INTERNAL POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT IN EU COUNTRIES ON THE EVE OF THE 2024 ELECTIONS AGAINST THE BACKGROUND OF ANTISYSTEMIC MOVEMENTS AND SECURITY CHALLENGES

Author:

Andrii Matviichuk

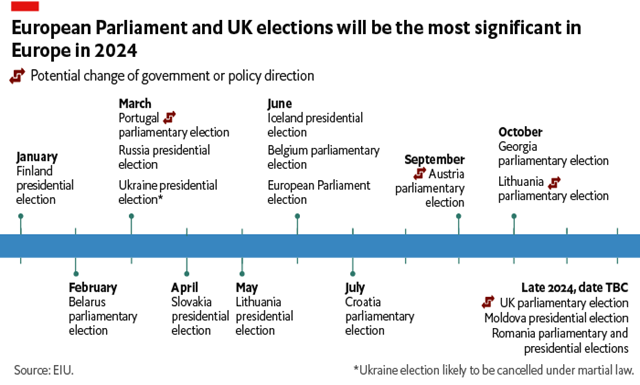

The next year is an extremely important political stage for our partners, as in 2024, a series of crucial political events will take place, including the elections for the President and Congress in the USA, as well as the elections to the European Parliament. Taking into account current anti-system movements and security challenges, these events may lead to fundamental changes in the political landscape. In this context, special attention should be given to the European Union, as the delay in the approval of financial and military assistance from the USA due to domestic political games and the risk of its reduction or cessation creates the necessity for the EU to review its budget priorities, especially concerning Ukraine. In light of this, the elections to the European Parliament will be of fundamental importance, as this body plays a crucial role in the funding and decision-making aspects of the EU.

The elections to the European Parliament will take place in June 2024. EU citizens will elect new members of the body, after which changes will occur in the European Commission – the member states of the Union will appoint key positions, including the new President of the European Commission and commissioners. Additionally, due to elections to the national parliaments of several Union members, changes are also possible in the composition of the Council of the EU and the Eurogroup, where representatives of new governments are likely to appear. Therefore, the primary way to predict the outcomes of the European elections is to observe political trends and results at the national level, which usually forecast the overall union-wide trends, as significant differences in the parties voted for in national elections and in the elections to the European Parliament are rare.

The results of the elections in 2023

This year’s elections were marked by interesting outcomes. For example, in Estonia, the victory of the “Reform Party” led by the current Prime Minister Kaja Kallas was one of the few triumphs of centrist parties in this calendar season. In Poland, the conservative party “Law and Justice,” despite winning the most votes, failed to form a new coalition. Instead, opposition pro-European centrist and left-wing forces formed the “Civic Coalition”, “New Left”, and “Third Way” coalition. Donald Tusk was elected as the new Prime Minister. In Spain, the social-democratic party “PSOE” managed to form a government again, but only with the support of the ultra-left party “Sumar”. The elections in Greece marked another victory for the conservative party “New Democracy”, which has been in power since 2019. In Finland, the National Coalition and the right-wing populist party “Finns” achieved success, forming a new government and leading to the resignation of the social-democratic Prime Minister Sanna Marin. In the Netherlands, the anti-European “Party for Freedom” won against the centrist competitor, the long-time Prime Minister Mark Rutte. In Slovakia, the victory was claimed by the anti-European populist “Party of Freedom” and “Direction – Social Democracy” (SMER-SD), surpassing the Liberal Party “Progressive Slovakia”.

The main trend in the 2023 elections is polarization between conservative and liberal forces, indicating a deep divide in European society. This may lead to increased political tension in the European Parliament and the need to reach compromises on crucial issues of European integration. The balance of power has clearly worsened for Ukraine, as at least two countries have elected forces skeptical of aiding our state. The consequences of Robert Fico’s party victory in Slovakia are already evident, as he promised to stop military assistance to Ukraine, although Slovak companies continue to fulfill defense orders for Kyiv paid by other states. Moreover, the Slovak government is not doing enough to unlock the border blocked by Slovak carriers. The victory of populists in the Netherlands potentially threatens the country’s participation in the aviation coalition for our country, although the formation of their coalition government is still pending.

Portugal will hold extraordinary elections in March, where under current circumstances, the far-right party “Chega” has the highest chances for the first time in a long time to form the next government, replacing the social-democratic one. In Belgium, according to recent polls, the anti-immigrant far-right force “Flemish Interest” could receive up to 23% of the votes in Flanders, potentially making it the largest party both in the region and in the country as a whole. In Austria, the ruling “Freedom Party of Austria” is likely to succeed as a potentially major party in parliament, unlikely to change Austrian politics.

According to trends and survey results, right-wing and populist parties will gain popularity across Europe in 2024, indicating a certain crisis of ideas within the continent. Asserting an absolute victory for right-wing forces is premature, considering that it is unknown what coalitions will be formed. As demonstrated by the history of Polish elections, winning elections does not always guarantee the formation of a coalition. However, in light of recent events in Italy and Sweden, where broad coalitions involving the far-right came to power, it can be assumed that such a trend will continue in 2024.

Elections to the European Parliament

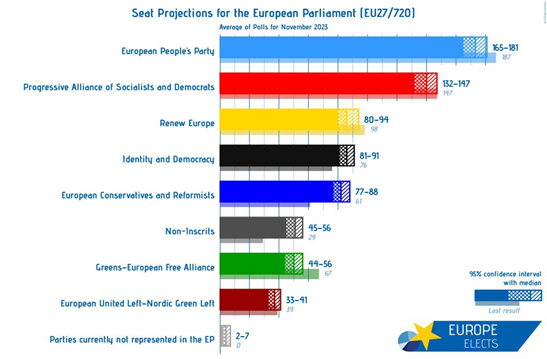

From the latest elections to the European Parliament, quite important changes have occurred, starting from the COVID-19 pandemic and ending with the war in Ukraine. Recent public opinion polls in the 27 EU member countries predict the loss of seats in the European Parliament for the following groups:

- The European People’s Party (EPP) will have 170-175 seats instead of the current 176.

- The Social Democrats (S&D) will have 142-138 instead of 144.

- The Liberal Renew Group will decrease from 101 to 90-84 seats.

- The Greens will have only 44-41 seats from the current 72.

- The Left will have 30-36 out of the current 37 seats.

Among the groups that, on the contrary, can improve their results:

- The Eurosceptic far-right (ID) will increase the number of seats from 60 to 84-89.

- The Conservative (ECR) will gain 78-79 seats from the current 66.

The trend of decreasing the share of votes for centrist groups EPP, S&D, and Renew, observed since 2009, is likely to continue in the upcoming elections to the European Parliament. The two largest of them, EPP and S&D, relying on polls, will have only up to 43%, and only all three centrist forces together can secure a majority, or 56%. Overall, the majority of seats will be neither to the left nor to the right in the party spectrum – current polls suggest that the European Parliament will be more fragmented and unpredictable. It is expected that the far-left and especially the far-right will be able to strengthen their positions at the expense of the center.

Possible scenarios of coalitions in the European Parliament

The first scenario is the preservation of a kind of sanitary cordon, supported at least by the EPP regarding ID and Renew regarding ECR. In this case, the coalition will consist of EPP-SD-Renew. For Ukraine, this is the best balance of forces that will contribute to the continuation of integration and obtaining financing, as our country already has good relations with the majority of parliamentarians. Under these conditions, Ursula von der Leyen will likely remain in her position, which also aligns with Ukraine’s interests.

In the other two scenarios, center-right parties engage in ongoing cooperation with either all or partially radical right parties. So, the second option is a national-liberal coalition RE-EPP-CRE, modeled after the current cabinet of ministers in Sweden led by Ulf Kristersson. In the “Kristersson scenario”, the ID group remains excluded from any formal or semi-official cooperation between parties, thereby reducing reputational risks for center-right parties. This is the least likely course of events but not the worst for Ukraine. Under this scenario, EU policy will shift to the right, making it much more difficult for our country to receive military aid. However, at the same time, most right-wing politicians strongly oppose Russia, so the strategy of countering Russia is likely to remain at the same level.

The third scenario is a right-wing alliance of EPP, CRE, and ID groups, similar to the Meloni government model. In these conditions, center-right and far-right parties form a majority together, involving a limited number of liberal and independent members. This is the worst scenario for Ukraine for several reasons. Firstly, the rise of ID to power will increase the influence of right-wing populist parties in Europe overall since a certain sanitary cordon that has always existed in the European Parliament will be violated. Many politicians within the Union will find it much easier, through deception and manipulation, to enter the government of the European Parliament through far-right and populist parties. Secondly, some members of ID adhere to a fairly favorable attitude towards Russia and advocate for ending the war even on unfavorable terms for Ukraine and against our country’s accession to the EU. So, even if they fail to suspend integration processes, they can at least slow them down.

The following issues are also expected to receive greater attention from the new parliament:

- Stricter migration policies;

- Tax legislation, workers’ rights, and profits;

- Capital markets, health, economic security;

- Energy and climate policy;

- Geopolitics: China, USA, Ukraine, Russia, Africa;

- EU competitiveness. Industry, infrastructure, regulatory acts, workforce skills, investments, technology, trade, innovation, economy;

- Security strategy, defense, cybersecurity (Cyber Resilience Act), data protection, telecommunications;

- EU expansion (Western Balkans);

- Artificial intelligence rules.

The trends of the EU in the year 2024

Youth decides

There is an assumption that young voters, as a rule, are more progressive throughout the EU from Sweden to Spain; however, at the same time, radical or conservative parties increasingly attract the votes of the younger generations in several recent elections in EU countries.

If all those who voted in the elections in the Netherlands were under 35 years old, Geert Wilders, the far-right populist whose Party for Freedom (PVV) shocked Europe by winning the most seats in parliament, would have gained an even more significant advantage. In the second round of last year’s presidential elections in France, Marine Le Pen received 39% of the votes from people aged 18-24 and 49% from people aged 25-34. Before the elections in Italy last year, Giorgia Meloni’s “Brothers of Italy” were the most popular party among those under 35.

European analysts explain that ultra-right parties are not the best or even the second choice for young voters throughout Europe. However, the modern youth is characterized by a sense of economic insecurity and distrust of the future. As ultra-right parties increasingly offer young and often charismatic politicians who speak their language and address internal issues that concern young voters, they tend to vote for them. Overall, this trend is most pronounced in countries such as Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark.

However, it is erroneous to claim that young people always vote for ultra-right forces; a reverse example could be parliamentary elections in Poland, where the turnout was 74.3%, a record exceeding even the 1989 figure. The key to this was the mobilization of youth, historically the most unengaged demographic group. Almost 69% of the population under 30 came out to vote, not necessarily for the opposition but against the ruling party that had been in power for 8 years. So, the trend is that forces capable of mobilizing youth in elections are more likely to win, and currently, these are the right-conservative circles of Europe.

The right turn in Europe

Recent political events confirm the growth and consolidation of conservative right-wing European parties, a trend that began in 2015 in Poland and has since steadily increased.

The recent shocking victory of populist Geert Wilders in the November elections in the Netherlands was the latest in a series of victories for European far-right parties. During the current five-year term of the European Parliament, far-right parties in Italy, Finland, and Sweden have celebrated significant triumphs in elections and are rapidly growing in Germany, France, and Austria.

Far-right parties hold power or are affiliated with it in Sweden, Finland, Latvia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Italy. The Austrian Freedom Party dominates the country’s political landscape, and the “Alternative for Germany” is the second-largest party in the state according to polls. Meanwhile, in France, President Emmanuel Macron’s policies and the inability of the left to offer a worthy alternative gradually strengthen the National Rally party.

European far-right political forces have reached a record level just months before the EU elections. According to a new forecast for seats in the European Parliament from Europe Elects, if they were held today, anti-European far-right political parties united under the banner of the “Identity and Democracy” (ID) group in the EU Parliament would secure 87-91 out of 705 seats (currently, they hold 60). ID consists of parties such as the nationalist National Rally of Marine Le Pen (RN), the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), and Matteo Salvini’s League, which is already a coalition partner in Italy.

Traditional right-wing parties, facing elections, increasingly align with the far-right rather than with the left and centrists, as evidenced by the results of formed coalitions in Europe over the last 2 years. For example, in Italy, the center-right parties League and Forward, Italy formed a coalition with the far-right Brothers of Italy. A similar situation was observed in Sweden and Finland. European Parliament spokesperson Jaume Duch stated that a shift to the right in the composition of the parliament does not necessarily weaken the role of the EU, despite the eurosceptic positions of some far-right forces.

“Parties that were previously practically in favor of leaving the European Union are now making other proposals that no longer involve a breakup but rather prioritize the need for changes in the EU,” explained Duch.

It is important to understand that there are significant differences in form and content among right-wing parties: the center-right New Democracy in Greece is very different from the Alternative for Germany; the National Front in France is not the same as the Brothers of Italy. However, ideological trends and political priorities in global European politics, changing due to accumulated problems within the EU, can be identified. One can conclude that the previously popular Christian Democrats and liberal right are losing ground to national populism and the resurgence of continental conservatism.

The decline of the “sanitary cordon”

The concept of the “sanitary cordon” emerged in Belgium in the late 1980s in response to the rise of the far-right party Vlaams Blok BE (now Vlaams BelangBE) in Flanders. Confronted with the nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric of VB BE, the centrist parties of Belgium decided to establish a “sanitary cordon” around it. The main idea was to refuse any cooperation, coalition, or agreement with VB BE, which was considered a threat to democracy and the fundamental values of Belgium. Later, this term was applied to other political systems where similar far-right parties gained popularity. At the European level, the “cordon sanitaire” strategy of isolating far-right parties seems to be waning. Recent political trends in several European countries show an increasing willingness of centrist parties to cooperate and even govern with far-right allies.

A year before the 2024 European elections, the sanitary cordon remains in effect in only eleven of the 27 EU member countries. Among them are founding countries Belgium, Luxembourg, France, and Germany on one side, and Ireland, the Czech Republic, Romania, Slovenia, Croatia, Malta, and Cyprus on the other. However, no right-wing nationalist party is represented in the national parliaments of Ireland and Malta. In all other EU member countries, governments with the participation of right-wing nationalist parties have been formed at the national or regional levels since the 1990s.

Green and red lose colors

Social democracy is retreating everywhere, just like the greens. Only five out of the 27 member countries of the European Union are currently under the leadership of social democrats: Portugal, Slovenia, Malta, Denmark, and Germany. The previous electoral season was the most successful for green parties in Europe, as they had unique opportunities to resist polarization and stabilize the political center. There was hope that the green wave would suppress the growing populist tide.

However, in recent years, the greens have failed in elections in Luxembourg, Finland, and Switzerland, and the most powerful representatives of the “Green Party of Germany” suffered a devastating defeat in regional elections. Today, “Alternative for Germany” is surpassing its ideological competitors at the national level.

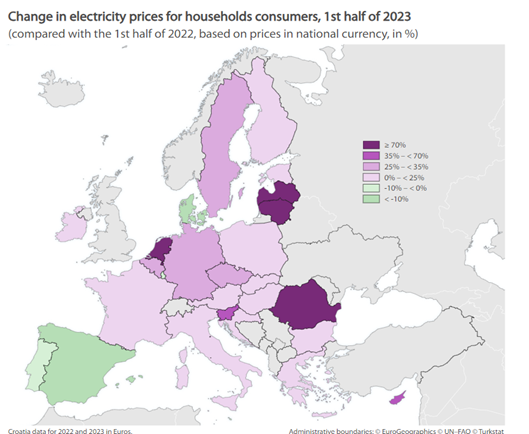

Support for greens and socialists is declining across Europe due to concerns about the costs of climate policy following the increase in prices for municipal services, which occurred due to sanctions against one of the main gas suppliers in Russia. For example, in the first half of 2023, energy prices surged the most in Latvia and Romania – by 139% and 134%, respectively. Although Green policy remains very interesting and relevant in Europe, its main lobbyists – the European Free Alliance – are likely to lose the most seats in the new European Parliament.

The crisis of centrism and the rise of populism

Unlike the tendency towards the growth of right-wing conservatives, the forces of the political center in Europe are experiencing uneasy times. Four national parties with the most seats in the Renew Group are grappling with a decline in their ratings, which has sometimes been abrupt.

In the European structure, populist parties are closely linked to Euroscepticism. In 2023, after the Covid-19 pandemic and its restrictions, as well as the pressure of refugees and inflation, there has been a shift to the right in Europe with the rise of right-wing coalitions with far-right parties worldwide. The next parliament is likely to advocate for a more market-oriented approach.

Security

Little any theme became so relevant for the EU in recent years, both in the context of military defense and digital security. The main challenge for the first category in 2024 is that the bloc needs to deal with several crises in neighboring regions simultaneously: Ukraine, Israel, and Nagorno-Karabakh. However, the European Union will also have to respond to other unforeseen crises, such as internal security.

Yes, for example, in France, where the largest number of Jews and Muslims in Western Europe reside, there have been over 850 anti-Semitic acts after the attack by the Islamist group HAMAS on Israel. Unlike a series of terrorist attacks organized by the “Islamic State” throughout Europe in 2015 and 2016, today’s threat comes from “isolated individuals” from Europe, not from those who returned from Iraq or Syria with the intention of striking.

Today, Europe suffers from internal threats, such as radical Islamic groups and Russia’s permanent aggression, manifested in constant threats, cyber attacks, and possible sabotage. Lately, officials from Poland and Germany have increasingly called on the EU to militarize and start building up the defense industry in view of a possible confrontation with Russia in the next 3-10 years.

Considering the limitation of military resources, as revealed during the war in Ukraine, the European Union needs to rethink its military policy and build up its own military-industrial complex. However, although a strong material foundation is important for European security and defense, it cannot be taken for granted if Eurosceptic groups demonstrate strong results in the new parliament.

As mentioned earlier, security in the modern world is not just tanks and missiles but also the digital dimension. Unfortunately, cybersecurity in the EU is still “below industry standards” and “does not fully correspond to the level of threat” posed by hackers. The IT department of the European Parliament presented a report to the group of key members of the body, stating that attacks on the parliament have become more numerous and sophisticated since the 2019 elections. The document establishes that the most vulnerable to attackers are cyber attacks on voting systems and those targeting major political debates at the national and EU levels, as well as the parliamentary election process and influencing public opinion on specific candidates through disinformation. These challenges are exacerbated by geopolitical instability and associated political activism.

Several incidents have already demonstrated that foreign states, especially Russia, have intensified their efforts to undermine European policy. Last year, the parliament’s website faced a “complex” cyber attack that led to disruptions in its operation immediately after deputies voted to recognize the Russian Federation as a state sponsor of terrorism.

The number of cyber attacks on EU institutions is “sharply increasing”, as noted in the report of November 29, and the Union must prepare to confront such threats, which politicians, parliaments, and governments across Europe have faced in recent years.

Conclusions

After the elections next year, the majority in the European Parliament will become even less clear. The same applies to representatives of power in the EU Council and the Euro Council. The change in the prevailing majority will increasingly influence the processes of political decision-making in European institutions. Overall, in the new five-year mandate of the Commission, the emergence of certain adjustments in the general political agenda is expected. For example, the budget of the European Union will be under pressure, affecting policies on agriculture, structural funds, and defense. Environmental and digital regulations will remain priorities, exerting pressure to slow down the pace of reforms, including attempts to reconcile the EU’s “Green Deal” with economic competitiveness. More restrictive policies can be expected in asylum and border control issues.

Europe with a new parliament, relying on the results of the elections in the USA, will build a new security policy relying on its own strength and expanding its military capabilities.

Due to the gradual rightward shift in Europe, Ukraine will need to build a new, more pragmatic international policy. The conditional “romantic period of relations” will end. It is very likely that it will be much more difficult to coordinate decisions important for our state. However, despite this, with proper work in this direction, the EU will be able to remain a reliable partner for Ukraine and provide significant economic and military assistance.

© Think Tank ADASTRA

Author:

Andrii Matviichuk

The information and views set out in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine.

Think Tank ADASTRA

Phone: +380954592954

E-mail: adastra@adastra.org.ua