CENTRAL ASIA—THE EUROPEAN UNION (+UKRAINE): PROSPECTS AND CHALLENGES

Author group:

Mykhailo Gonchar, Oksana Ishchuk, Serhii Lesniak

Introduction. Spectrum of interests of external actors.

The Central Asian Five (Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan)—having no outlet to the World Ocean and locked in a continental space between the Caspian Sea in the west and China in the east, Russia in the north, and Iran and Afghanistan in the south—are still inertially within the Russian sphere of influence, weakened by the war against Ukraine. At the same time, the region is of rising strategic importance for the interests of global players such as the EU and China.

The EU has considerable interests in Central Asia, given both its strategic role as a link between Europe and Asia and its vast mineral and energy resources. In fact, the resources of Central Asia are of paramount significance to the EU. Although the market potential of the region with 70 million people is not as substantial as that of China or India, the population is growing rapidly. Along with this, migration challenges for the EU are also mounting, in particular in the context of the consequences of Russia’s aggressive policy towards its neighbors, the situation in Afghanistan and Iran.

Central Asia is not left out of the U.S. attention, although it has been gradually declining since the mid-noughties. In 2005, the Karshi-Khanabad airbase in Uzbekistan was closed, and in 2014, so was the Manas airbase in Kyrgyzstan. And finally, the shameful end of the 20-year military campaign in Afghanistan in 2021 not only undermined Washington’s authority in the region, but also created the impression for Beijing and Moscow of the global weakness of the U.S. and NATO positions. Nevertheless, the United States sees the region as important in the context of countering Chinese expansion. Japan and South Korea view Central Asia in a similar way.

Türkiye is another geopolitical actor that views the region as the natural habitat of the Turkic world and is trying to use it to consolidate and promote its interests. However, despite all of Ankara’s efforts, Central Asian countries are quite cautious about aligning themselves with Ankara’s pan-Turkish and Ottomanist sentiments. Unlike China and Russia, Türkiye does not directly border the region, and this limits its influence.

India, one more historically important player in the region, is less conspicuous. Central Asia is considered part of India’s “extended neighborhood”. Due to the growing Chinese presence in the region and the strategic partnership between Beijing and Islamabad, both having problematic relations with New Delhi, India formulated its Connect Central Asia policy in 2012. However, the country is geographically separated from Central Asia by the Hindu Kush mountains and has no direct access to the region, so Indian leverage is much weaker than that of other global players.

The situation is the same for Pakistan, which is economically present in the region but has limited influences. The latter should be taken into account in Central Asia, yet they are not decisive, and include the influence of radical Islam of the Iranian ayatollahs and the Afghan Taliban, which are clearly anti-Western and of concern to secular regional regimes.

Central Asia was a rather important region for Ukraine by virtue of Soviet chains of production cooperation in certain industries, as well as from an energy perspective—imports and transit of oil and gas from Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan to Ukraine and through Ukraine to Europe. However, in all of Ukraine’s bilateral relations with the countries of the region, a third party has always been discreetly involved—Russia. The latter’s role has always been destructive and aimed at isolating Ukraine from the region and making it difficult for Central Asian countries to engage with Kyiv. In addition, after the 2004 Orange Revolution and the 2014 Revolution of Dignity, authoritarian regimes in the region, both under the influence of Russia and China and fearing the export of a “color revolution”, were not interested in developing relations with Ukraine.

In fact, Russia, by invading Ukraine in 2014, slowed down and then in 2016 blocked trade and economic relations between Ukraine and the countries of the region, exploiting its transit location. Obviously, Russia’s direct armed invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 only further isolated Ukraine from Central Asia. If earlier it was possible to use transport routes bypassing Russia for trade purposes—through the Black Sea, the South Caucasus, and the Caspian Sea—the blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports by the Russian Black Sea Fleet has made this route unavailable.

It is noteworthy that the regimes in Central Asia that have close ties with Russia are now trying to avoid taking a clear position on the aggression against Ukraine by neither condemning it, nor voting in support of Ukraine at the UN, abstaining or even evading voting.

The vectors of development of Russia and Kazakhstan as the leading country in Central Asia are increasingly diverging against the backdrop of Russia’s aggressive policy, creating new zones of tension between them. Given Russia’s vision of Kazakhstan’s northern territories as “primordially Russian lands” and Astana’s lack of support for Moscow in the war against Ukraine (according to the Kremlin), Russia may plan a “special military operation” against its southern neighbor, but it is unlikely to be capable of waging a war on two fronts simultaneously.

EU—Ukraine—Central Asia: Raw materials perspective.

The problematic behavior of the EU’s important trading partners, China and Russia, has forced Brussels to diversify its critical imports. In the case of Russia, this applies primarily to energy resources, and in the case of China, to critical raw materials (CRMs), which are key to the production of high-tech products, the functioning of the digital economy, the green transition, and Europe’s security and defense.

As a matter of fact, in Central Asia, the EU is challenging China, which has long viewed the region as its raw material appendage located on its western border. First and foremost, this concerns energy resources, but Beijing is increasingly paying attention to the CRMs from the standpoint of maintaining China’s monopoly or dominant status in their supply to Western economies, especially the EU.

The EU has formulated the goals of its minerals policy, among which the following are key:

- ensuring sustainable supply of critical raw materials from third countries;

- formulation and inclusion of conditions for access to mineral resources in all bilateral and multilateral trade agreements of the EU with third countries;

- creation of mineral resource complexes in countries with relevant resources.

(See Annex 1. EU: critical raw materials)

In September 2022, EC President Ursula von der Leyen announced a legislative initiative on CRMs to overcome the EU’s dependence on China: “We must avoid becoming dependent again, as we did with oil and gas”[1].

The EU, and Germany in particular, is interested in cooperation on CRMs, especially in the area of rare earth metals (REMs). The German economy is in a state of alarm. According to some estimates, Germany’s dependence on CRM supplies, especially from China, is much more serious than its dependence on Russian energy. If their supply is cut off, it will have a multiplier effect on German industry. As many countries consider mining for REMs too expensive and dirty, China is taking advantage of its dominance, and partly monopoly, of the global REMs market, and this could become a problem in the near future. “Without these resources, there will be no transition to renewable energy sources, no electromobility, no digitalization, no Industry 4.0, but also no infrastructure development and no competitive defense industry”, warns Siegfried Russwurm, president of the Federation of German Industries (BDI)[2]. According to the European Commission’s 2020 analysis, 65% of raw materials for electric motors are imported from China. The production of wind turbines and solar panels is provided by more than 50% of China’s fossil resources[3].

Therefore, laying the groundwork for EU cooperation with Central Asia on the supply of REMs is essential for the future in case Beijing stops exporting them or the West reacts with sanctions to the deterioration of the situation around Taiwan.

Unlike oil and gas, there are no national reserves of REMs and minerals necessary for modern industry, and the EU countries and Germany in particular are very vulnerable to mineral resources. The German expert community has already suggested that, by analogy with the “turning point” in the energy sector proclaimed by Chancellor Olaf Scholz after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the supply of CRMs and minerals in general to Germany should become strategically important for national security.

Effectively, the EU looks at Ukraine and Central Asian countries mainly from the point of view of access to CRMs. The problem is that in the case of Asian countries, Europe has to deal with authoritarian regimes that are basically not much different from Russia or China. In the case of Ukraine, the EU is dealing with a democracy that is located in the EU’s neighborhood, has a short logistical leverage, but does not have the same raw material diversity as in the case of Kazakhstan. However, Ukraine’s subsoil and the Donbas coal piles and mining dumps in other regions accumulated over centuries of coal mining are attractive raw materials for processing.

Ukraine—EU: raw materials synergy?

The EU member states’ priority countries for supplying their economies with critical raw materials are mainly their neighbors, and this is beneficial from both logistical and geo-economic perspectives. Ukraine is a neighboring country of the EU, and moreover, since 2022, it has been a candidate for EU membership.

Ukraine has adopted a national program for the development of the mineral resource base until 2030, which aims to transform the country into a state that is an integral part of the global mineral resource complex in terms of the use of strategically important minerals and the scale of foreign investment.

A report by a representative of the State Commission of Ukraine for Mineral Resources at the 7th International Scientific and Practical Conference “Subsoil Use in Ukraine. Investment Prospects”, which took place in Lviv in November 2021, highlighted the following: “Having analyzed the data of the state balance of mineral reserves and existing deposits of Ukraine, and comparing them with the positions presented in the table of critical positions for the European Union, we can note a certain resource potential of our country, which makes it possible to establish production and supply of the vast majority of certain elements[4]… According to the proven reserves and forecasted resources of lithium, Ukraine can be considered the richest country in Europe. It can not only fully satisfy its needs, but also meet the demand of the European market for lithium raw materials[5]… The main contenders for involvement in mining are such critical raw materials as titanium, lithium, beryllium, and natural graphite”[6].

Prime Minister of Ukraine Dmytro Shmyhal, during his speech at a business forum on the EU-Ukraine strategic partnership in the raw materials sector as part of the European Raw Materials Week in November 2022, underlines the following: “Ukraine is ready to work with the EU to achieve full independence from Russian resources. In 2021, Ukraine was among the top 10 countries in terms of titanium, iron ore, kaolin, manganese, zirconium, and graphite production. Of the 120 types of minerals consumed in the world, 117 are found in Ukraine’s subsoil. Moreover, we have deposits of 22 out of 30 minerals that are on the EU’s list of critical minerals. These include lithium, beryllium, rare earth elements, nickel and cobalt”[7].

In addition, one should note that Ukraine has a considerable amount of technogenic waste, which is, among other things, a raw material for REM extraction. The accumulated volume is estimated at 35-36 billion tons[8]. This is comparable to the volume of waste from the mining and metallurgical complex of Kazakhstan of 30 billion tons[9].

At the November 2022 Raw Materials Week in Brussels, Vice President of the European Commission Maroš Šefčovič pointed out: “By integrating Ukraine in EU value chains, we will diversify our supplies, strengthen our industrial base, while helping reconstruct Ukraine’s war-torn economy. This will also contribute to our efforts to prevent raw materials from being weaponized”[10]. “Our partnership can be a win-win, bearing fruit for both sides. For Ukraine, it will help approximate its policies and regulatory frameworks to the EU, as well as develop and better integrate the raw materials and batteries value chains in our internal market… For the EU, it will be a key part of our efforts to diversify our sources of critical raw materials, while strengthening our European know-how and industrial base— crucial to preserve our global competitiveness”[11].

Central Asia—EU: critical raw materials.

In June 2019, the EU adopted a new Strategy on Central Asia[12], which outlines its strategic interests in the region and proposes to build a stronger partnership to help the region develop as a more resilient, prosperous and closely interconnected economic and political space. The Strategy declares three priority areas of the EU’s relations with the CA region[13]:

- investment in regional cooperation;

- partnership for increased resilience of Central Asian countries;

- partnership for prosperity with a focus on the accession of the region’s states to the WTO.

The new EU strategy also focuses on the preparation of the EU’s assistance program for the period of 2021–2027. The negotiation of “new generation” Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreements with Central Asian countries has provided a powerful tool for forging a more modern and diversified partnership that goes beyond the “trade and aid” agenda.

Having allowed China and Russia to consolidate their control over the Central Asian region since the beginning of the 21st century, the EU has only now realized its importance in the context of the success of the green transition and the end of the era of fossil energy and dependence on Russia. A green transition is impossible without access to CRMs. And Central Asia, and Kazakhstan in particular, is the “Klondike” of the CRMs.

EU countries actively invest in Central Asia. The head of European diplomacy, Josep Borrell, cited illustrative statistics: “The EU accounts for more than 42% of the total FDI stock in Central Asia, compared to 14,2% for the U.S., 6% for Russia and 3.7% for China”[14]. Kazakhstan is an indicative example. According to Astana’s statistics, over the past 30 years, more than $160 billion in EU investments have been attracted to Kazakhstan’s economy[15]. The EU’s trade with the countries of the region is also expanding (see Annex 2. Trade and Economic Relations, EU Financial Assistance to Central Asia.).

Nevertheless, it is not Europe that dominates the region, but Moscow and Beijing, which are close to the local authoritarian regimes. Of course, Central Asian regimes are interested in the EU market as a solvent and highly profitable one. But, as J. Borrell notes, the countries lack access to European and global markets that do not pass through Russia or do not depend on it[16]. There are routes bypassing Russia—through the Caspian Sea and the South Caucasus, and then through Türkiye or the Black Sea and Ukraine or Romania to Europe. However, the problem with these routes is the challenge of synchronizing the interests of a large number of countries, national customs regimes, and most importantly, Russia’s covert and overt opposition, through pressure on both Central Asian and South Caucasian countries.

The key country in Central Asia is Kazakhstan. The EU prioritizes this country in its relations with the region. The visit of European Council President Charles Michel to Astana on October 26-27, 2022, and the signing of a Memorandum of Understanding on a strategic partnership in the field of raw materials, batteries and renewable hydrogen by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen and Kazakh Prime Minister Alikhan Smailov on November 7 this year clearly indicate what the EU seeks to obtain from Kazakhstan[17]. At the summit in Samarkand on November 20, the head of European diplomacy, J. Borrell, emphasized that Kazakhstan is a major partner of the EU as a primary source of oil imports (about 8% of total EU imports), as well as gas, uranium and other important raw materials[18].

Particular attention should be paid to the fact that Central Asia is rich in uranium raw materials. Its extraction, enrichment and export are of global importance. Kazakhstan ranks second in the world in terms of uranium reserves and is the world leader in terms of production, while Uzbekistan is 9th in terms of reserves and 5th in terms of production (for comparison: Ukraine ranks 6th in terms of reserves and 9th in terms of production, Russia stands 10th and 7th, respectively)[19] [20].

The uranium sector of Kazakhstan is, however, effectively controlled by Rosatom through a joint venture between Kazatomprom and Rosatom’s subsidiary Uranium One Inc, which is the fourth largest uranium producer in the world[21]. In fact, by using Moscow’s political pressure on Astana and eliminating competition in the global market, Rosatom has taken over uranium mining in Kazakhstan. In total, supplies from Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan cover 50% of the U.S. demand, which has already created a problem for U.S. national security in the context of Russia’s threats to stop supplying uranium to unfriendly countries.

Rosatom also tries to impose its own nuclear power plant construction projects on both countries based on the Belarusian scheme. It has already reached a preliminary agreement with Uzbekistan on the construction of a two-unit nuclear power plant. If these projects are implemented, they will become another chain of keeping the leading Central Asian countries in the zone of Russian influence and hindering their cooperation with the EU.

For the EU’s green transition, four technologies play a particularly important role in energy conversion and create dependencies on specific CRMs: solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles, and electric batteries[22]. Kazakhstan has deposits of 16 out of 22 CRMs. Thus, it is a core supplier of materials for clean energy technologies needed for a green transition. Uzbekistan is the second with 11 positions, while Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan have high potential only for some of the CRMs[23]. Turkmenistan is not reviewed given the lack of transparency in the country in general and in terms of access to geological information in particular.

China—Europe: Competition for Central Asia.

Unlike the EU, China has 3,300 km of border with Central Asian countries and is working to secure supply chains through its global Belt and Road Initiative. The BRI is part of China’s “Going Out” policy, which was launched in the 1990s and is aimed at acquiring mineral resources, capturing a share of foreign markets, purchasing foreign technology, and creating a number of global Chinese brands[24].

In addition, the main deposits of CRMs are located in Eastern Kazakhstan, which borders on Western China—Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Chinese companies already dominate the production of CRMs in Kyrgyzstan (9 companies) and Tajikistan (8 companies), where they hold the majority of licenses. Although Uzbekistan opened to foreign investors only in 2016, it has the potential to become a leading regional exporter of critical materials for clean energy technologies in the near future[25].

China has emerged as the top importer of most of Kazakhstan’s CRMs. The EU and the U.S. are not among the major importers. Traditionally, Russia was the main importer of mineral resources from Central Asia in the 1990s and 2000s, but China took over this role after 2010. China dramatically increased its imports of Kazakh zinc, lead, copper, and other minerals after 2017[26]. Imports of molybdenum, which is used in the production of wind turbines, are indicative. It increased by 444% in 2020 compared to 2017. Kazakhstan became the second largest exporter of chromium to China after South Africa in 2019. Nickel and cobalt, which China imports from Central Asia, are used in the production of lithium-ion batteries.

Considering China’s demand for CRMs and convenient location of the region, Central Asia’s mineral exports will continue to grow, along with its economic and political importance, and Beijing’s ambitions to isolate the region from the West, especially the EU and the U.S. At the same time, China will do everything to prevent the EU from becoming independent of Chinese supplies of chemicals and impede Western investors from gaining a foothold in the mining sector of Central Asia, similar to what happened in the 90s and 2000s in the oil sector of Kazakhstan, where the mega-projects Tengiz, Kashagan, and Karachaganak were implemented, each worth tens of billions of euros.

Kazakhstan is one of the first countries to clearly state that it will jointly develop the BRI with China. The Kazakhstan-2030 development strategy is in line with the Chinese initiative. Since its implementation began in 2013, 11 international transport routes have passed through Kazakhstan, including 6 cross-border highways, such as the Shuangxi Highway with a total length of 2,700 kilometers, as well as 5 routes leading to the Persian Gulf and Southeast Asia. Cross-border rail lines have turned Kazakhstan into a transit transportation hub. After the opening of the China Railway Express, Kazakhstan became a transit country on the way to Europe, and the time of cargo transportation was significantly reduced, taking only 6 to 13 days.

China’s expansion in the region is particularly evident in the weaker countries of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Both have reached a high level of dependence on Chinese loans, which allows them to be considered among the group of countries falling into the “Chinese debt trap” (Djibouti, Sri Lanka, Laos, Pakistan, Montenegro, Albania, etc.)[27]. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan’s CRMs is an area where China can gain control over the mining infrastructure in exchange for debt relief[28]. In 2011, Tajikistan’s parliament voted to ratify an agreement to transfer about 1,000 square kilometers of territory to China in exchange for the waiver of a large outstanding debt, amounting to hundreds of millions of dollars. The gold mining concession turned out to be another way to pay off the debt[29].

In summary, China, with its close proximity to Central Asia and, above all, to the region’s largest country, Kazakhstan, has a strategic advantage over the European Union in the competition for both influence over like-minded authoritarian regimes, and CRMs.

EU—Ukraine—Central Asia—China: Energy dimension.

Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan have significant deposits of energy resources. Kazakhstan deposits oil (12th in the world in terms of reserves[30]) and Turkmenistan deposits gas (6th in the world[31]). For a decade and a half after the collapse of the USSR, Ukraine was a consumer and transit country for oil and gas from these two Central Asian countries. Russia has been making systematic efforts to isolate Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan from transit through Ukraine to Europe and to stop direct energy imports from these countries. In general, Russia has succeeded.

Currently, oil exports from Kazakhstan are carried out exclusively through the territory of the Russian Federation—either in the direction of the port of Ust-Luga via the Atyrau-Samara pipeline and then the BPS-2, or to the Black Sea. Russia has virtually cut off Kazakh oil from the Druzhba pipeline, which used to deliver part of its exports to Central Europe via Ukraine (see Map-Scheme 1).

https://jpt.spe.org/caspian-oil-and-gas-leverages-strengths-to-survive-in-a-low-carbon-world

Another direction of oil exports from Kazakhstan is the Yuzhnaya Ozereyevka terminal on the Black Sea through the Tengiz-Novorossiysk pipeline, where oil from European and American investors from the Kashagan, Tengiz, and Karachaganak megaprojects is transported (see Map-Scheme 1 above).

The story with Turkmen gas is similar. Traditionally, it came to Russia through the Central Asia-Center pipeline system built in Soviet times. Under the substitution scheme, it was delivered to Ukraine and Europe, as well as transited through the Ukrainian gas transportation system. Since 2009, due to an artificially created accident on the pipeline, Russia has sharply restricted gas imports from Turkmenistan, as it competed with Gazprom’s supplies to Ukraine and the EU (see Map-Scheme 2).

http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/6649169.stm

At the same time, Russia has made and still makes efforts to prevent Turkmenistan, Türkiye and European companies from implementing projects related to the supply of Turkmen gas to Europe via a route independent of Russia. In the 2000s, the EU included Turkmen gas in its ambitious Southern Gas Corridor plan, part of which is already in operation to transport gas from Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz field in the Caspian Sea through Georgia to Türkiye, and from there, via the TANAP pipeline and the Trans-Adriatic Gas Pipeline, to the EU market. The plan envisaged that Turkmenistan would supply about 30 billion cubic meters of gas annually through the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline and export the gas to Europe via the above route[32]. However, the Trans-Caspian and Nabucco projects have remained on paper for two decades due to Russia’s explicit and implicit opposition, the EU’s weak political will, and the longstanding politically motivated bias of the EU’s leading political and economic power, Germany, towards “cheap Russian gas” (see Map-Scheme 3 above).

On December 14, a trilateral Türkiye-Turkmenistan-Azerbaijan summit was held in Avaza on the issue of Turkmen gas delivery, where R. Erdogan supported the creation of a new gas pipeline that could reduce Europe’s dependence on Russia: “We carry Caspian Sea gas to Europe via (the existing) corridor, which is the backbone of the Trans-Anatolian natural gas pipeline…We need to launch work on transporting Turkmen natural gas to Western markets in the same way”[33]. However, the question still remains whether the Trans-Caspian project will eventually be implemented or, as has happened many times over the past quarter century, will turn out to be another false start, given Russia’s obsession with expanding the Turkish Stream and creating a gas hub on Türkiye’s border with the EU for its own gas, thus blocking the appearance of Turkmen gas on the European market.

China is taking full advantage of the EU’s lack of activity in the region, the Central Asian regimes’ dependence on Russia, their involvement in Russian integration alliances (CIS, CSTO, EAEU), and Russia’s opposition to diversification projects in the European direction. In fact, it has taken over the lion’s share of Turkmen gas exports and part of oil exports via the Atasu-Alashankou route from Kazakhstan (see Map-Scheme 3).

Source: https://apjjf.org/-M-K-Bhadrakumar/3277/article.html

Turkmenistan’s economy relies on gas exports, which account for about 80% of government revenues. Gas exports from Turkmenistan to China are the main source of budget revenues[34]. Turkmenistan supplied about 34 bcm of gas to China, becoming the largest exporter of natural gas to China in 2021[35]. After the fourth leg of the Turkmenistan-Uzbekistan-Kazakhstan-China gas pipeline was completed, the construction of which was agreed upon by Xi Jinping and Serdar Berdymukhamedov during this year’s SCO summit in Samarkand, Turkmen gas exports to China should increase to 65 bcm per year[36]. This project is therefore the biggest competitor to Russia’s Power of Siberia-1 and -2 pipelines in the Kremlin’s attempt to reorient supplies to the east. Putin’s idea of a gas union of Russia, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan using existing infrastructure was met with a negative response from both Central Asian countries.

Now, amid the crisis in relations with Russia, caused by both its aggression against Ukraine and Gazprom’s non-market behavior in the gas market, the EU is frantically looking for alternatives to Russian gas. Brussels and Ankara have brought Central Asian gas up for discussion. Yet, a key factor will be the consolidated support of the United States and the EU for gas production and transportation projects from Turkmenistan to the EU. Had the United States not supported oil and gas production projects in Azerbaijan in the 1990s, the great oil of the Caspian Sea and the gas of Shah Deniz would have remained a thing in itself.

If the United States returns to active support for production and transportation projects in its Central Asian policy, based on its geostrategic interests in containing China, and acts in concert with the European Union, Turkmenistan’s gas could become a reality on the EU market by the end of the decade.

Synergy between the U.S. and the EU would help weaken the influence of Moscow and Beijing in Central Asia and the South Caucasus, which would provide more freedom of action for the countries of the region in implementing projects that were blocked by Russia. First of all, this is the Trans-Caspian gas pipeline project.

Still, it seems that it will be very difficult to overcome Chinese and Russian influence on Ashgabat. Ankara’s position could help, but Türkiye is increasingly leaning toward situational alliances with authoritarian regimes in Asia and is less willing to assist the United States and the EU. Moreover, the regimes of Central Asian countries have not overcome their fear of the threat of “color revolutions”, which they regard as orchestrated by the West. Turkmen-Russian ties remain strong. The first two foreign visits of the newly elected President of Turkmenistan, Serdar Berdymukhamedov, to Moscow and Tehran in March 2022 are indicative. They are a sign of Turkmenistan’s foreign policy orientation.

For Ukraine, the success of projects to produce and transport gas from Central Asia to Europe would have some significance in terms of diversifying supplies. Turkmen and Azerbaijani gas could be supplied to Ukraine and Moldova in reverse from the Romanian direction, using the free capacity of the Trans-Balkan gas pipeline, which was bypassed by Gazprom after the implementation of the Turkish Stream project.

China—Europe: the Middle Corridor.

Despite the complication of relations between China and the EU in the context of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and Beijing’s refusal to join Western sanctions against Russia, trade and economic relations between the parties have been developing, albeit with a large negative balance for the EU. EU imports from China totaled €363 billion in 2019, while EU exports to China amounted to €198 billion. In 2021, the figures climbed to €472 billion of Chinese imports to the EU and €223 billion of EU exports to PRC[37].

On April 1, 2022, the EU-China summit took place, and on July 19, the 9th High-Level Economic and Trade Dialogue (see Annex 3. EU—Central Asia Summit). Brussels’ position is that the EU and China are key trading partners with a shared commitment to formulate joint responses to global economic and trade challenges, supply chain disruptions, and global food insecurity. The EU clearly presented the position that “Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine is creating considerable challenges for global security and economy”[38].

Despite the deterioration of bilateral political relations, “the EU has remained committed to engagement and cooperation given China’s crucial role in addressing global and regional challenges… The EU continues to deal with China simultaneously as a partner for cooperation and negotiation, an economic competitor and a systemic rival”[39].

In fact, against the backdrop of political disagreements caused by both Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the issues of Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Xinjiang, the EU and China agreed to continue cooperation to prevent disruptions in supply chains and the need to exchange information on the deliveries of certain critical commodities, as well as on global food security.

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine and the EU’s sanctions against Russia are making adjustments to EU-China relations. Although China has not joined the sanctions against Russia, it has no desire to be subjected to secondary sanctions, and therefore is trying to optimize its trade and logistics schemes accordingly.

In particular, this refers to the possibility of making more use of other routes of the BRI project than the main route through Russia and Belarus to Europe. Within this perspective, the Middle Corridor—through Central Asia (Kazakhstan), the Caspian Sea, the South Caucasus and the Black Sea—is becoming especially important (see Map-Scheme 4).

https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/central-asia%E2%80%99s-growing-importance-globally-and-eu_en

On March 31, 2022, four countries—Georgia, Azerbaijan, Türkiye, and Kazakhstan—signed a statement on the development of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR). It is planned to establish a joint venture between Georgia, Azerbaijan, Türkiye and Kazakhstan by mid-2023[40]. Kazakhstan, together with the countries of the South Caucasus, is interested in developing the Middle Corridor with access to the EU, both to increase transit cargo from China to Europe and to increase export and import flows between the EU and Central Asian countries. It is notable that Kazakhstan wants to use TITR to export uranium raw materials in order to diversify its supply routes, which currently run exclusively through Russia[41].

For Ukraine, the northern leg of the Middle Corridor—through the Black Sea to the ports of Odesa region—will be of great importance. Its potential is also recognized in Scandinavia[42]. Nevertheless, the prospect of this route will appear only after the demilitarization of the Black Sea and the liquidation (withdrawal) of the Russian Black Sea Fleet from the Azov-Black Sea basin.

Ukraine between the EU and China: A debt trap scenario?

Ukraine has already been in a debt trap—the Russian one. “Cheap gas” from Gazprom has come at a heavy cost to the state for a quarter of a century. Although the country managed to escape from the Kremlin’s debt trap, and Naftogaz of Ukraine also secured compensation from Gazprom through the courts, the war unleashed by Russia is also part of this price.

In parallel with the Russian gas and naval noose tightened by the 2010 Kharkiv agreements, Kyiv under Yanukovych’s presidency began to forcefully develop a strategic partnership with China and abandoned Euro-Atlantic and European integration. The Revolution of Dignity in 2014 and Russian aggression against Ukraine led to the country’s return to the EU and NATO.

However, the Chinese vector, despite the changes in Ukraine’s political Olympus, remained inertially preserved. In fact, this led to Ukraine being at risk of falling into the Chinese debt trap. Beijing’s unfriendly policy toward Ukraine was exposed in full during Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. Although the country’s political leadership’s turn away from China has not yet been finalized, it is virtually inevitable against the backdrop of the Russia-China partnership and Beijing’s de facto refusal to support its strategic partner Ukraine. Moreover, the attempts of some members of the political leadership to engage China in the process of post-war reconstruction of the country are frowned upon by the U.S. and the EU, which are Ukraine’s main donors, and may become an obstacle to its accession to NATO and the EU.

Further, in the postwar period, Ukraine needs to avoid a debt trap in its relations with the EU, which is likely to try to compensate for the losses from the “war in Ukraine” by imposing unilaterally favorable conditions for access to the CRMs. It is important to achieve a synergy effect of EU-Ukraine cooperation so that Ukraine develops not only the extractive sector of the CRMs, but also the processing sector, along with high-tech production of energy equipment for the green transition and further digitalization of the economy and social sphere.

In order to achieve the synergy effect, it is necessary to create conditions for large foreign funds, banks and EU investment companies right now, with an emphasis on giving priority to the right to participate in investments in the development of critical raw materials in Ukraine in the process of its post-war reconstruction. The issue of critical raw materials is crucial for the EU, given the problematic relations with China and Russia, which were seen as the main source of raw materials.

Conclusions. Recommendations.

The assessment of Kazakh MP Kanat Nurov reflects the essence of the amorphous foreign policy of the countries of the region, which are trapped in the continental depths of Asia: “…Multi-vectorism is dangerous today, but right now it is necessary to follow this course in practice in order not to be drawn into an international conflict. And this is very difficult, given the geographical location of our region. Our countries also need to pursue a multi-vector approach in order not to be mere satellites of Russia”.

In the current state of affairs, it would be advisable for Central Asian countries to maximize cooperation not only with the European Union but also with the United States, but anti-Western stereotypes and suspicions make it impossible to do so.

The EU cannot claim to behave like a separate state, and its diplomacy in the region is a “patchwork of 27 member states”[43]. Therefore, the EU’s policy toward Central Asia is slow in development and implementation, and only crises force the EU to accelerate.

At the October summit, the leaders of the EU and the five Central Asian countries reaffirmed their intention to strengthen their overall cooperation, which was an indicator of some rapprochement caused, among other things, by Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, which frightens both the EU and the Central Asian countries.

The five Central Asian countries are forced to constantly weigh the cost of economic and political dependence on Russia in the context of preserving their own territorial integrity, taking into account Russia’s expansionism. Kazakhstan is in a particularly vulnerable position, as Moscow considers its northern territories to be Russian and the country to be artificially created.

The assistance provided by the European Commission to the Central Asian countries makes the EU the first aid donor in the region. It reached €1.1 billion in the period from 2014 to 2020. For comparison, the total amount of concessional EU credit assistance received by Ukraine in 2014–2020 under 5 programs reached €4.41 billion[44]. Due to the Russian aggression, the EU’s macro-financial assistance to Ukraine for 2023 is planned at €18 billion. This is evidence of the EU’s higher priority for the neighboring country compared to the remote region of Central Asia with authoritarian regimes at the helm.

Kazakhstan, rich in hydrocarbons, CRMs, and uranium, is at the center of China’s global BRI project, which aims to gradually establish control over the country’s economy, drive Western companies out of the region and limit Russian influence.

The EU’s interconnectivity strategy, dubbed the Global Gateway, with over €300 billion in technology and infrastructure spending, is seen by many as an attempt to respond to the BRI, but it remains to be seen whether the EU will have sufficient financial capacity to counter the Chinese project.

Amid Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, Russia’s transit blockade of Ukrainian exports to Central Asia, and the lack of direct access to Central Asia, the prospects for economic cooperation with the countries of the region look dim. The example of Kazakhstan, with which the volume of trade relations has decreased four times over the past 10 years, is illustrative[45].

Without the restoration of freedom of navigation in the Black Sea, Ukraine’s trade with Central Asian countries through the South Caucasus and the Caspian Sea is impossible. A resolution of the European Parliament on freedom of navigation in the Black Sea is needed, with appropriate further steps by the European Commission in cooperation with NATO. This will also help to revive trade between the EU and Ukraine with Central Asian countries via the TITR, the South Caucasus, and the Black Sea.

Kazakhstan, as the flagship country in Central Asia, although its leader has changed, continues to remain in Russia’s sphere of influence and politically views Ukraine as a problematic pro-Western state, and economically as an agricultural competitor in the global grain market. With this in mind, relations with Kazakhstan should be approached exclusively through the prism of trade relations. This also applies to other Central Asian countries.

Ukrainian diplomacy should cooperate with the U.S. and the EU and focus on sanctions against Rosatom and its subsidiaries in Central Asia to weaken Moscow’s nuclear lobbying influence in the region and in general. In the case of the EU, the European Parliament Resolution of May 19, 2022, No. 2022/2653 (RSP) calls for “an immediate and complete embargo on Russian imports of oil, coal, nuclear fuel and gas”.

Ukraine needs to advocate for a change in the EU and the U.S. approach to uranium imports from the existing scheme through Rosatom’s subsidiary Uranium One Inc. to a scheme of direct purchases from a Kazakh producer and delivery of raw materials via a route independent of Russia using the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route.

Ukraine’s cooperation with the EU in the field of CRMs is strategically important for both sides. It is vital to achieve synergy of efforts, and for Kyiv to avoid the debt trap by developing cooperation. In the post-war period, Ukraine can become a center for the production of high-tech components within the framework of European cooperation and equipment for the green transition, not only based on its own raw materials, but also from Central Asia.

It is essential for the Ukrainian side to see the processes taking place in relations between the EU and the countries of Central Asia. Therefore, it is advisable to consider the possibility of joining the EU-CA dialogue events as an observer (at the level of ambassador in the respective CA country or in Brussels, depending on the venue), using the candidate status.

Annex 1

EU: critical raw materials.

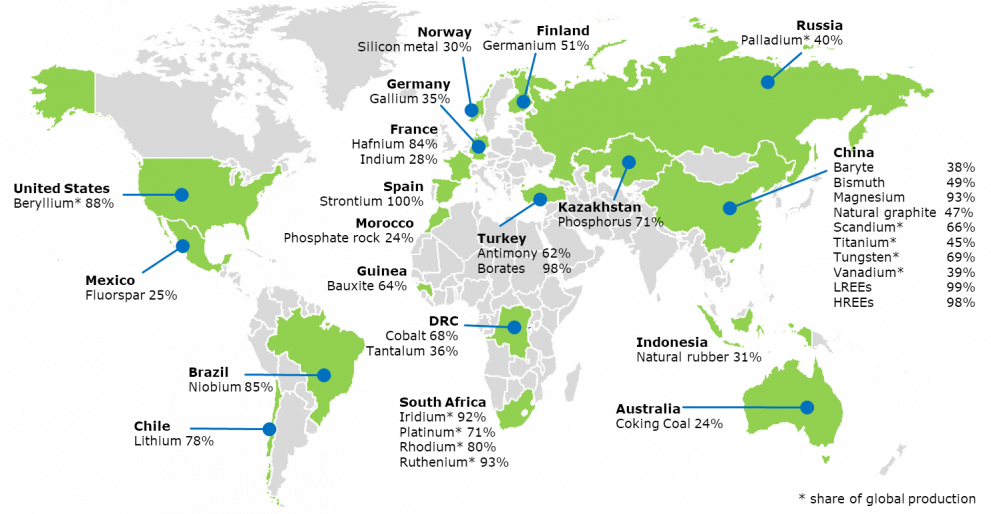

In 2020, the EU revised and expanded the list of critical raw materials. The list was significantly expanded to include 30 CRMs, compared to 14 in 2011 or 27 in 2017[46]. Bauxite, lithium, titanium, and strontium were added to the list for the first time.

| Critical raw materials for the EU, 2020: | ||

| Antimony | Hafnium | Phosphorus |

| Barite | Heavy Rare Earth Elements | Scandium |

| Beryllium | Light Rare Earth Elements | Silicon metal |

| Bismuth | Indium | Tantalum |

| Borate | Magnesium | Tungsten |

| Cobalt | Natural graphite | Vanadium |

| Coking coal | Natural rubber | Bauxite |

| Fluorspar | Niobium | Lithium |

| Gallium | Platinum Group Metals | Titanium |

| Germanium | Phosphate rock | Strontium |

CRMs are divided into three groups according to the level of supply risk:

- low supply risk: gallium, hafnium, magnesium, natural graphite, scandium, metallized silicon, titanium;

- medium level of supply risk: barite, beryllium, bismuth, cobalt, coking coal, fluorspar, heavy and light rare earth elements, tantalum, niobium, phosphorite, phosphorus (apatite), lithium, strontium;

- high supply risk: stibium, boron, germanium, platinum group metals, tungsten, vanadium, bauxite.

Countries that account for the largest share of CRMs supplies to the European Union:

Annex 2

Trade and Economic Relations, EU Financial Assistance to Central Asia.

Although the EU is the first trading partner in the CA region, the overall EU trade turnover with Central Asia remains low. The EU is Kazakhstan’s most important trading partner, accounting for almost 30% of Kazakhstan’s foreign trade in 2021. Exports to the EU are almost entirely in the oil and gas sector, along with minerals, chemicals, and food. From the EU, Kazakhstan imports machinery (32% of total Kazakh imports), chemicals (25%), including pharmaceuticals (15% of total imports), transport equipment (12%), and agricultural products (7%). In 2021, exports from Kazakhstan to the EU amounted to €17.5 billion, and imports from the EU to Kazakhstan totaled €5.6 billion.

In 2021, EU imports of goods from Tajikistan amounted to €162 million, including textile products. Exports of goods from the EU to Tajikistan amounted to €239 million. The EU exports mainly machinery, motors, vehicles, and pharmaceuticals to Tajikistan. In 2021, EU imports of goods from Uzbekistan amounted to €476 million, including industrial and agricultural products, while EU exports amounted to €2.29 billion[47]. Trade in goods between the EU and Kyrgyzstan increased to €337 million in 2021[48], of which €263 million were exports from the EU, including industrial products. In 2021, imports of goods from Turkmenistan to the EU amounted to €517 million, while exports from the EU amounted to €840 million, including industrial products. Given Turkmenistan’s large natural gas reserves, the Memorandum of Understanding on Energy Cooperation signed between the EU and Turkmenistan in 2008 provides a framework for the exchange of information on energy policy, discussions on diversifying transit routes, and the promotion of renewable energy and energy efficiency[49].

WTO membership for all Central Asian countries is a prerequisite for closer trade and investment relations with the EU. Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan gradually joined the WTO between 1998 and 2015, while Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are still non-members, the latter gaining observer status in 2020[50].

Among the priorities for the development of the EU-Central Asia partnership is also the consolidation of civil society and the enhancement of its role. Human rights violations by autocratic regimes in Central Asia remain a slippery slope in relations with Western democracies. Since 2019, the annual EU-CA Civil Society Forum has been held, providing a platform for civil society representatives from the two regions to promote partnerships.

The EU’s assistance programs in Central Asia are small, covering socially significant and politically neutral initiatives:

- SECCA: “The European Union’s program for Sustainable Energy Connectivity in Central Asia” is a €6.8 million program aimed at promoting a more sustainable energy mix in the CA region. The program aims to address climate change by optimizing energy efficiency and developing renewable energy.

- TEI ON DIGITAL CONNECTIVITY: This flagship program aims to develop the legal and regulatory environment for satellite communications, to create satellite communications operators (SatComs) in Central Asia with direct connection to the EU.

- TEI ON WATER, ENERGY AND CLIMATE CHANGE: The flagship program aims to promote sustainable management of water and energy resources, and boost investment in the energy transition in Central Asia.

- CACCR: “Central Asia COVID-19 Crisis Response Programme” is a €10.3 million program co-funded by the EU and WHO that helps mitigate the impact and control of the COVID-19 pandemic in the region, provides for the supply of vaccines, the establishment of a routine immunization system, and the digitalization of health systems.

Annex 3

EU—Central Asia Summit.

At the summit, the Central Asian countries indicated their expectation to cooperate with the EU in creating “efficient transport and logistics corridors to enter the EU market, with regard to new restrictions”[51]. They talked about the development of the Trans-Caspian multimodal route through the South Caucasus and Türkiye, which will be harmonized with the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T).

At the summit, each of the Central Asian countries made proposals for the development of relations with the EU. Kazakhstan has come up with an initiative to increase the supply of food and grain—currently, more than 5 million tons of wheat are exported to European countries per year. In addition, Kazakhstan may start exporting more than 100 types of engineering, metallurgy and chemical products worth about $1.5 billion. Uzbekistan offered Europe to join the development of regional tourism and expressed its readiness to supply agricultural products and textiles. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan are counting on the EU’s participation in joint projects on the use of water and energy resources and mineral processing.

[1] https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy-environment/news/eu-to-introduce-targets-for-raw-materials-self-sufficiency/

[2] https://www.dw.com/ru/redkozemelnye-metally-iz-kitaa-gde-frg-najdet-im-alternativu/a-63542878

[3] Ibid.

[4] https://www.dkz.gov.ua/files/2021_materials_vol_1_net.pdf

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-economy/3615996-v-ukraini-zoseredzeni-pokladi-22-z-30-korisnih-kopalin-kriticnih-dla-es-smigal.html

[8] https://gmk.center/ua/posts/dohid-z-vidhodiv-ukraina-mozhe-podvoiti-pererobku-ta-eksport-shlakiv/

[9] https://www.inastana.kz/news/3500542/bolee-30-mlrd-tonn-othodov-nakopilos-v-kazahstane-minekologii

[10] https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-ukraine-strategic-partnership-raw-materials-european-bank-reconstruction-and-development-will-2022-11-17_en

[11] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_22_6971

[12] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2019/06/17/central-asia-council-adopts-a-new-eu-strategy-for-the-region/

[13] https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/EU-Central%20Asia%20relations%20factsheet.pdf

[14] https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/central-asia%E2%80%99s-growing-importance-globally-and-eu_en

[15] https://akorda.kz/ru/prezidenty-kazahstana-i-evropeyskogo-soveta-proveli-brifing-dlya-predstaviteley-smi-2791614

[16] https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/central-asia%E2%80%99s-growing-importance-globally-and-eu_en

[17] https://www.commonspace.eu/news/eu-and-kazakhstan-strengthen-their-strategic-partnership-signing-agreement-raw-materials

[18] https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/central-asia%E2%80%99s-growing-importance-globally-and-eu_en

[19] https://www.statista.com/statistics/264781/countries-with-the-largest-uranium-reserves/

[20] https://world-nuclear.org/information-library/nuclear-fuel-cycle/mining-of-uranium/world-uranium-mining-production.aspx

[21] https://www.podrobno.uz/cat/economic/uran-obogashchaet-kak-kazakhstan-zanyal-pervoe-mesto-v-mire-po-dobyche-urana-i-pochemu-etot-opyt-vazh/

[22] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590332221006606

[23] Ibid.

[24] https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/business/article/2000230796/business-why-sgr-is-a-tiny-part-in-china-s-game-plan-to-become-superpower

[25] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590332221006606

[26] Ibid.

[27] https://tyzhden.ua/ukraina-v-chysli-23-derzhav-shcho-potrapliaiut-u-kytajsku-borhovu-pastku/

[28] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2590332221006606

[29] https://eurasianet.org/tajikistan-chinese-company-gets-gold-mine-in-return-for-power-plant

[30] https://www.worldometers.info/oil/#oil-reserves

[31] https://www.worldometers.info/gas/gas-reserves-by-country/

[32] https://www.fpri.org/article/2022/09/europes-wait-for-turkmen-natural-gas-continues/

[33] https://www.euractiv.com/section/energy/news/erdogan-backs-turkmen-gas-link-easing-dependence-on-russia/

[34] https://uainfo.org/blognews/1568365262-turkmenistan-kto-zainteresovan-v-sohranenii-deystvuyushchego.html

[35] https://caspiannews.com/news-detail/turkmenistan-to-double-natural-gas-exports-to-china-2022-10-17-1/

[36] https://turkmenportal.com/blog/51875/si-czinpin-podderzhal-stroitelstvo-chetvertoi-vetki-gazoprovoda-turkmenistankitai

[37] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_4547

[38] Ibid.

[39] https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/eu-china-relations-factsheet_en#:~:text=The%20EU’s%20approach%20towards%20China,China%20has%20shifted%20over%20time

[40] https://railexpoua.com/novyny/uchasnyky-tmtm-stvoriat-sp-serednii-korydor/

[41] https://newtimes.kz/ekonomika/158652-kazahstan-budet-eksportirovat-uran-v-obhod-rossii-smi

[42] https://cawamedia.wordpress.com/2022/04/15/mellan-korridoren-kommer-att-etablera-ett-samriskforetag-2023/

[43] https://zn.ua/ukr/WORLD/jes-maje-unikati-stvorennja-novikh-zalezhnostej-borel.html

[44] https://www.kmu.gov.ua/news/minfin-ukrayina-otrimala-600-mln-yevro-makrofinansovoyi-dopomogi-yes

[45] https://kz.kursiv.media/2022-03-04/chto-svyazyvaet-kazahstan-i-ukrainu/

[46] https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/raw-materials/areas-specific-interest/critical-raw-materials_en

[47] https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/isdb_results/factsheets/country/details_uzbekistan_en.pdf

[48] https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/EEAS-CA%20MINISTERIAL%20FACTSHEETS-2022-Kyrgyzstan.pdf

[49] https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/EEAS-CA%20MINISTERIAL%20FACTSHEETS-2022-Turkmenistan_31Oct.pdf

[50] https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/central-asia_en

[51] https://www.dw.com/ru/stroit-mosty-a-ne-steny-itogi-sammita-es-ca-v-astane/a-63580160

© Centre for Global Studies «Strategy ХХІ»

Author group:

Mykhailo Gonchar,

Oksana Ishchuk,

Serhii Lesniak

The information and views set out in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine.

Centre for Global Studies «Strategy ХХІ»

Shchekavytska str, 51 office 26

Kyiv, 04071, Ukraine

Е-mail: info@geostrategy.org.ua