PROSPECTS OF THE ISTANBUL AGREEMENTS FOR UNBLOCKING EXPORTS OF UKRAINIAN GRAIN: IMPACT ON GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY AND THE OVERALL INTERNATIONAL SITUATION

Author:

Yevgeniya Gaber

INTRODUCTION

The importance of the Ukrainian agricultural sector and uninterrupted exports of Ukrainian grain to world markets can hardly be overestimated—both for Ukraine’s economy and for global food security.

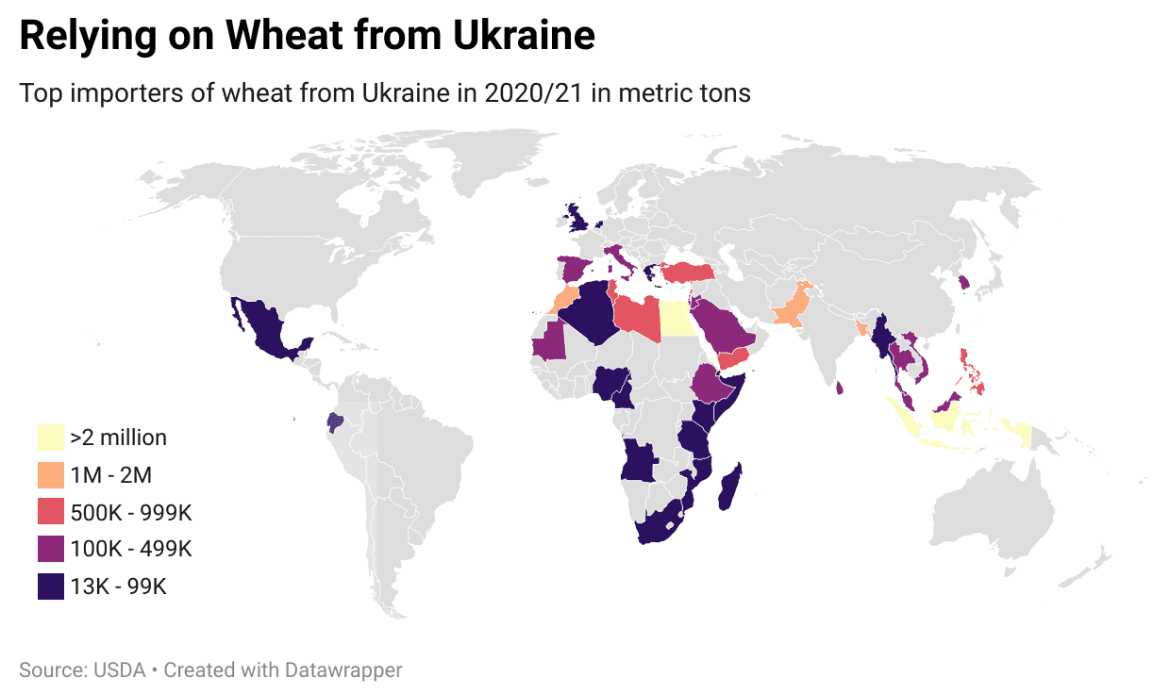

Ukraine produces a sizable part of the world’s food: about 27% of sunflower seeds, 5% of barley, 3% of wheat and rapeseed, 2% of corn. Meanwhile, its role in the world food trade is much more important.

Ukraine ranks 1st in terms of world exports of sunflower oil with a share of 46% (the main markets are India, the EU, China); 3rd in terms of barley exports—17% (China, Türkiye, Saudi Arabia) and rapeseed—20% (EU, Pakistan, the United Kingdom); 4th place by the share of corn exports—12% (China, EU, Egypt, Iran, Türkiye) and 5th place by wheat exports—9% (Egypt, Indonesia, Türkiye, Pakistan, Bangladesh).

Table 1. Ukraine’s share in world agrarian exports (2021)

| Sunflower oil | Corn | Wheat | Rapeseed | Barley | |

| Total exports | $6.4 bln | $5.9 bln | $5.1 bln | $1.7 bln | $1.3 bln |

| Volumes | 4 950 000 t | 23 000 000 t | 19 000 000 t | 2 700 000 t | 5 800 000 t |

| Percentage in world exports | 46% | 12% | 9% | 20% | 17% |

| Place among the world exporters | 1 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Main markets | India, EU, China | China, EU, Egypt, Iran, Türkiye | Egypt, Indonesia, Türkiye, Pakistan, Bangladesh | EU, Pakistan, United Kingdom | China, Türkiye, Saudi Arabia |

The situation is complicated by the fact that many countries of the world remain highly dependent on imports of these types of agricultural products, primarily the countries of the Global South—Africa, the Middle East and Southeast Asia. Given Ukraine’s share in the world market, even the increase in production in other countries and the restructuring of logistics chains are not able to compensate for the loss of supplies from Ukraine.

In addition, the World Food Program, which is a humanitarian initiative of the UN to provide food aid to the poorest countries in the world, receives about 40% of wheat from Ukraine. For some countries, such as Egypt, Yemen or Bangladesh, the supply of Ukrainian grain is a guarantee of basic survival. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, a record 276 million people are currently on the verge of famine, including almost 49 million people in 43 countries in extreme hardship.

Failure to fully unblock exports of grain and other agricultural products from Ukraine leads to worsening hunger for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable people and poses a threat to national security for many developing countries. The most challenging situation remains in Africa, in particular, South Sudan and Somalia, where the price of wheat has increased by more than 45% since the beginning of the war, according to the African Development Bank.

Given that before the full-scale Russian invasion, Ukraine exported more than 90% of its grain, fertilizers and agricultural products through the Black Sea ports of “Greater Odesa” (Odesa, Chornomorsk, Pivdennyi), Mykolaiv and Kherson, as well as the ports of the Sea of Azov, unblocking sea routes remains a key condition for the restoration of normal functioning of world markets. As David Beasley, Executive Director of the World Food Programme, stated during the UN Security Council debate, “Failure to open the ports will be a declaration of war on global food security, resulting in famine destabilization of nations, as well as mass migration by necessity”.

This is precisely what the aggressor state is trying to achieve by blocking sea trade routes—economic exhaustion of Ukraine, incitement of popular protests and simultaneous destabilization of many regions of the world, as well as creation of additional pressure on Ukraine’s Western partners by artificially creating food and migration crises.

What has the Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI) achieved?

On July 22, 2022, with the signing of agreements between representatives of Türkiye, the UN and Ukraine, on the one hand, and a mirror document with Russia, on the other hand, the Black Sea Grain Initiative mechanism was introduced. On August 1, the Joint Coordination Centre (JCC) started its work in Istanbul.

The agreement on the opening of three ports of the “Greater Odesa”, through which more than half of Ukrainian grain exports are carried out, was perceived by many in the world as a breakthrough in overcoming the problem of hunger and food crisis. “The UN-led Initiative has helped to stabilize and subsequently lower global food prices and move precious grain from one of the world’s breadbaskets to the tables of those in need. Due to the initiative, port activity in Ukraine is picking up, and large shipments of grain are reaching world markets”, the UNCTAD report says.

Indeed, the Food Price Index published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations showed that since the start of the grain corridor, prices for staple foods in the world have declined by about 8.6% in July, 1.9% in August and 1.1% in September. However, in November, following the crisis artificially created by the Russian side with the suspension of its participation in the JCC, wheat and corn prices rose sharply again. Additionally, the instability of the corridor operation and uncertainty about the future of the BSGI itself, as well as the precarious security situation in the region and the presence of floating mines in the Black Sea basin further raise logistics and insurance expenses.

How much grain was exported and where did it go?

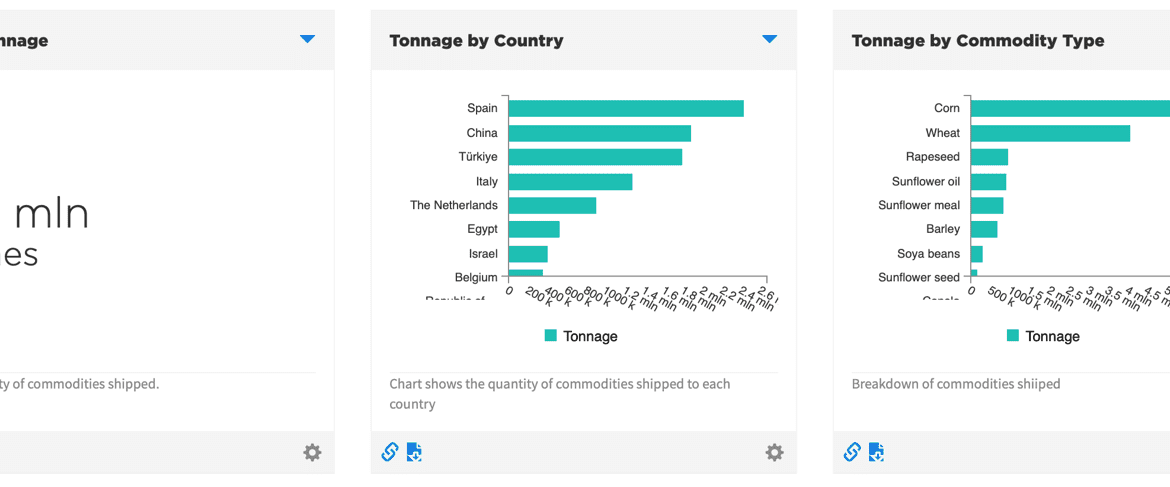

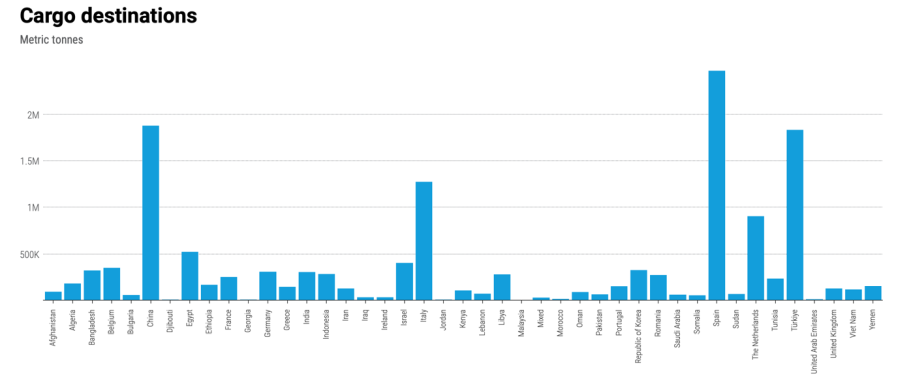

As of December 2022, more than 14 million tons of grain were exported within the grain corridor, of which: 43%—corn, 29%—wheat, 7% rape, 6%—sunflower oil, 15%—other agricultural products.

The main destination countries were Spain (2.5 million tons), China (1.9 million), Türkiye (1.8 million tons), Italy (1.3 million tons), the Netherlands (almost 900 thousand tons). In many cases, these countries are not final consumers, and they re-export Ukrainian wheat in the form of grain or after processing.

Among the main achievements of the Grain Initiative, the UN Secretariat usually notes several factors:

- Resumption of Ukrainian grain supplies to world markets, which significantly alleviated the food crisis;

- Unblocking Ukrainian ports, and thus supporting Ukrainian farmers, agribusiness and the Ukrainian economy in general;

- Providing food to the poorest countries in the world, as about a quarter of the cargo is sent to low- and lower-middle-income countries: Egypt, India, Iran, Bangladesh, Kenya, Sudan, Lebanon, Yemen, Somalia, Djibouti, Tunisia;

- Falling world grain prices, reducing pressure on world markets and mitigating food inflation;

- Setting up a platform for cooperation between Ukrainian and Russian delegations, which is necessary to continue diplomatic efforts to resolve the Russian-Ukrainian conflict.

In Türkiye, where the Grain Initiative is considered to be the main diplomatic success of the country’s leadership and has become a factor in strengthening Ankara’s regional role, the agreement between Ukraine and Russia brokered by Ankara is seen as a prototype of a negotiation model for further full-scale peace. Defense Minister Hulusi Akar, who coordinates the work of the JCC from Türkiye, has repeatedly stated that he regards the grain corridor not only as a transport artery, but also as a “road to peace”. Therefore, it is not only about the supply of grain, but also about the development of mechanisms to restore confidence between the warring parties. According to Turkish diplomats, the grain deal should be the first step towards a ceasefire and peace with Russia, while the Joint Coordination Centre is a potential platform for negotiations.

At the same time, most Ukrainian experts have been pointing out from the outset that the Grain Initiative is a forced, temporary and limited step that should be viewed only as a technical arrangement to partially unblock Ukrainian ports if the issue cannot be resolved militarily. The Grain Initiative itself is an unsubstantiated political arrangement rather than a full-fledged international accord. There are no prospects for expanding it to a diplomatic dialogue between the parties, while the military, operational, insurance and geopolitical risks heavily outweigh the modest achievements in improving the food security situation.

Why is the success of the Istanbul agreements limited and what problems remain unresolved?

- The Russian regime has repeatedly proved its contempt for international law and any agreements, including the grain initiative. Although the Black Sea Grain Initiative provides for “non-attack on commercial and other civilian vessels and port infrastructure that are part of the Initiative”, the day after the signing of the agreement, the port of Odesa came under rocket fire from Russia. Similarly, the southern regions of Ukraine are regularly attacked from the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, resulting in damage to port facilities and port infrastructure. Furthermore, even before the expiry of the first 120-day period of the BSGI, Russia suspended its participation in the Joint Coordination Centre under false pretenses, thus jeopardizing the implementation of the agreements. There is no doubt that the Kremlin will continue to use the BSGI as a mechanism of blackmail and pressure on Ukraine and its international partners, resort to provocations to destabilize the situation, increase prices for food and related services.

- Unpredictability, instability and lack of security guarantees make logistics, insurance and chartering of ships much more expensive. According to Andrii Vadaturskyi, CEO of one of the leading Ukrainian agricultural companies, while before the war the cost of logistics was between $4 and $15 per ton, now it is approximately $120–150 per ton. This places an additional financial burden on Ukrainian farmers and makes grain production and exports unprofitable.

- High security risks make major players in the transportation market refuse to enter the Black Sea ports. Currently, the majority of ships carrying grain through the humanitarian corridor belong to small companies, not market leaders. The number of ships flying the Turkish flag has grown noticeably. In November, Putin remarked that if Russia withdraws from the Initiative again, it “in any case will not impede the supply of grain from the territory of Ukraine to the Republic of Türkiye, bearing in mind Türkiye’s neutrality in the conflict in general, and the capabilities of the grain processing industry of Türkiye, and the efforts of President Erdogan aimed at ensuring the interests of the poorest countries”. It can be assumed that guarantees of grain supplies from Ukraine by the Turkish fleet even in case of disruption of humanitarian corridors were one of the important conditions of the agreements between official Ankara and Moscow.

- Uncertainty is added by the short, 120-day extension of the Initiative, which allows Russia to constantly hold the whole world hostage. Having unilaterally “left” the Initiative ahead of schedule, the Russian side has already demonstrated that it is not going to comply with its obligations under the BSGI, so Moscow’s next demarche is only a matter of time and the positions of other participants.

- The main problem in the implementation of the Initiative remains, in fact, ensuring the smooth functioning of the humanitarian corridor itself, which is now blocked by the Russian side. Since mid-September, Russian representatives in the JCC have been delaying the authorization of vessels in both directions (entering and leaving Ukrainian ports) under fabricated pretexts, creating additional hurdles during the inspection of vessels and impeding normal maritime traffic, complicating traffic through the Straits and threatening an environmental disaster to the 16 million metropolis. According to the Monitoring Group of the Institute for Black Sea Strategic Studies, in October-November, the average waiting time for the inspection of the “grain fleet” vessels in the Sea of Marmara increased five times, reaching in some cases more than twenty days. In early December, the number of ships awaiting inspection reached hundreds, and 2-3 vessels per day received permission to pass. For comparison, in the absence of Russian representatives in the JCC from October 31 to November 1, inspectors of the UN Secretariat and the Turkish delegation conducted 46 and 36 inspections respectively. This proves the fact that the grain agreements should be considered only in a broader political context, and the viability of the JCC mechanisms and the entire Initiative depends solely on the will of Russia, “an arsonist acting as the firefighter”. All this makes the Initiative a shaky mechanism that does not solve the essence of the problem, but only addresses its consequences, and yet—with extremely limited efficiency.

- Finally, the unblocking of grain exports is only one, small part of a much larger and complex problem faced by the Ukrainian agricultural sector as a result of Russian aggression. At the beginning of active hostilities, about 30% of organic producers in Ukraine announced a complete suspension of operations, another third—a partial suspension. At the beginning of December, about 1/5 of all agricultural land remained under occupation, direct losses from Russian aggression for the agricultural sector amounted to about $6.6 billion, indirect ones—more than $36 billion.

Russia’s deliberate destruction of Ukraine’s agricultural, transport, port and energy infrastructure, seizure of land and destruction of farms in the occupied territories, ruining of agricultural machinery, mining and rocket attacks on thousands of hectares of fertile land, inability to harvest and conduct a new sowing campaign, destruction of granaries, massive export of stolen Ukrainian grain from the occupied territories, redistribution of world markets and logistics chains, outflow of human capital and financial difficulties, continued blocking of access to Mykolaiv, Kherson and ports of the Sea of Azov—all this demonstrates the limited positive impact of the grain initiative and its inability to solve key problems of restoring full production and export of Ukrainian grain.

Besides, Russia’s use of the Istanbul agreements as an instrument of pressure on world markets, Ukraine and its international partners carries additional risks, which should be discussed separately.

What are the risks of the implementation of the grain agreements for Ukraine and the world?

Russia has repeatedly used the BSGI platform to voice its demands to expand exports of its own (and stolen Ukrainian) grain to international markets. There is no doubt that this pressure will only intensify in the future. It should also be expected that against the backdrop of the deteriorating humanitarian situation, the Russian side will be supported in these calls by the UN and Türkiye. President Erdogan has repeatedly reminded of the West’s failure to honor its obligations to Russia and stressed the need to create conditions for the export of Russian grain and fertilizers to world markets.

In addition to the mediating role that Türkiye is trying to play between Ukraine and Russia, Ankara’s interest in restoring full trade with Russia is explained by quite pragmatic interests. According to UN estimates, Türkiye provides about 22% of annual grain imports from Russia and only 3%—from Ukraine. The country has a well-developed processing industry: Türkiye ranks first in the world in flour exports and second in pasta exports, while it imports most of its wheat from Russia (67%) and Ukraine (21%).

Currently, Türkiye is confidently among the top three countries of destination for Ukrainian grain under the Grain Initiative. Expanding supplies of cereals and oilseeds from Russia will automatically mean greater involvement of Türkiye in international logistics chains and trade in agricultural products.

- Although direct sanctions against Russian food have never been imposed, the export of Russian grain is complicated by problems with the relevant settlements and banking operations. Hence, Russia demands exemptions from sanctions for a number of state-owned banks to make payments for the export of Russian grain and fertilizers under the Grain Initiative. In particular, these are the state agricultural lenders—Rosselkhozbank, Roseximbank and others. This creates a threat that the erosion of the sanctions regime will continue, gradually spreading to other sanctioned banks and operations to meet “humanitarian needs” within or outside the grain deal.

- Another problem that Russia is trying to solve through the Grain Initiative is the facilitation of the chartering of ships, insurance and access to European ports. In a recent interview, Turkish presidential spokesman Ibrahim Kalin declared that Russia rightly demands to resolve the issues that will unblock the export of Russian grain, fertilizers and ammonia to world markets. To this end, Türkiye called on the United States to provide American and European insurers and logistics companies with guarantees that they will not fall under secondary sanctions in case of cooperation with Russia.

In turn, according to The Wall Street Journal, during the elaboration of the ninth package of sanctions against Russia, UN representatives put pressure on the EU to facilitate Russian exports of food and fertilizers in accordance with the agreement with the Kremlin, which was formalized by an additional memorandum with Antonio Guterres under the Istanbul accords. In particular, it refers to the lifting of “logistics sanctions”, ensuring free access to European ports for ships with Russian fertilizers and food products, as well as unblocking the assets of individuals and legal entities (including oligarchs), where necessary for the supply of fertilizers. In order to avoid circumvention of the sanctions, the exemptions will apply only to large Russian agribusinesses that operated in this sector before the sanctions were imposed. In addition, the supplies must be part of the UN Food Programme or be directed to developing countries covered by the UN priority food security order.

At the same time, it is still unclear how to determine which Russian business will be exempted from sanctions; which countries are considered priority destinations, and how to make sure that the final destination corresponds to what is declared in the documents. All this creates preconditions for bypassing sanctions, corruption schemes, shadow mechanisms and undermining of the previously introduced sanctions regime. Additional threats from the legal and political points of view are the non-public nature of the agreements between Russia and the UN (the text of the memorandum with the UN Secretary General is not publicly available on the UN website), the misinterpretation of the essence of the agreements reached by all parties to the negotiations and numerous misunderstandings that arise in the process of implementing the agreements between Ukraine and its Western partners—the EU, the U.S., Türkiye and the UN, all of which are trying to fulfill Russia’s demands in their own way.

- The key issue remains the agreement to unblock the export of ammonia and Russian fertilizer exports, which are considered by Türkiye and the UN as a necessary step to mitigate the food crisis.

Before the war, Russia’s share in the global ammonia market was 20%. About half of these volumes were transported to Ukraine’s Pivdennyi port through the Togliatti-Odesa ammonia pipeline from the production facilities of TogliattiAzot, which belongs to Dmitry Mazepin’s Uralchem group. The transit of ammonia stopped on February 24, and in mid-October the owner of the company was included in the new Ukrainian sanctions package. Among the restrictions imposed on the businessman by the Ukrainian authorities is “partial or complete cessation of transit of resources”.

Experts stress that ammonia exports are another direct way for Russia to circumvent European sanctions. In fact, the main raw material for ammonia production is natural gas, and the Russian chemical industry is actually a branch of Gazprom. Thus, nitrogen and phosphate enterprises of the Russian chemical industry are part of the chain of production and sale of Russian natural gas. “With the reduction of gas export supplies, ammonia is the simplest and most logical product for utilization of excessive volumes of natural gas. Limiting Russian gas exports and increasing ammonia exports is like transferring money from one pocket to another”, specialists say. If the ammonia pipeline is restored, it will not only replenish the Russian budget by $200 million per month, but will also turn into a chemical weapon of delayed action, in view of Russia’s regular missile attacks on southern Ukraine.

After unsuccessful attempts by the UN and official Ankara to negotiate with Kyiv on the resumption of ammonia transit through the Togliatti-Odesa pipeline, the Financial Times reports that the parties managed to reach an agreement to unblock ammonia exports from Russia through traders from third countries. Thus, in an interview with the FT, Dmitry Mazepin stated that an American or other “non-Russian” company, selected among the largest international traders, will buy ammonia from Russia and transport it through the territory of Ukraine to the port of Odesa, from where it will be transported across the Black Sea to other countries. According to him, exports can start immediately, and approximately 80% of the production will be directed to African countries. In fact, this means that Russia has achieved the satisfaction of all its requirements.

- A separate issue is the list of countries to which grain and fertilizers should be exported through the grain corridor. Before the war, the largest importers of Ukrainian wheat were Egypt, Indonesia and Bangladesh. In September, the UN reported that just under 30% of the wheat went to low-income countries, while 44% went to high-income countries. According to Amir Abdulla, the official Initiative coordinator for the UN Secretariat, Türkiye is one of the key countries receiving Ukrainian grain, although “actually, much of the food that came to Türkiye is probably going to be processed and shipped to parts of Africa and other parts of Asia”. At the beginning of December, according to the statistics of the Joint Coordination Centre, the bulk of Ukrainian grain exported within the framework of the grain corridor was sent to Spain, Türkiye, China, Italy and the Netherlands.

In these circumstances, there are more and more appeals from Russia to define a list of “needy” countries to which grain should be delivered as a priority. Putin even offered the Turkish President to send grain to poor countries in Africa “for free”. The intention to help the population of Djibouti, Somalia and Sudan was supported by President Erdogan. The obvious risks associated with this for Ukraine are the legitimization of Russia’s illegal trade in stolen Ukrainian grain and the need to form grain caravans in accordance with Russian criteria, and not in accordance with previously concluded market contracts.

At the same time, the issue is not only about periodic demands of the Russian side to change the provisions of the grain agreement, but also about serious image losses for Ukraine. Thus, in the light of the Kremlin’s anti-Western and anti-Ukrainian propaganda, Ukraine appears in the countries of the Global South and in Türkiye as a country that “profits” from the food crisis, trading with rich Europeans and deepening food shortages due to sanctions, while Russia “helps poor countries in Africa”.

The launch by Ukraine of the humanitarian initiative Grain from Ukraine, which is implemented in partnership with the UN World Food Programme, has helped to rectify the situation. In particular, the program envisages that Ukraine will send part of the wheat for export to those African countries where the problems of hunger are most acute. Part of the exported grain can be purchased by the states participating in the project. Currently, the total amount of pledged contributions from the program participants is almost $190 million. At the same time, the rhetoric of the Russian and Turkish leadership emphasizes the ignoring by the West and Ukraine of the interests of developing countries and the failure to deliver on the promises made to Russia within the framework of the “package agreements” of the Black Sea Initiative.

- The problem of stolen Ukrainian grain, which Russia continues to export hundreds of thousands of tons from the occupied territories of Ukraine and present as its own, resorting to falsification of documents, multilevel shadow schemes and outright violations of international maritime law, has not been resolved yet.

- Finally, the core problem from the point of view of international law is setting a dangerous precedent, which Turkish researcher Yörük Işık has aptly called “Russia’s veto over freedom of navigation in the Black Sea”. While the Black Sea agreements have partially restored access of Ukrainian grain to world markets, they fail to address the critical issue at the heart of the current problems. In fact, Russia now has full control over who enters and who leaves the Black Sea basin, which is a violation of the basic concept of the law of the sea regarding freedom of navigation. “The grain deal may be safe today, but it risks normalizing Russia’s blatant violation of international law in the Black Sea. Under the current arrangement, which Kyiv and Moscow each signed with the United Nations but notably not with one another, Russia is permitted to inspect international vessels of sovereign nations traveling to and from Ukraine’s Black Sea ports. Even though Ankara had helped to mediate this outcome, it is an outrageous situation that should not be acceptable to Türkiye”, the expert notes.

In fact, the cause of all the current food, raw materials and humanitarian crises in Africa, the Middle East and the Global South is Russian aggression, and a sustainable solution can be found only when Russia ends its illegal blockade of Ukrainian ports. Instead, violating international law to meet the demands of the country that first breached these norms will lead to dangerous consequences. Russia’s “creeping occupation” of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov not only calls into question the future application of the 1936 Montreux Convention, but could also set a dangerous precedent for abuses of international law in other parts of the world, from the Baltic Sea to the Indo-Pacific.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The functioning of the grain corridor under the Black Sea Grain Initiative is only a small part of a much larger and more complex problem. The central issue remains the lifting of Russia’s illegal blockade of Ukrainian ports, which should ensure the restoration of maritime traffic and normal trade between Ukraine and the world. This, and not the grain deal itself, will make the greatest contribution to the solution of the global food crisis. And this is what the main diplomatic efforts of Ukraine and its international partners, first of all the EU and NATO, should be aimed at.

In its current form, the performance of the agreements corresponds primarily to the interests of Russia and Türkiye, but not to Ukraine, the countries of the Global South or the international community, as it de facto legitimizes the Russian naval blockade, illegal trade in stolen Ukrainian grain, circumvention of European sanctions, as well as facilitates the return of major Russian banks to the international SWIFT system and replenishment of the Russian budget with revenues from the export of Russian ammonia (in fact—natural gas), fertilizers and other related commercial activities.

Russia has never had any intention of seriously fulfilling its obligations under the Istanbul agreements, but instead used these negotiations as a blackmail tactic and a way to divert attention from its military aggression on land and at sea. There is no doubt that Russia will continue to create new crises to impede the work of the existing corridor, block the expansion of the Initiative to other Ukrainian ports (Mykolaiv, potentially Kherson) and to maximize its benefits.

Türkiye considers the Black Sea Grain Initiative as an opportunity to strengthen its role in the Global South and in relations with the West, to enhance its position in the world markets and in new logistics chains, to demonstrate the benefits of the policy of neutrality in the Russian-Ukrainian war, while maintaining relations with both countries, and not to join the sanctions against the aggressor country, arguing that it is necessary to preserve the Istanbul platform for negotiations.

Under these conditions, Ukraine should insist on the unacceptability of Russia’s gross violations of the norms and principles of international law, including the law of the sea, and work on a sustainable and long-term solution to the problem of de-occupation of the Black Sea.

In the short term, the functioning of the grain corridor and participation in the work of the Joint Coordination Centre should provide support to the agricultural sector of Ukraine and continue the export of Ukrainian grain to world markets. In parallel, it is necessary to continue working on the development of alternative logistics routes (including the development of the potential of the river fleet and land transportation).

At the same time, the weakening of Russia’s military positions in the region as a result of a number of successful operations of the Armed Forces of Ukraine should be a reason to step up negotiations with partners on 1) increasing pressure on Russia to restore the full-fledged work of the JCC and inspection teams; 2) inclusion of Mykolaiv and other Ukrainian ports in the work of the grain corridor; 3) continuation of the work of the JCC in the trilateral format Ukraine-Türkiye-UN in case of new provocations by Russia (a format that has already proved its effectiveness); 4) ensuring escort of the “grain fleet” by NATO warships (in particular, Romania and Türkiye in case Ankara applies the provisions of the Montreux Convention to close the Straits to warships of non-Black Sea countries).

NATO should reinforce its naval presence in the Black Sea to protect freedom of navigation. Through unblocking Ukrainian ports and deterring Russian aggression at sea, the Alliance could tackle a threefold issue: 1) to support Ukraine in its just war for independence and order based on international law; 2) to defend freedom of navigation in the Black Sea and the principle of freedom of navigation as a core issue in all regions of the world for NATO Allies and strategic partners beyond; and 3) to relieve pressure on global commodity markets and provide a sustainable solution to food security challenges in Africa, the Middle East and the Global South.

© Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism”

Author:

Yevgeniya Gaber

The information and views set out in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect

the official opinion of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine.

Foreign Policy Council “Ukrainian Prism”

Phone.: +380935788405

Email: info@prismua.org