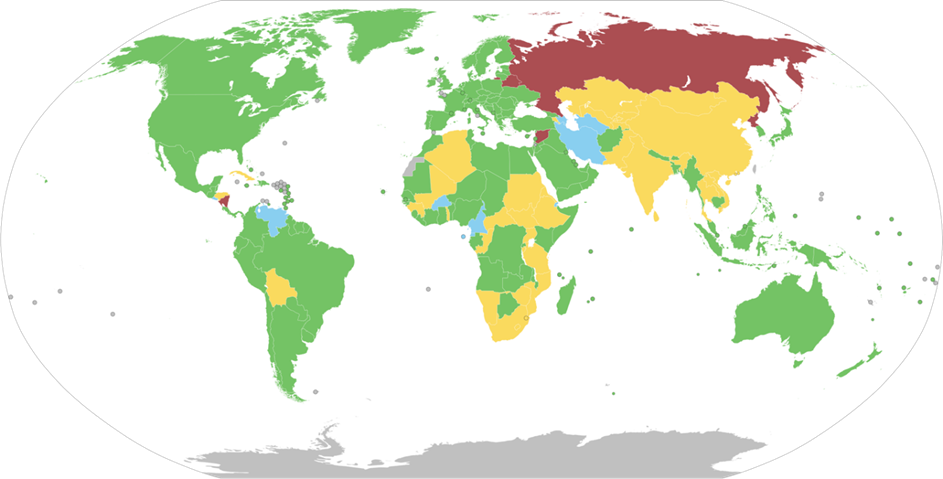

Within this regard, what interests us is how Latin American countries reacted to the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion of our country and what is the attitude of these leftist governments to the war. One of the best indicators of this is the voting in the UN for General Assembly resolutions regarding Ukraine. Let’s take a look at how the 9 largest Latin American countries (Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Venezuela, Argentina, and Brazil) voted in 2014, March, and October 2022. UN General Assembly resolution on the territorial integrity of Ukraine No. 68/262 of March 27, 2014 (adopted after the occupation of Crimea by the Russian Federation):

Out of the nine largest countries in the region, 4 supported the resolution, 2 voted against it, and 3 abstained. Among those who voted against were Russia’s largest allies in the region—Bolivia and Venezuela. At the time of voting for the resolution (March 2014), the political spectrum in these 9 countries was as follows: 2 countries with right-/ center-right governments, 7 countries with left-/ center-left governments. As we can see, Latin America was at the end of the first pink tide. UN General Assembly Resolution ES-11/1 of March 2, 2022 condemning Russian aggression (adopted a week after the start of the full-scale invasion):

Out of the nine largest countries in the region, 7 supported the resolution, 0 voted against, 1 abstained (Bolivia), and 1 did not vote (Venezuela). At the time of the vote on the resolution (March 2022), the political spectrum in these 9 countries was as follows: 4 countries with right-/ center-right governments, 5 countries with left-/ center-left governments. At that time, Latin American countries were transitioning out of the blue tide and gradually entering the second pink tide. At first glance, it may seem that everything is quite simple: right- and center-right governments support Ukraine, left- and center-left governments do not support Ukraine. However, let’s take a look at a similar vote at the UN in October 2022, when Latin America had already fully entered the second pink tide.

UN General Assembly resolution ES-11/4 of October 12, 2022 (condemning the “referenda” in Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, Donetsk, and Luhansk regions):

The voting pattern for these 9 countries is exactly the same as in March 2022. An important difference, however, is that during this time, the number of left- and center-left governments in Latin America has increased. At the time of the vote on the resolution (October 2022), the political spectrum in these 9 countries looked like this: 2 countries with right/right-of-center governments, 7 countries with left/left-of-center governments. It follows that the governments of the second pink tide diplomatically supported Ukraine at the level of the previous blue tide governments. Therefore, given the voting trends at the UN, the hypothesis “right-wing support, left-wing opposition” seems inappropriate.

But what about other types of support and the general attitude toward Russian aggression? If we are talking about humanitarian or financial support for Ukraine, we must recognize that most Latin American countries are in need of help themselves. The Argentine government will not allocate funds for the reconstruction of Ukraine when annual inflation in our country during the war was about 30% in 2022, and in Argentina it was close to 100%. The rhetoric of “we stand for peace, we must seek a diplomatic solution to the conflict” is heard not only from Latin American but also from European and North American politicians and public figures. Against this backdrop, Brazilian President Lula, who claimed that Volodymyr Zelenskyi was as responsible for the war as Putin, or who offered to cede the territory of Crimea in exchange for a settlement of the conflict, appears on a par with the President of Croatia, who said that Ukraine should not be supported with weapons. Or with the Belgian Foreign Minister, who, being well aware of the European political situation in 2021, visited the temporarily occupied Crimea. The difference is that due to geographical distance and the lack of systematic outreach on the part of Ukraine, Latin American politicians can often express similar opinions due to a banal lack of knowledge of the situation in Eastern Europe and its history.

As for military cooperation with the countries of the region, one should understand that it is the highest level of interaction between countries, and therefore usually develops in the context of an already established political dialogue at the highest level. Therefore, it would be naive to expect Latin American countries, for whom Russian aggression is taking place “somewhere else” and who are not very aware of Eastern Europe (as well as Eastern Europe is of Latin America), to transfer or sell large-scale arms to Ukraine. This, of course, is compounded by strong Russian pressure through diplomacy and propaganda. Indicatively, Colombia will not provide Ukraine with weapons because of the lack of close political dialogue between the countries, which in turn stems from the absence of at least a Ukrainian consulate in that country. A separate important aspect in this matter is the Latin American tradition of neutrality, which all countries in the region have been trying to adhere to since gaining independence. Therefore, in its attempts to obtain arms supplies from the LAC countries, it would not be only Ukraine that would face rhetoric about the need for dialogue instead of real assistance.

As for the rest, we observe a more pro-Ukrainian position in the second pink tide compared to the first one. At the same time, it is not very different from the blue tide of right-wing/centrist governments in the 2010s. It can be assumed that the change in perception of Ukraine during the 2000s-2020s was influenced by both the efforts of Ukrainian diplomacy (for example, the process of recognizing the Holodomor as genocide) and the increasingly aggressive and inadequate policy of the Russian Federation in the international arena. And although the position of Latin American countries may seem insufficiently pro-Ukrainian, compared to African and Asian countries, we find much more support in this region in the UN voting.

Conclusions

After analyzing the second pink tide and the circumstances that contributed to its emergence, what conclusion can we draw? In general, it seems that the term “second pink tide,” although it describes the political process in Latin America, is in fact a very arbitrary term that we use merely for lack of a more apt analog. Cuba, Venezuela, and Nicaragua are examples of a “pink swamp” where no changes have taken place (in Cuba since 1959), and thus they can be attributed to the second tide with great reserve.

The leaders of Mexico, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Argentina, and Brazil seem to belong to ideologically similar left-wing political movements, but in fact differ from each other in many respects, both in foreign and domestic policy. The prospects for close and active cooperation and integration between these countries are doubtful, which contrasts with the era of the 2000s, which gave us a whole bunch of regional Latin American integration projects. The longevity of the second pink tide is also questionable, due to the difficulties that accompany the tenure of its representatives.

So what gave rise to the second pink tide? It is a good coincidence for left-wing parties that the covid pandemic, which has driven Latin American economies into an even greater crisis, and the global intensification of the “left” social agenda (feminism, the LGBTI+ rights movement, and the awakening of indigenous peoples). The example of Ecuador, where a representative of the right-wing movement, Guillermo Lasso, was able to get closer to feminist organizations and LGBTI+ movements, demonstrates that opponents of the left can successfully adapt to modern social challenges. Moreover, the prospects of the pink tide depend solely on how well its representatives will be able to tackle the persistent problems that have existed in Latin America for decades—poverty, property stratification and inequality, corruption, and drug trafficking.

Latin American left- and center-leaning governments are generally neutral with regard to Ukraine. In some states, such as Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, and Bolivia, Russian influence is relatively strong. In other countries, there is a struggle for the “hearts and minds” of citizens and politicians between Ukrainian and Russian narratives about the war. Latin American countries are unlikely to be able to support Ukraine financially or humanitarianly (except for initiatives of the Ukrainian diaspora or individual public figures). Nor should we expect military support, given the insufficient level of political dialogue between Ukraine and the region. In terms of diplomatic backing, our country and its partners have managed to achieve a very high level of support for “Ukrainian resolutions” in the UN from Latin American states.

© Think Tank ADASTRA

Author:

Oleksii Otkydach

The information and views set out in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine.

Think Tank ADASTRA

Phone: +380954592954

E-mail: adastra@adastra.org.ua