ADVANCING CHINA’S GLOBAL SECURITY STRATEGY AND EXPANDING ITS PRESENCE IN THE LATIN AMERICA AND CARIBBEAN

Author:

Alina Hrytsenko

Upon coming to power in 2012, Xi Jinping initiated the process of strengthening China’s political positions worldwide. This was evident in massive projects such as the “Belt and Road Initiative” and numerous philosophical-geopolitical concepts like the “Chinese Dream” (中国梦, Zhōngguó mèng), the Community of Shared Destiny for Mankind (人类命运共同体, Rénlèi mìngyùn gòngtóngtǐ), the Global Development Initiative (Global Development Initiative, 全球发展倡议, Quán qiú fā zhǎn chàng yì), and the Global Civilization Initiative (Global Civilisation Initiative, 全球文明倡议, Quánqiú wénmíng chàngyì). All these concepts aim to establish China as a global power, an alternative to the United States, offering a “just” and “mutually beneficial” world order. One component of this package of initiatives and concepts is the Global Security Initiative (全球安全倡议, Quánqiú ānquán chàngyì).

The essence of the Global Security Initiative (GSI) is to address the root causes of international conflicts, improve the management of global security, encourage joint international efforts to ensure greater stability and predictability in an unstable and changing era, and contribute to strong peace and development worldwide. GSI encompasses broad general principles that echo the key tenets of Chinese foreign and security policy. GSI aims to solidify China’s reputation and image as a responsible global player that conscientiously fulfills its obligations as a major power and is ready to serve as a guarantor and provider of global security. This should be seen as China’s statement of intent to aspire to a significantly larger role in international politics. In seeking to establish itself as a leader, Beijing, including through initiatives like GSI, promotes the idea of a more just world order, an alternative to the rules-based order. China contends for leadership positions among developing countries, comprising the so-called Global South, including countries in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC).

The characteristic of Beijing’s modern approach to Caribbean countries and, in general, to the LAC, is encapsulated in the formula “1+3+6”, proposed by Xi Jinping in July 2014 as a new format for relations between China and LAC. In this formula, “1” signifies a unified, coordinated development plan for cooperation between China and LAC countries, “3” represents three cooperation mechanisms involving trade, investment, and finance, and “6” encompasses six cooperation areas: energy resources, infrastructure, agriculture, industry, scientific and technological innovation, and information technologies.

China is increasing its influence in Latin America through various strategies and mechanisms, including the following aspects:

Economic Investments. China is actively investing in the economies of Latin America and the Caribbean, including credits, loans, and direct foreign investments in various sectors such as energy, infrastructure, mining, and agricultural enterprises. Economic cooperation allows China to create a positive image in the region as an alternative to the United States, which has a somewhat toxic reputation due to a complex history of relations with regional states and sometimes strong historical resentments.

Trade. Over the past twenty years, China has become a major trading partner for many Latin American countries. Trade between China and Latin American countries is growing, and China is a significant importer of agricultural products, strategic resources, and minerals from the region.

Energy Projects. China is actively investing in energy projects in the region, including the construction of hydroelectric power stations, power plants using renewable energy sources, and the extraction of oil and gas. This allows China to meet its energy needs and expand its influence in the region.

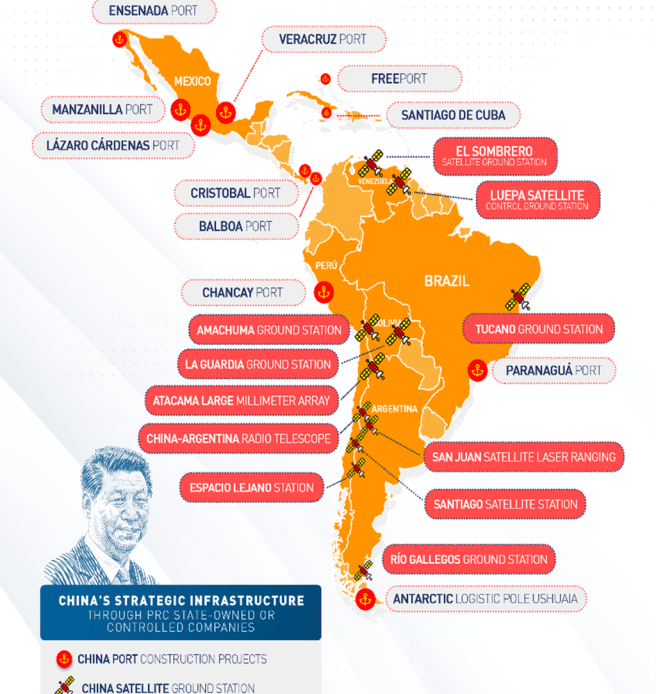

Infrastructure Projects. China is financing and constructing infrastructure projects such as ports, railways, and transportation corridors that contribute to the development of logistics and trade in the region.

Diplomatic Efforts. China is actively developing diplomatic relations with Latin American countries, including leader visits, the signing of bilateral agreements, and participation in regional forums. China interacts with Latin American countries on multilateral platforms such as the China-Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) Forum.

Education and Cultural Exchanges. China is also investing in education and cultural exchanges, strengthening ties between China and Latin America and supporting a positive image of China in the region. The complex Chinese culture and language are promoted through numerous branches of the Confucius Institute established in various countries in the region.

The Essence of the Global Security Initiative (GSI)

GSI was first proposed by Xi Jinping at the annual Boao Asian Forum[1] in April 2022. In February of that year, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China published a conceptual document outlining the key provisions of the Initiative.

Officially, the goal of GSI is to eliminate the root causes of international conflicts, improve the management of global security, encourage joint international efforts to ensure greater stability and predictability in an unstable and changing era, and contribute to strong global peace and development. GSI incorporates broad general principles that echo the fundamental tenets of Chinese foreign and security policy, primarily based on the Panchsheel principles[2] or the “principles of peaceful coexistence”. The document includes “six commitments” and defines priority areas of cooperation:

- Comprehensive, universal, joint, and sustainable security.

- Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all states. According to this point, sovereign equality and non-interference in internal affairs are the fundamental principles of international law and the most fundamental norms regulating modern international relations. “All countries, large or small, strong or weak, rich or poor, are equal members of the international community. Their internal affairs should not be subject to external interference; their sovereignty and dignity should be respected, and their right to independently choose social systems and development paths should be supported”.

- Adherence to the purpose and principles of the UN Charter.

- Serious consideration of the security issues of all countries. According to this point, humanity forms an integral and indivisible security community. This means that the security of one state cannot be realized at the expense and to the detriment of another state, as all states are equal in ensuring security. Each country has fair and legitimate security interests.

- Peaceful resolution of disputes between countries through dialogue.

- Maintenance of security in both traditional and non-traditional spheres (such as terrorism, climate change, cyber security, and biosecurity).

Officially, the GSI aims to “protect the principle of indivisible security, build a balanced, efficient, and resilient security architecture”. In particular, the document outlines tasks that China urges the global community to undertake and assures readiness to make a significant contribution to achieving the stated goals, reflecting China’s leadership geopolitical ambitions. Among the key tasks are: preventing potential nuclear warfare and supporting non-proliferation, promoting the prohibition and destruction of weapons of mass destruction, maintaining global control over conventional arms, promoting the political resolution of international and regional issues in conflict zones through open dialogue, strengthening dialogue on maritime law and combating crimes at sea, including piracy, enhancing international cooperation in outer space, supporting the WHO in health care management, and effectively coordinating and mobilizing global resources for joint response to COVID-19 and other infectious diseases. Additionally, the GSI aims to promote the protection of global food and energy security, ensure stable grain production and supply chain security, and avoid politicization and weaponization of food security. The initiative also seeks to support cooperation between countries in addressing climate change.

Thus, the GSI is intended to solidify China’s reputation and image as a responsible global player that conscientiously fulfills its obligations as a major power and is ready to serve as a guarantor and provider of global security. This should be considered as China’s statement of intent to claim a significantly larger role in international politics.

This confirms the 20 priority areas of cooperation to address key global issues (peace, development, security, and governance) highlighted in the conceptual document of GSI. Within these points, China declares its readiness to promote coordination and healthy interaction among major states and build relationships characterized by peaceful coexistence, overall stability, and balanced development. China, thus, positions itself as one of the major world powers on par with the United States. It emphasizes that large states bear a particularly important responsibility for maintaining international peace and security. This point reflects China’s significant geopolitical ambitions and a clear vision of the future world order and China’s place in it.

GSI envisages the implementation of set tasks through five main platforms and mechanisms. Among these platforms are not only global ones like the UN (including the UN General Assembly and UN Security Council) but also regional organizations, forums, and discussion platforms where China is represented. Specifically mentioned are the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, BRICS, the Conference on Interaction and Confidence-Building Measures in Asia, the “China + Central Asia” mechanism, a multilateral dialogue platform in the Persian Gulf region, meetings of foreign ministers of countries neighboring Afghanistan, the China-Africa Peace and Security Forum, the Security Forum in the Middle East, the Beijing Xiangshan Forum, and the Global Forum on Public Security Cooperation (Liangyun Summit). The emphasis on “non-Western” platforms confirms China’s efforts to promote an alternative world order, where the United States and European states, former metropolises and empires, do not hold the key positions. Beijing’s focus is on countries in the so-called Global South, and the world order concept promoted by China envisions an equal status for former empires and colonies. Moreover, China claims leadership among developing countries that constitute the so-called Global South. Seeking to establish itself as a leader, Beijing, through initiatives like GSI, promotes the idea of a more just world order, an alternative to the rules-based order that, from the Chinese leadership’s perspective, was created exclusively in favor of Western states. A more just world order, as China sees it, involves adequate representation of developing states on global platforms and organizations, including the UN, WTO, and IMF. Despite its economic power and pace of economic development, China still considers itself the “largest developing country” and uses this status to garner support and solidarity from other countries, fostering cooperation along the South-South axis.

In this way, GSI, overall, is an attempt by Xi Jinping to present a comprehensive vision of a new world order and formulate the ideological basis for a new global governance system that enhances China’s influence amid the gradual decline of the United States’ influence on the world stage. GSI concerns all regions of the world, including the conflict-prone region of the Persian Gulf. GSI is fully aligned with the views of regional states on regional and international security, including through the principle of non-interference in internal affairs, which entails no criticism for, for example, human rights violations or the erosion or absence of democratic values.

In the Middle East, the GSI conceptual document calls for creating a “new security structure” based on the Chinese proposal of five points to achieve peace and stability in the region, “including support for mutual respect, adherence to equality and justice, support for the non-proliferation regime, strengthening collective security, and cooperation for development”. Additionally, China promises to use GSI to support the efforts of regional countries in “strengthening dialogue and improving relations, addressing legitimate security concerns of all parties, strengthening internal forces to ensure regional security, and supporting the League of Arab States and other regional organizations that play a constructive role in this regard”. To some extent, the implementation of GSI manifested itself during China’s mediation in normalizing relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Although China’s diplomatic success was influenced by favorable circumstances, including the willingness of both sides to sit down for negotiations to restore communication, China used the successful conclusion of the talks to its advantage as evidence that GSI is a viable and practical initiative.

GSI includes not only the Middle East but also the African continent, the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region, and is actively promoted by Chinese representatives at various levels. For example, following the visit of Colombian President Gustavo Petro to China, support for the Latin American state’s endorsement of GSI was announced, as well as for other related concepts such as the Global Development Initiative (GDI) and the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI).

China’s Penetration into the Latin America and Caribbean

The countries of LAC, which were on the periphery of Ukraine’s foreign policy, have increasingly attracted the attention of Beijing in recent decades. The main objectives that China has pursued in the last 20 years include economic expansion to gain access to the rich natural resources of the region (such as oil, gas, uranium, gold, lithium, copper, silver, diamonds, and more) and reducing Taiwan’s influence in the world. As of October 2023, out of 33 countries in the region, 7 maintain diplomatic relations with Taipei (Paraguay, Haiti, Guatemala, Belize, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia).

Since the 2000s, China has become a key export market for Cuba, Chile, Brazil, Peru, Argentina, and Venezuela. Additionally, it holds the first place among importers for Panama and Paraguay and the second place for Argentina, Venezuela, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. China’s push for exports and investments is driven by the desire to acquire necessary resources to meet the needs of its developing industries, expand markets, and improve the efficiency of existing enterprises. China has achieved success in active economic penetration through mass acquisitions of assets of raw material companies involved in the oil and gas business or mineral extraction.

The main agreements with LACB countries focus on the raw materials sector, particularly in extraction industries, while large investments are directed towards the industrial sector. However, China’s recent interest has also extended to the production of agricultural products, especially in the field of soybean production.

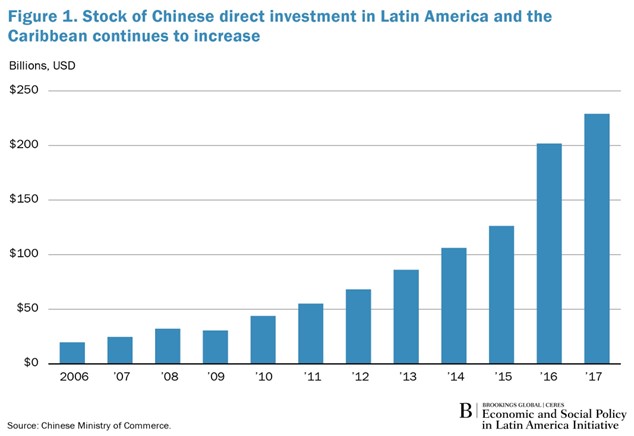

Over the past 20 years, China has managed to secure the second position among the largest investors in LAC countries. Accumulated Chinese investments in the region from 2005 to 2019 ranged from $130 to $140 billion, with Brazil receiving around $60 billion and Peru, rich in copper and hydro resources, receiving nearly $27 billion. The primary direction of Chinese capital investment is in energy projects (56%), with investments in metallurgy and mining accounting for 28%. In addition, the value of Chinese construction contracts in the region has approached $61 billion, with 53% allocated to energy infrastructure and 27% to transportation and logistics. The main recipients of Chinese credits from 2005 to 2019 were Venezuela, Brazil, Ecuador, and Argentina.

LAC is the second-largest global recipient of Chinese investments, with over 2,700 Chinese enterprises operating in the region. Currently, more than 2,000 Chinese companies have invested in the economies of LAC countries, creating over 1.8 million jobs. Typically, the Chinese government provides loans for the construction of projects on the condition that the work is carried out by Chinese companies and the equipment is supplied from China. Thus, China’s approach is based on financing projects designed for its long-term presence in the region.

China, as an investor, is attractive to the countries of the Latin America and Caribbean region for several reasons. Firstly, Beijing does not impose stringent requirements regarding democratization or specific directions for the development of state institutions, and it does not interfere in the internal politics of states, as the United States did. The finances of the U.S. were strictly regulated in terms of their implementation, and overall, they were accompanied by numerous restrictive mechanisms. Secondly, China itself serves as a positive example for developing countries. Unlike developed countries that became wealthy, in part, due to past colonies, China had a different historical background and, despite this, demonstrated long-term economic growth. China, originally an agrarian country lagging significantly behind leading world countries in terms of technology and economics and lacking serious resource potential, proved capable of transforming into a dynamically developing state. In this context, the Chinese model of economic development is attractive to LAC countries, for which transitioning from peripheral countries to developed states is important. This is particularly relevant considering that the LAC region is composed of developing countries, to which China also belongs.

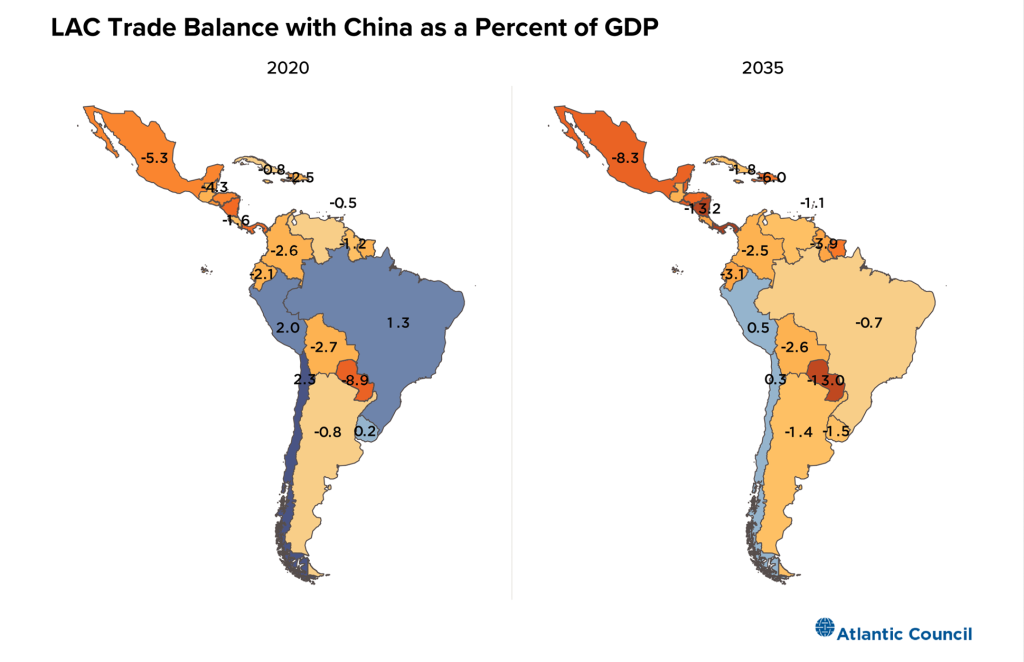

Economic and trade relations are the main vector of Chinese-Latin American interaction. Since the beginning of the century, the total volume of trade between China and LAC has increased from $17 billion in 2002 to nearly $315 billion in 2019. In the years 2018-2019, China’s imports from Latin America accounted for almost 8% of China’s total imports, while exports to LAC constituted approximately 6% of China’s total exports. China has become the main trading partner for Brazil, Argentina, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay, surpassing the United States, and the second-largest trading partner for many other countries in the region.

China mainly imports natural resources from LAC, including ores (32%), mineral fuels (19%), soybeans and soybean oil (16.7%), and copper (5.6%). The major portion of China’s exports to LAC in 2019 consisted of electrical appliances and equipment (21%), machinery and devices (15%), automotive vehicles and parts (6.5%), and a wide range of consumer goods.

China has free trade agreements with Chile, Costa Rica, and Peru. In the last two years, China’s exports and imports to and from LAC have continued to grow, maintaining the trend of the past decade, and even the COVID-19 pandemic has not significantly altered this situation.

Moreover, the pandemic provided China with the opportunity to go beyond its key role as a trade partner and creditor for Latin American countries. China initiated what became known as “mask diplomacy” and even “coronavirus diplomacy” (or “Health Silk Road construction” in China). In LAC, unlike Africa, there were no accusations against China for the spread of infection, except for remarks from Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, known for his skepticism about the coronavirus. Therefore, China’s “coronavirus diplomacy” in LAC had a pragmatic rather than forced nature to improve the country’s international image.

By the end of 2020, China provided masks, protective suits, tests, equipment (monitors, defibrillators, and ultrasound scanners), ventilators, financial aid, and vaccines of Chinese production. The assistance to the region was distributed unevenly, with the main flow going to ideologically aligned countries like Venezuela and Cuba.

The “coronavirus” year 2020 can be seen as a turning point in China’s investment policy towards LAC: for the first time in 15 years, China did not provide any credit to any Latin American country. Meanwhile, Chinese companies shifted their focus from lending to direct investment in Latin American infrastructure, especially in the energy and transportation sectors. This new approach was influenced by the Belt and Road Initiative, in which China wants to involve LAC, and also by the COVID-19 pandemic. The supply of Chinese aid demonstrated its political effectiveness, changing the attitudes of previously skeptical leaders towards China, such as Argentine President Alberto Fernández, who in January 2021 thanked China for supporting Argentina’s fight against COVID-19 and even supported the idea of building a community of shared future for all of humanity. In 2022, Argentina joined the Belt and Road Initiative. In 2023, China intended to start the construction of a 1200 MW reactor at the Atucha nuclear complex in Lima, Buenos Aires province, costing $8 billion, in addition to two hydroelectric power stations already under construction in southern Argentina. It’s worth noting that as of 2023, more than 20 out of 33 LAC countries are participating in the Belt and Road Initiative. Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia, three of the largest Latin American economies, are not yet involved in the project.

During his speech at the 2018 China-CELAC Forum, Wang Yi, the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, highlighted five points of cooperation between the parties within the framework of the “Belt and Road” initiative: the construction of infrastructure connecting “land and oceans”; the establishment of an open market enabling the export of Latin American products; the development of competitive economic sectors in CELAC countries through the transfer of Chinese technology; the promotion of innovation by expanding the Digital Silk Road to the region’s countries; and the exchange of experience in various fields.

As part of the “21st Century Maritime Silk Road”, China plans to create an infrastructure network, a railway that will connect the port of Tianjin (China) to the ports of Bayovar (Peru) and Santos (Brazil), thereby strengthening cooperation within the initiative. The Chinese side stands to benefit from increased delivery speed, as the current route through the Panama Canal is more expensive and time-consuming. It is noteworthy that the port of Tianjin will also encompass the Hebei province and Beijing, leading to the creation of a new free trade zone in China. The advantage of the Tianjin Free Trade Zone is that it integrates the northern region of China, which lags behind the southern provinces.

China’s presence on the continent is advantageous for the countries in the region as it diversifies political contacts and can balance the influence of the United States in the region. The emergence of the People’s Republic of China as a new economic player has put an end to the excessive dependence of countries on Washington, and China has become a card in political bargaining with the United States. China’s approach to cooperation, based on infrastructure development and the absence of rigid mechanisms for controlling financial flows, aligns with the values and priorities of left-wing parties in the region, generating a high interest in developing relations with China.

China’s Interests in the Caribbean

The countries of the Caribbean Basin hold a particular interest for China, as this region is home to the largest concentration of countries that maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan. Consequently, China is keen on altering the situation in its favor, and this is achieved through investments in the local economy. From 2005 to 2022, China invested over $10 billion in six Caribbean Basin countries, including Jamaica ($3.16 billion), Guyana ($3 billion), Trinidad and Tobago ($2.28 billion), Antigua and Barbuda ($1 billion), Cuba ($740 million), and the Bahamas ($350 million). Key sectors that China invests in include tourism, transportation, metal extraction, agriculture, and energy.

The primary forms of Chinese assistance to Caribbean countries are grants and low-interest loans. Grants are typically allocated for the implementation of small to medium-scale socially oriented projects, financing cooperation in human resource development, technical cooperation, material, and humanitarian aid. Low-interest loans provide the borrower with highly favorable conditions—interest rates below 2-3% annually with terms ranging from 15 to 20 years. Such loans are usually granted for the implementation of large and medium-scale industrial and infrastructure projects, as well as for the purchase of machinery, electronic equipment, and materials.

China traditionally shows a significant interest in investing in the exploration of natural resources. While Caribbean countries do not possess extensive reserves of minerals (unlike some South American states), Cuba, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Dominican Republic may be attractive to China in this regard. Cuba has significant reserves of nickel, chrome, iron and copper ores, phosphates, and ongoing exploration of oil and gas deposits. Jamaica is rich in bauxite, Trinidad and Tobago in oil and gas, and the Dominican Republic in bauxite, iron ore, nickel, and copper. In 2011, the China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) signed a $6 billion contract to increase the capacity of the Cuban oil refinery and construct a new liquefied natural gas terminal in the coastal area of Cienfuegos.

China is showing increasing interest in making substantial capital investments in the development of port infrastructure in the Caribbean Basin. The strong dependence of China on the import of energy resources and raw materials, which arrive in large volumes by sea, has led Beijing to place greater importance on expanding access to maritime communications and related infrastructure worldwide, including in the Caribbean Basin. In July 2014, during Xi Jinping’s visit to Cuba, an agreement was signed to provide a $115 million loan for the restoration and modernization of the country’s second-largest port, Santiago de Cuba.

It is worth noting separately that the development of port infrastructure could potentially contribute to the expansion of China’s military presence in the region, as it would increase the presence of Chinese naval forces in the Caribbean. While Beijing is just beginning its path to expanding its military-political influence in the Western Hemisphere, there are already noticeable results: according to The Wall Street Journal, China has reportedly entered into a secret agreement with Cuba to deploy an electronic listening device on an island approximately 100 miles from Florida. The parties are also negotiating the establishment of a joint military training camp on the “island of freedom.” In addition, Beijing has shown interest in the radio-electronic center in Lourdes, the main Soviet, and later the most important Russian foreign center for radio-electronic intelligence. Located in the southern suburb of Lourdes, the Cuban capital Havana, it was used until 2002.

In 2018, at the initiative of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China, the China-Caribbean Press Center was established. The center’s work involves facilitating trips to China for Caribbean journalists. At the same time, it should be noted that such institutions are part of a strategy to expand influence and project soft power, as they facilitate the dissemination of certain narratives and concepts. For example, it helps to establish China’s image as the “leader of the Global South”, advocating for the equality of all states regardless of territorial size or economic power, non-interference in internal affairs, and supporting the political uniqueness of all states. Mostly, this is nothing more than rhetorical manipulation, which, nevertheless, is positively received in the small island states of the Caribbean Basin and Latin America as a whole, which have a long and sometimes negative history of relations with the U.S. and Western European states, former colonies.

China, which Xi Jinping positions as a state that once suffered from European imperialist policies, seeks to solidify its reputation as a champion of a “fairer” world order. By this, Xi understands a world without the dominance of a single hegemon, particularly the U.S. Xi Jinping often says that the world is currently experiencing the greatest geopolitical changes in the last 100 years, understanding this as not only the reduction of U.S. influence in the world but also the strengthening of regional states that were recently under the yoke of colonizers. The theme of shedding colonial past and increasing the role of the state on the world stage is actively exploited by China, including with small, economically weak countries such as Barbados, which in 2021 changed its form of government from a constitutional monarchy to a parliamentary republic (though it remained a member of the Commonwealth of Nations).

During a meeting in Beijing with Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley, Xi Jinping used terms such as “defense of national sovereignty and independence” as well as “independent choice of own development path”. With this, Xi expressed China’s support for Barbados’ break from the British Crown. “Developing countries must strengthen solidarity and cooperation, practice true multilateralism”, said Xi Jinping. This rhetoric is extremely attractive for small or poor countries in the Caribbean and Latin America, as well as for more powerful candidates for regional leaders who are rethinking their place and the region’s place in the world. At the same time, a characteristic feature of the Chinese information-political campaign is the rejection of promoting communist, Marxist doctrines, aiming to confirm Xi Jinping’s statements that “there are no bad states, but each state is good in its own way” and the freedom and independence of choosing political development.

The potential allies of China in the LAC region

Chinese rhetoric is manipulative but attractive, and although it is currently difficult to determine a clear camp of pro-Chinese states in the LAC region, states more willing to cooperate can be singled out. These are predominantly American antagonists such as Venezuela, Bolivia, Cuba, and Nicaragua. Thus, it is not so much pro-Chinese states as anti-American ones that are attracted to China’s non-intervention policy (i.e., providing financial support without additional requirements such as democratic or anti-corruption reforms). However, as demonstrated by the example of Venezuela, these states are willing to cooperate with Washington on attractive terms for their own benefit. At the same time, the policy of rapprochement with China depends largely on the current political conjuncture, as seen in the example of Colombia. The new president, Gustavo Petro, decided to reconsider relations with the United States, reflected, among other things, in the renewal of relations with China to the level of “strategic partnership”. Although for Beijing, this status is symbolic and almost meaningless.

For China, a “fair world order” is polycentric. Speaking of solidarity and equality among all states, it essentially means an uneven distribution of influence among different countries in different regions, regardless of the size of the territory or the strength of the economy, but a fair distribution of influence among comparable regional states. China does not seek to make the LAC a “Chinese backyard” but is ready to share influence with states like Brazil, which is currently a key transmitter of Chinese narratives and concepts. The main reason for this lies in the convergence of the views of Xi Jinping and Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva on the emerging new world order, where the level of American influence in the LAC region is minimized. This also explains cooperation between states within BRICS. Brazil’s geopolitical ambitions under Lula’s third presidency are aimed at consolidating Brazil’s status as a regional leader, a center of influence, and the LAC region as a fully integrated player on the international stage. LAC is currently undergoing transformation, and China contributes to this informationally and, one might say, ideologically.

This year, at the seventh China-CELAC summit, Xi Jinping stated that the alliance is a key partner of China in strengthening solidarity among developing countries and developing South-South cooperation. “China cooperates with CELAC countries to enter a new era characterized by equality, mutual benefit, innovation, openness, and benefit for the people”.

The new era in thought should be characterized by the minimization of the global influence of the United States, a goal also of interest to the Russian Federation (RF). Although currently, the RF and China do not act as a united duo in the LAC region. Russia’s influence in the region has consistently diminished since the collapse of the Soviet Union, and currently, Russian positions are quite weak. The informational presence of Russia is quite widespread thanks to Spanish- and Portuguese-language media outlets such as Sputnik Mundo and RT en Español, which spread Russian propaganda, including distorted and false accounts of Ukraine and the Russian-Ukrainian war. However, the acceptance of Russian propaganda is more noticeable among countries antagonistic to the United States, and it does not contribute to strengthening Russia’s influence in the region. Currently, Russia, already deprived of the status of a regional power, whose level of isolation is increasing due to a toxic reputation, continues to lose connections in the LAC region, as well as in other more significant regions (Caucasus, Central Asia). At the same time, Russia lacks the resources to restore its lost positions. Today, Moscow uses countries such as Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua (almost all of which Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov visited as part of his Latin American tour this spring) as instruments for propaganda for the domestic audience. Russia tries to convince the population that sanctions and the rupture of relations with Europe and the United States will not hinder the country’s further development and that Russia can and will develop political and economic relations with other states worldwide based on ideological closeness. However, these mentioned states form, as mentioned above, an “anti-American camp” and, in turn, use Russia as a leverage against the United States and for the realization of urgent tactical interests. Other countries in the region, except for Brazil, which maintains a neutral position regarding the Russian-Ukrainian war, are not as eager for political communication with Moscow.

Barriers to the Spread of Chinese Influence

Despite this, there are barriers to further political and economic expansion by the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the region. Many states fear intensifying cooperation with China due to ongoing Sino-American confrontation, aiming to avoid giving the impression that the country is choosing one side over the other.

In terms of economic factors, firstly, infrastructure development, particularly in transportation and energy projects, harms the environment and poses ecological risks, leading to a rise in anti-Chinese sentiments. It is noteworthy that China’s ecological standards are lower than those of LAC countries because, like many developing nations, China sacrificed ecology for progress during its economic development. LAC countries have high environmental protection standards due to cultural and legal proximity to developed countries such as Spain and the USA.

Another issue is security. Many countries in the region face a complex criminal environment with drug cartels and gangs whose activities can threaten the safety of Chinese personnel and create obstacles for business operations, including infrastructure construction.

Another problem is political risks. Implementing large projects, especially in the infrastructure sector, takes a considerable amount of time. Many Latin American countries are characterized by turbulent political landscapes, with active political struggles. For instance, Nicaragua experienced diplomatic relations with China during Daniel Ortega’s first presidential term (1985-1990), switched to Taiwan during the presidency of Violeta Chamorro, and reverted to China when Ortega returned to power in 2021.

Additionally, the cultural and legal differences contribute to challenges in labor relations between the Latin American workforce and Chinese employers. While labor law requirements are low in China and some other countries, they are relatively high in Latin America, leading to labor disputes when Chinese companies hire local workers.

To create a positive image, China established a network of Confucius Institutes in the region. It is expected that these institutes will attract public attention to Chinese culture. The institutes aim to explain Confucian values to Latin Americans, which form the basis of China’s foreign policy (unity, harmony, order, justice, tolerance, multilateralism, etc.). This helps promote foreign policy concepts such as the Global Security Initiative.

Conclusions and Recommendations

One of the crucial conclusions for Ukraine in the context of China’s expansion in the Latin American and Caribbean region is the significance of the cultural factor and the promotion of its interests through soft power. One of Ukraine’s key tasks in the region is to consolidate political support, including in the context of the Russo-Ukrainian war. This can be achieved by creating a positive image of the Ukrainian state in the regional information space through cultural diplomacy, Track II diplomacy, and other means. The Ukrainian Institute and the engagement of the Ukrainian diaspora in the LAC, numbering over 1 million people, are essential tools for implementing this task. Informational efforts should also counter Russian propaganda in the region by debunking myths about Ukraine spread by Russian media. Additionally, strengthening the country’s image as a reliable and predictable partner in the new foreign policy and economic partnership with Latin American and Caribbean countries is crucial.

In the context of garnering greater support, it is vital to strengthen political trust and minimize potential differences between Ukraine and the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean regarding major international issues. To achieve this, establishing a system of regular bilateral and multilateral political consultations, activating parliamentary diplomacy through organizing meetings of inter-parliamentary cooperation groups with relevant “friendship groups” in the legislative bodies of the region is necessary. Currently, the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine has seven parliamentary groups for inter-parliamentary relations with Latin American countries: Brazil (17 deputies), Cuba (40 deputies), Mexico (6 deputies), Chile (15 deputies), Argentina (11 deputies), Peru (9 deputies), and Guatemala (6 deputies). There is an obvious significant disproportion in the number of participants, which does not fully correspond to the level of bilateral political and economic cooperation. Therefore, it is advisable to review the composition of these groups, particularly the “friendship groups” with Cuba and Mexico. Moreover, it is essential to revive inter-parliamentary groups with Colombia, Paraguay, and Uruguay, which operated during the previous convocation of the Verkhovna Rada. Equally important is the question of the possibility of opening new diplomatic and consular establishments (consulates in Guatemala and Costa Rica, the latter being the fifth-largest trading partner of Ukraine in the Latin American region), their staffing, and organizational support.

To gain political support and build communication, active participation in the discussion of issues that are urgent for regional states is crucial. It should be recognized that the Russo-Ukrainian war is not a critically important issue for the countries of the LAC, and its impact on Latin American states is indirect. Therefore, attention should be paid to addressing the concerns of the region and promoting mutually beneficial communication. Among such issues, environmental protection and biodiversity stand out, aligning with the 8th point of the Peace Formula of the President of Ukraine. Ukraine suffers from the ecocide caused by the war, while the ecology of Latin American states suffers from the improper use of natural resources for economic gain, leading to environmental conflicts. Issues such as climate change mitigation, poverty reduction, improvement of healthcare systems, and digitization are areas where Ukraine can actively participate as a responsible member of the global community despite being in a state of war.

[1] Also known as the “Eastern Davos”, it is a non-governmental and non-profit international organization aimed at supporting and developing economic exchange, interaction, and cooperation both in Asia and beyond. This is achieved through the annual high-level meetings involving representatives from governmental, business, industrial, and scientific circles to discuss current economic, social, environmental, and other issues. Founded in 2001, after the Asian financial crisis, by 26 countries in the Asia-Pacific region for dialogue on political and business matters. The organization’s headquarters are located in the town of Boao, Qionghai City, Hainan Province, China.

[2] “Pancha Sila” (“Five Precepts”, “Five Principles”) refers to the basic code of Buddhist ethics. It encompasses the five principles of peaceful coexistence, which were first proclaimed in the 1954 Sino-Indian Agreement. These principles include: mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence.

© Centre for International Security

Author:

Alina Hrytsenko

The information and views set out in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect

the official opinion of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of

Ukraine.

Centre for International Security

Borodina Inzhenera Street, 5-А, Kyiv, 02092, Ukraine

Phone: +380999833140

E-mail: cntr.bezpeky@gmail.com