|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

THE IMPACT OF INTERNATIONAL SANCTIONS ON RUSSIAN POLITICS AND ECONOMY IN 2024-2025

Author:

Bohdan Bernatskyi, Max Weber Fellow, European University Institute (EUI)

Sanctions have a threefold purpose: (1) to change the behavior of the subject; (2) to punish or harm the sanctioned subject; (3) to signal a violation of international law norms. However, the question of whether sanctions can truly fulfill this threefold purpose is quite debatable in contemporary literature[1].

On one hand, sanctions are considered one of the most effective tools for combating violations of international law norms. Article 41 of the UN Charter states that the UN Security Council has the right to apply non-military means to prevent and eliminate threats to peace and security[2]. In addition to UN Security Council sanctions, there are sanctions imposed by countries unilaterally (or by a group of states). In literature, these are called unilateral sanctions. This practice is well-established for EU countries, the USA, and the G7 in general. For example, the EU has provided for the possibility of imposing sanctions (restrictive measures) in its founding documents, particularly in Article 215 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union[3].

On the other hand, sanctions are not always effective in achieving their goals, especially when it comes to changing the behavior of the sanctioned subject. Moreover, since the 20th century, i.e., since the emergence of sanctions in their modern understanding, the effectiveness of this tool has depended on a number of factors, including the imposing subject; the subject on which they are imposed; and the political and economic situation in the world[4].

In 2014, Russia invaded and occupied Crimea and the eastern regions of Ukraine. As a result, the EU and the US imposed the first sanctions against the Russian Federation. From 2014 to January 2022, the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) added approximately 445 individuals, legal entities, vessels, and aircraft to the list of sanctioned subjects[5]. At the same time, the EU imposed sanctions on at least 177 individuals and 48 legal entities[6].

Since 2014, the EU and the US have imposed three types of sanctions against Russia. The first type was sanctions on individuals and legal entities. The following restrictive measures were imposed on persons whose names were added to a special list (in the US, it is called the SDN list): (1) their assets were frozen; (2) they were banned from traveling to the countries. The second type was sectoral sanctions. The US, EU, and other countries imposed sanctions on the financial sector, energy sector, and military sector. In the US, this included, in particular, a ban on transactions, provision of financing, or other settlement of new debt with a maturity of more than 30 days[7]. The third type was a trade embargo and new investments regarding Crimea temporarily occupied by Russia.

As time has shown, the sanctions were inconsistent and did not fully achieve their goals. Firstly, Russia’s policy towards Ukraine, its sovereignty, and territorial integrity did not change. On the contrary, over 8 years, Russia increased its military power; and on February 24, 2022, it launched a full-scale invasion. Secondly, according to the assessment of the impact of imposed sanctions during 2014-January 2022 on Russia’s economy, the damage inflicted was relatively small. The report from January 2022, prepared by the Congressional Research Service, repeatedly noted that the scale of damage caused by sanctions was modest compared to the negative consequences caused by other world events. Russia’s economy suffered more from Covid-19 than from sanctions[8].

Sanctions after February 2022

In February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine’s territory. These actions triggered an unprecedented wave of sanctions against Russia from the US, EU, and several other countries. De facto, these sanctions became the most extensive sanction measures outside the UN Security Council system, with G7 and the EU acting as the main sanction players. The overall sanctions infrastructure, built since 2014, underwent dramatic changes. Firstly, the sanctions that operated from 2014 to 2022 can be characterized as “signaling”, imposed to demonstrate the illegality of the occupation of the Autonomous Republic of Crimea and the city of Sevastopol by the Russian Federation. The restrictions themselves concerned a small circle of individuals, did not touch Russia’s top political and military leadership, and simultaneously, no tools were created for joint monitoring of sanction restrictions. Moreover, sanctions adopted under the “misappropriation” regime were successfully challenged[9].

In contrast, the sanction restrictions and prohibitions applied after 2022 aim not so much to signal Russia’s violation of international law norms, as to damage the Kremlin’s military-industrial complex and increase its costs of waging an aggressive war. Secondly, over a short period, a number of formal and informal organizations were formed at the G7 and EU levels, aimed at coordinating sanction policy and monitoring the implementation of sanction restrictions. Among the new elements of the sanction infrastructure, the following can be noted:

- Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Task Force:

The task force was created at the initiative of the EU, G7 countries, and Australia. In a joint statement, participating countries determined that they commit to accumulating resources and working together to “take all available legal measures to find, freeze, block, and, where appropriate, confiscate the assets of individuals sanctioned in connection with Russia’s deliberate, unjust actions, unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, and the ongoing aggression of the Russian regime[10]“. As of March 2023, the Task Force successfully froze or blocked Russian assets worth $58 billion USD[11].

- David O’Sullivan as EU Special Envoy for Sanctions Implementation:

In December 2022, the European Union decided to create the position of EU Special Envoy for Sanctions Implementation to ensure discussions with third countries on the issue of circumventing restrictive measures imposed in connection with the war started by Russia against Ukraine[12].

- Yermak-McFaul International Sanctions Group:

An international group consisting of experts on sanctions against Russia was formed to “provide a comprehensive list of possible additional economic and political measures to strengthen US, European, and global sanctions against Russia and Belarus to end Russia’s war against Ukraine as soon as possible[13]“.

- G7 platform for announcing joint sanctions decisions:

Since 2022, with the beginning of the full-scale invasion, G7 countries in their statements on support for Ukraine recognized their obligation to continue applying coordinated sanctions against Russia[14]. For example, during the G7 summit in May 2023, the US, Canada, and the UK announced new sanctions against a number of individuals and legal entities[15].

As of July 2024, the EU has adopted 14 sanctions packages[16], while the United Kingdom’s sanctions largely duplicate the approaches used by the EU. The US, on the other hand, does not adopt sanctions on a “package” principle, but rather almost monthly, expanding various personal and sectoral sanctions programs.

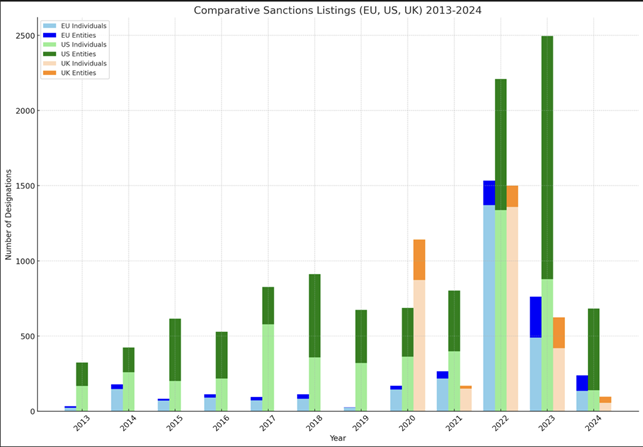

The scope of personal sanctions imposed by the US, United Kingdom, and EU each year (information taken from https://sanctions-finder.com/ and generated using ChatGPT).

More than 50% of the sanctions imposed after 2022 relate to Russia and Belarus for waging an aggressive war against Ukraine.

Sectoral and personal sanctions programs against Russia and Belarus (as of April 2024)

| Sanctions Programs | No | ||||||||

| EU | UKR (2157) | RUS (648) | BLR (302) | 3107 | |||||

| EU Sect. | UKR (4) | RUS (23) | BLR (17) | 44 | |||||

| USA | EO14024 (3864) | EO13662 (309) | EO13661 (189) | EO13660 (154) | EO14038 (142) | EO13685 (96) | BELARUS (73) | CAATSA (54) | 4869 |

| USA Sect. | EO14038 (9) | EO14024 (6) | EO13662 (3) | EO13685 (3) | 21 | ||||

Economic Dimension of Sanctions

An important initial caution for assessing the impact of sanctions on the economy should be the position that no model can fully reveal whether sanctions are effective or not. It is impossible to reliably and objectively assess the impact of sanctions on the economy in isolation, as sanctions are part of an overall policy to counter aggression, which also involves third countries. Given this, any economic and financial models can serve only as an additional indicator for assessing the effectiveness or impact of sanctions on the aggressor state. It can also be noted that until 2022, sanctions did not cause any tangible harm or losses to the Russian Federation, and the Russian economy showed steady growth[17]. The previous thesis is also confirmed by a 2016 study by the Office of the Chief Economist (OCE)[18]. At that time, the analysis showed that the GDP decline and ruble devaluation were caused primarily by the fall in global oil prices, while sanctions played only a secondary role[19].

Current Sanctions[20]

- Sanctions against Russia are targeted in nature and their scope can hardly be characterized as a comprehensive economic embargo. Trade in goods and services between EU countries and Russia continues, although it has significantly decreased.

- Financial sanctions: disconnection of some banks from the SWIFT system, prohibition for foreign banks to conduct operations with designated Russian firms and banks, freezing of assets of the Central Bank of Russia[21]. As of 2022, approximately ⅔ of Russia’s banking system, measured in assets, lost access to American and European banking systems[22].

- Export controls on goods and technologies necessary for the military, aerospace, and maritime sectors, dual-use goods[23]. Additionally, it is prohibited to import luxury items into Russia.

- Import bans: energy embargo on crude and refined oil and other products, including Russian diamonds[24].

- G7 limited the prices of crude oil, setting $60 per barrel from December 2022. In February 2023, G7, EU, and Australia limited prices on diesel fuel and other petroleum products[25].

- Sanctions on individuals and legal entities involved in the war. Restrictive measures for such persons include asset freezing, travel bans to countries that have imposed sanctions.

- Indirect sanctions: large companies are leaving the Russian market under societal pressure, i.e., under pressure from consumers and counterparties[26]. In Ukraine, media publish lists of companies that have not yet left the Russian market. This list influences Ukrainian consumer choices when buying goods.

Energy Sector

The energy sector is the central source of Russia’s income. The Russian economy (GDP) is mainly formed by excess profits from energy resources (crude oil, natural gas, coal). Oil and gas revenues, which usually account for about 40% of federal revenues, jumped to 50% in the second quarter of 2022[27]. At the same time, the revenues of Gazprom, one of Russia’s largest oil and gas companies, are gradually decreasing. In 2023, the company’s losses amounted to 7 billion US dollars. This indicator was obtained for the first time in 20 years[28].

Natural Gas

Before the full-scale invasion, Russia exported 68 billion cubic meters of gas to the EU[29]. Since 2022, bans on importing energy resources to EU countries have been imposed. As a result, the volume of gas exports from Russia, excluding imports of liquefied natural gas, fell from 40% in 2021 to 8% in 2023[30]. Due to the loss of a significant share in the European market, Russia is trying to fill the losses through the Asian market, particularly the Chinese market has become very attractive for Russia. However, China is not rushing to strengthen its cooperation with Russia in the energy sector.

In 2019, Russia began supplying gas to China through the Power of Siberia pipeline. The maximum volume of gas exports to China reaches 38 billion cubic meters[31]. That is, today the volume of gas supply to China is at least twice less than the volume that went to the EU before the full-scale invasion.

As a result, the Russian government decided to promote the idea of building an additional Power of Siberia-2 pipeline, which should export an additional 50 billion cubic meters of gas to China annually[32]. In this way, Russia plans to cover the losses incurred due to the EU’s refusal to use their gas. At the same time, China is behaving quite cautiously on this issue. Firstly, the agreement on the construction of such a pipeline has not yet been signed[33]. In 2023, Putin and Alexander Novak, the former Minister of Energy of Russia, noted that China and Russia were already at the last stage of agreements and that everything would be signed by the end of the year[34]. Instead, Chinese President Xi Jinping said nothing about the pipeline after meeting with Putin in 2023[35]. Secondly, China is interested in diversifying gas suppliers. This country has long-term contracts with Qatar, the USA, and other countries[36].

There is another point that indicates Russia’s inability to achieve the same level of income it received from supplying gas to the EU. According to media reports, even an increase in natural gas exports to China will prove less profitable than supplying to the European Union before the full-scale invasion[37]. As of 2024, natural gas supplied to China is approximately 28% cheaper than gas supplied to the EU[38].

China, Central Asian countries, and the Caucasus act as alternative consumers or transit hubs for Russian energy products. At the same time, China, for example, is not rushing to strengthen cooperation with Russia. Moreover, the price of gas exported to China is lower than the cost at which the EU bought. And even increasing the volume of gas supply to China will not be able to bring the profits that Russia received from the EU before the full-scale invasion. In fact, over the next 10 years, Russian energy sector companies will not achieve pre-war income received from gas exports.

Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG)

The flow of income from the EU to Russia for LNG sales will remain continuous in 2024 and 2025 due to the unpreparedness of European countries to impose an embargo on this type of Russian gas. LNG is one of the main sources of income for Russia. Moreover, the government plans to increase the profit tax rate for LNG production from 20% to 32% in 2023-2025[39]. Thus, Russia will be able to increase revenues to the state budget, which will finance the war in Ukraine.

According to “INTERFAX.RU”, in 2022 Russia directed over 76% of Yamal LNG to the EU[40]. In the first seven months of 2023, Russia exported 40% more liquefied gas by tankers to European countries than in the same period in 2021[41]. Although the supply volume is small compared to pipeline gas, such exports brought Russia approximately 5.29 billion euros ($5.78 billion euros) in 2023.

In the short term, the EU will continue to spend billions of euros on purchasing Russian LNG[42]. In June 2024, the EU adopted the 14th package of sanctions, which still did not impose an embargo on LNG. However, the sanctions introduced a ban on the resale and transshipment of Russian LNG in EU ports and waters[43]. A ban on investing, providing goods, technologies, and services for completing the construction of LNG terminals in the Arctic and Baltic regions was also introduced[44]. Due to an adaptation period of 9 months (until March 2025), the effectiveness of such sanctions can only be seen after 2025.

Oil

Before the imposition of sanctions in 2022, Europe accounted for more than 60% of Russian oil exports[45]. After the full-scale invasion, this indicator significantly decreased. Due to the EU embargo on Russian oil, companies have reconfigured to the Asian market to compensate for lost European volumes. Unfortunately, unlike with gas, Russia has succeeded in its actions. According to a Kpler analyst, Asia saved the Russian oil market: “instead of further falling, Russia approached the pre-pandemic level[46]“.

After the full-scale invasion, Russia lowered oil prices to attract buyers from Asia. In 2022, the price per barrel was $48-50[47]. As of April 2024, the price for Urals crude oil was approximately $68, while Brent oil cost an average of $83 per barrel. Discounts helped quickly reconfigure to the Asian and African markets. In 2023, there was a 56% jump in supplies to Asia and a 144% increase in oil sales to Africa[48]. In 2023, the annual increase in oil purchases by Asia and Africa became record-breaking[49].

At the same time, the EU embargo and discounts have led to Russia losing approximately $126 billion in oil export revenues since 2022 due to the invasion[50]. According to the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), in the first quarter of 2023, losses reached 180 million euros per day; and then decreased to 50-90 million euros per day in the second and third quarters of the year. Thus, due to growing demand among Asian and African buyers, Russia’s oil production volumes have hardly changed from pre-war years. What has changed is that Russian oil exports to those markets do not provide the profit that existed before the embargo and price reduction by G7 countries. The level of losses is growing annually.

Furthermore, an Atlantic Council study states that transportation to India and China is more time-consuming and expensive compared to oil transportation to the EU. The study’s author calculated that the price of maritime oil transportation from Novorossiysk or Primorsk to India ranges from 10 to 15 dollars per barrel[51].

Another important point that could potentially affect the volume and income level from oil production is technology. Due to imposed sanctions, many European companies with necessary technologies have left the Russian market. As a result, the oil industry will gradually lose the ability to use technically complex resources. According to Bloomberg calculations, if the dynamics of sanctions do not change, by the end of the decade, production will decrease to 8.2 million barrels per day, compared to about 11 million barrels as of April 2023[52].

Price Cap on Russian Oil

In 2022, the G7 and EU set a price cap on Russian seaborne crude oil at $60 per barrel. These countries prohibited providing services for oil supplies exceeding the maximum set price, including trade and commodity brokerage, financing, delivery, insurance, as well as protection and compensation, labeling, and customs brokerage[53].

The oil price cap has not yet yielded positive results. In the last quarter of 2023, over 95% of all Russian seaborne crude oil exports were exported at prices exceeding $60. Meanwhile, about 30% of all exported oil was delivered with the involvement of G7/EU companies[54].

Russian companies are constantly looking for ways to circumvent the restrictions. Some legal entities submit documents with false data[55]. There is a possibility that legal entities with connections to Russia may submit falsified data to the authorities responsible for enforcing the rules regarding the price cap on Russian oil.

Additionally, Russia actively uses a shadow fleet. The shadow fleet, i.e., ships not owned, managed, or insured by G7 and EU[56], is a threat to the effectiveness of sanctions. This way, Russia bypasses restrictions and generates new revenues to maintain macroeconomic indicators at an appropriate level.

From December 5, 2022, to November 5, 2023, approximately 38% of Russian oil was exported using “shadow” tankers[57]. According to the KSE Institute, 228 “shadow” tankers left Russian ports in April 2024, two of which used the ship-to-ship method[58]. Meanwhile, OFAC has sanctioned only 41 ships, of which only 32 have completely ceased their activities (data as of May 2024)[59]. Imposing sanctions on ships not only helps reduce Russia’s level of circumvention of restrictions but also harms the Russian budget. The latter is explained by the fact that the government buys ships to replace those that have been sanctioned. Although Russia mainly buys old tankers (most of them over 15 years old)[60], their value is estimated at millions of dollars. Since spring 2022, Russia has purchased over 250 tankers; the current value of the acquired fleet is approaching $9 billion[61].

The ineffectiveness of the imposed price cap on Russian oil is also explained by the low level of preparedness of G7/EU countries in ensuring compliance with oil price restrictions. Monitoring transactions requires thousands of new employees and constant cooperation among all countries[62]. There are many ways to improve the effectiveness of sanctions, but they have not yet been implemented. In particular, a system for verifying the presence of proper insurance has not been adopted, which would help prevent improperly insured Russian tankers from passing through the waters of the respective country[63].

The KSE Institute forecasts that oil revenues in Russia will reach $172 billion and $142 billion in 2024 and 2025, respectively. However, if sanctions are not adhered to, Russia’s oil revenues could increase, reaching $194 billion in 2024 and $188 billion in 2025[64]. Since practice shows that the oil price cap is not effective, at least in the short term, it is impossible to speak about the implementation of the first option.

Financial Sector

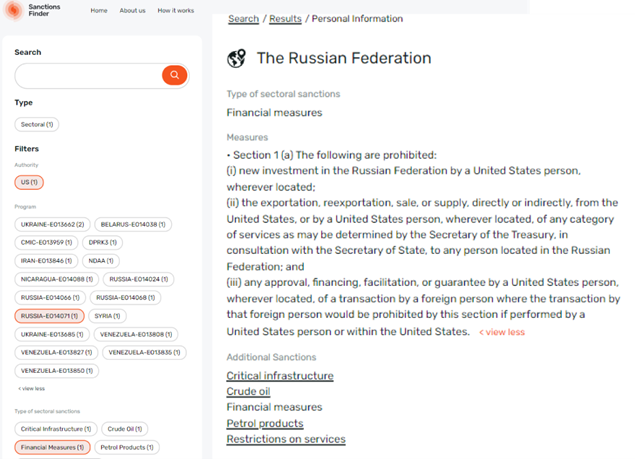

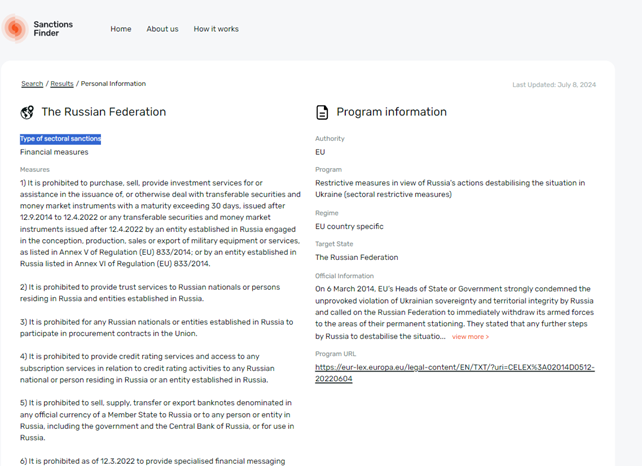

Economic sanctions play an important role in reducing material inflows to the Russian federal budget. After the full-scale invasion, America and the EU changed their vision, which they had adhered to during 2014-2022, regarding the future fate of Russia’s financial sector. Sectoral sanctions, namely sanctions on the Russian financial sector after 2022, are proof that America and the EU aim to undermine the Russian economy. For example, below are the financial restrictions implemented by the US in 2022 through Executive Order 14071. This act is just one of the sectoral sanction programs implemented by the US in response to Russia’s unprovoked war against Ukraine. In 2022, Europe, not lagging behind the US, also expanded financial restrictions. The list consists of 19 restrictions, a full list of which is presented on Sanctions Finder.

Since 2022, the US has not only frozen assets of the largest Russian financial institutions, including the assets of the Central Bank of Russia worth about $250 billion[65], but also cut the country off from access to the global financial system. Sanctioned banks and other financial institutions lost the ability to conduct international operations. As a result, a large number of transactions were/are being blocked by countries, including those that are currently helping to circumvent sanctions (China, Turkey, Iran). Russia is gradually losing the ability to receive payment for goods it exports or imports.

After the full-scale invasion, countries cut off Russian financial institutions from SWIFT. That was an unprecedented action against Russia by the West since 2014. In 2022, the US and EU disconnected Sberbank, Russia’s largest bank and one of the main channels for gas and oil payments, from SWIFT[66]. The uniqueness of this type of sanction lies in the fact that, unlike sanctions on gas and oil, Russia is unable to find an alternative to the international SWIFT payment messaging system. It is unique in nature as it unites about 11,000 financial institutions in more than 200 countries worldwide[67].

Prior to the full-scale invasion, Russia began developing its own SWIFT analogue called the System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS)[68]. As of 2022, the system united 400 national financial institutions in Russia and approximately 50 other legal entities outside the country[69]. The latest EU sanctions package, adopted at the end of June 2024, prohibits European banks from participating in the SPFS system[70]. Additionally, the EU has identified a list of non-Russian banks that are part of the system and imposed a ban on European operators doing business with them[71].

Disconnection from SWIFT is only one component that undermines the effectiveness of international transfers. The most important part of economic sanctions is the imposition of direct restrictions on Russian financial institutions. Firstly, sanctions on Russian banks provided grounds for freezing assets with the prospect of their confiscation (the latter issue is still under discussion). Furthermore, these banks are subject to restrictions on correspondent relationships. This means that banks in the US, EU, UK, and other countries block transactions initiated or conducted by sanctioned entities. In addition to limiting correspondent relationships, countries are implementing so-called full blocking sanctions. In 2022, the US imposed this type of sanction on Sberbank, which, as mentioned earlier, is Russia’s largest bank[72]. The United States Deputy Secretary of the Treasury explained that full blocking sanctions allow not only blocking the company’s assets directly (in our example, Sberbank) but also freezing the assets of all entities 50% or more owned by the sanctioned person[73]. Thus, OFAC added to the sanctions list not only Sberbank itself but also 42 of the bank’s subsidiaries[74]. The Deputy Secretary also emphasized that this type of sanction also includes restrictions on providing material assistance and investments to such sanctioned persons[75]. Individuals who provide such assistance run the risk of being added to the US sanctions list.

The dollar is an international currency; before the full-scale invasion, approximately 40% of global trade in goods was conducted in dollars[76]. All transactions made in dollars pass through the American system. This is why it is quite difficult for Russian banks to circumvent sanctions, even with the help of countries “friendly” to Russia. For example, on February 19, 2024, Ukrainska Pravda published information that banks in the United Arab Emirates have restricted settlements with Russia and begun closing accounts of legal entities and individuals[77]. The newspaper “Delovaya Gazeta” noted that “currently, UAE banks do not accept money from Russia and do not conduct payments in the opposite direction”[78]. The First Deputy Head of the Bank of Russia’s Financial Markets Service, V.Chistyukhin, has already emphasized this year that if the blocking of transactions continues, it will lead to the death of the Russian economy[79]. According to China, at the beginning of spring, 80% of transactions with Russia were suspended[80].

As mentioned above, the Russian economy depends on the export of gas, oil, and oil products. If the blocking of transactions continues, Russia will not be able to receive profits from foreign economic activities. In 2024, banks are feeling the impact of sanctions. For instance, Alfa Bank’s profit decreased more than threefold, to 8.5 billion rubles (almost $95 million), VTB and Sovcombank reduced their profits by 2.8 times, to 35.2 billion (about $4 billion) and 11.4 billion rubles ($1.2 billion) respectively[81]. The financial director of VTB Bank stated at the end of June 2024 that the imposed sanctions have complicated foreign trade operations conducted by Russian banks[82].

Therefore, the US and EU do not aim to completely undermine the Russian economy. The imposed economic sanctions are aimed at weakening Russia’s ability to continue military operations, support the military-industrial complex, update its technological park, and develop energy-intensive technologies.

Forecasts and Conclusions

The energy sector is crucial for Russia, as it is the primary source of funding for the war in Ukraine. The share of revenue from oil and gas accounted for about 50% of the federal budget in the second quarter of 2022[83].

The level of income from the energy sector has been gradually decreasing since the full-scale invasion. In the first half of 2022, Gazprom’s net profit could cover all of Russia’s national defense expenses[84]. However, by 2024, the company’s losses were estimated at $7 billion for the first time in 20 years. Given the points described above, the trend of decreasing cash inflows to Russia from the energy sector should not change in 2024 and 2025.

Firstly, Russia has lost the EU natural gas market. The Asian and African markets are less profitable for Russian companies, as the gas price is lower than what European countries used to pay. Moreover, China, one of the most attractive gas buyers for Russia, is not rushing to conclude additional agreements and increase the amount of imported Russian gas. This means that in 2024 and 2025, if the dynamics of sanctions do not change, Russia will not only be unable to regain its pre-war income from gas sales, but this income will decrease each year.

Secondly, Russia has lost the European oil market. As with the gas situation, the income received from Asian clients is inferior to the income that Russian companies received before the full-scale invasion. Reorienting to the Asian and African markets has only helped Russia maintain its crude oil production levels, but not maintain its income level.

At the same time, the price cap on oil imposed by the G7, EU, and other countries is not effective due to the countries’ unpreparedness to ensure Russia’s compliance with the oil price cap rules. No proper procedure for monitoring transactions and other procedures that would reduce the level of circumvention by Russian oil companies has been created. Furthermore, there are frequent cases where G7 and EU countries themselves help Russia not comply with the restrictions, particularly through insuring tankers and submitting documents with false data to the relevant authorities.

Russian financial institutions are also beginning to feel the impact of economic sanctions. Disconnection from SWIFT has complicated transactions between banks. Moreover, transactions are blocked not only by Western countries but also by states “friendly” to Russia (China, Turkey, UAE). The latter do this out of fear of secondary US sanctions being applied to them, which would effectively mean blocking access to the dollar and American financial institutions.

Since SWIFT is only a system that quickly and reliably transmits messages between banks, disconnecting Russian banks does not automatically mean that banks will lose the ability to conduct international transactions. As a result, disconnection from SWIFT should be considered in conjunction with direct sanctions on Russian financial institutions.

Russian Federation’s Position on Sanctions

In 2014, Putin emphasized that “no sanctions are effective in the modern world”, and that sanctions generally cause harm but are not critical to the Russian economy[85]. By 2023, Putin noted that “illegitimate restrictions imposed on the Russian economy can indeed negatively affect it in the medium term”[86]. Comparing these two statements by the Russian President gives grounds to say that the impact of sanctions on the Russian economy is becoming increasingly noticeable. Additionally, the head of the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, E.Nabiullina, stated that international payments have become a problem for Russia, specifically the inability of sanctioned Russian banks to make such payments[87]. She noted that this is a real problem that they will try to solve.

Despite these statements, a number of high-level Russian officials still claim that Russia is successfully coping with sanctions. The Prime Minister of the Russian Federation, M.Mishustin, stated that Russia plays a key role in forming centers of a “multipolar world”, successfully coping with sanctions[88]. Foreign Minister of Russia S.Lavrov, at a meeting with Moscow University students, stated that there are attempts to isolate Russia, but “these attempts are doomed to fail”[89]. In his opinion, the West has realized that sanctions not only do not work but also harm the initiators of restrictive measures themselves[90].

After the adoption of the 14th package of EU sanctions in June 2024, the Press Secretary of the President of the Russian Federation, D.Peskov, agreed that Western countries are imposing unprecedented sanctions. At the same time, he stated that the country [Russian Federation] will “try to minimize the consequences of such decisions”[91].

Conclusions and Recommendations for Government Authorities

One of the main ways to enhance the effectiveness of sanctions against Russia is to continue dialogue between states, non-governmental organizations, and public representatives. China, Iran, UAE, India, and similar countries (based on their attitude towards Russia) will continue to serve as hubs for circumventing sanctions against Russia. Dialogue with non-governmental organizations, public representatives, and officials of these countries may change behavior, but this scenario is unlikely in the short term.

Moreover, dialogue and strengthened cooperation directly between EU countries, G7, and Ukraine are necessary. G7 countries, the EU, and the US should unify their systems for monitoring compliance with sanctions against Russia. If the G7 and EU have set price caps on oil, these countries should simultaneously develop publicly available rules for detecting violations and subsequent actions, organizing an effective system for enforcing sanction prohibitions and restrictions.

[1] Koval, Dmytro, Bohdan Bernatskyi. “Sanctions Handbook: Lessons for Ukraine from the Practice of Foreign Sanctions Legislation and International Law”. zmina.ua, 2023. https://zmina.ua/publication/sankczijnyj-dovidnyk-uroky-dlya-ukrayiny-z-praktyky-inozemnogo-sankczijnogo-zakonodavstva-ta-mizhnarodnogo-prava.

[2] United Nations, “United Nations Charter (Full Text) | United Nations”, n.d., https://www.un.org/en/about-us/un-charter/full-text.

[3] “Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union”. 2012. Official Journal of the European Union C 326/49 (October). EUR-Lex – 12012E/TXT – EN – EUR-Lex (europa.eu).

[4] Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Jeffrey J Schott, Kimberly Ann Elliott, and Barbara Oegg. Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute For International Economics, 2009.

[5] Cory Welt, Kristin Archick, Rebecca M. Nelson, and Dianne E. Rennack. “U.S. Sanctions on Russia before 2022”. Congressional Research Service (CRS), January 18, 2018. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45415/13Cory%20Welt. P. 7.

[6] Julian Walterskirchen, Gerhard Mangott, and Clara Wend, Sanction Dynamics in the Cases of North Korea, Iran, and Russia, SpringerBriefs in International Relations, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17397-4.

[7] Cory Welt, Kristin Archick, Rebecca M. Nelson, and Dianne E. Rennack. “U.S. Sanctions on Russia before 2022”. Congressional Research Service (CRS), January 18, 2018. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45415/13Cory%20Welt.

[8] Cory Welt, Kristin Archick, Rebecca M. Nelson, and Dianne E. Rennack. “U.S. Sanctions on Russia before 2022”. Congressional Research Service (CRS), January 18, 2018. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45415/13Cory%20Welt. Pp. 39-40.

[9] Anton Moiseienko, “Are EU misappropriation sanctions dead?”, Völkerrechtsblog, 8 August 2019, https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/are-eu-misappropriation-sanctions-dead/

[10] “Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Task Force Ministerial Joint Statement”, March 17, 2022. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/russian-elites-proxies-and-oligarchs-task-force-ministerial-joint-statement

[11] U.S. Department of the Treasury. “Joint Statement from the REPO Task Force”, July 28, 2023. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy1329.

[12] “EU Appoints David O’Sullivan as International Special Envoy for the Implementation of EU Sanctions – European Commission”, December 13, 2022. https://ireland.representation.ec.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/eu-appoints-david-osullivan-international-special-envoy-implementation-eu-sanctions-2022-12-13_en.

[13] KSE Sanctions. “Yermak-McFaul Group – KSE Sanctions”, n.d. https://sanctions.kse.ua/en/yermak-mcfaul-group/.

[14] “G7 Statement on Support for Ukraine”, June 27, 2022. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2022/06/27/g7-statement-on-support-for-ukraine/; “G7 Leaders’ Statement on Ukraine”, May 19, 2023. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/05/19/g7-leaders-statement-on-ukraine/; “G7 Leaders’ Statement”, February 24, 2024. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2024/02/24/g7-leaders-statement-24-february-2024/.

[15] Daphne Psaledakis. “New Sanctions Imposed on Russia so Far as G7 Leaders Meet”. Reuters, May 19, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/world/new-sanctions-imposed-russia-so-far-g7-leaders-meet-2023-05-19/.

[16] The official website of the Council of the EU and the European Council. “Timeline – EU Sanctions against Russia”. n.d. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions-against-russia/timeline-sanctions-against-russia/?.

[17] Bohdan Bernatskyi. “What are the economic sanctions against Russia worth”. Economichna Pravda, November 16, 2021. https://www.epravda.com.ua/columns/2021/11/16/679813/.

[18] U.S. Department of State. “About Us – Office of the Chief Economist”, n.d. https://www.state.gov/about-us-office-of-the-chief-economist/.

[19] Daniel P. Ahn, and Rodney Ludema. “Measuring Smartness: Understanding the Economic Impact of Targeted Sanctions”. The Office of the Chief Economist (OCE), December 2016.

[20] Gerard DiPippo, and Andrea Leonard Palazzi. “Bearing the Brunt: The Impact of the Sanctions on Russia’s Economy and Lessons for the Use of Sanctions on China”. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), February 23, 2023.

[21] Valentin von Stosch. “Targeting the Assets of the Russian Central Bank”. Völkerrechtsblog, April 22, 2024. https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/targeting-the-assets-of-the-russian-central-bank/.

[22] Maria Demertzis, Benjamin Hilgenstock, Ben McWilliams, Elina Ribakova, and Simone Tagliapietra. “How Have Sanctions Impacted Russia?” Bruegel, October 26, 2022. https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/how-have-sanctions-impacted-russia.

[23] The official website of the Council of the EU and the European Council. “EU Sanctions against Russia Explained”, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions-against-russia/sanctions-against-russia-explained/.

[24] The official website of the Council of the EU and the European Council. “EU Sanctions against Russia Explained”, n.d. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/sanctions-against-russia/sanctions-against-russia-explained/.

[25] The official website of the European Commission. “Ukraine: EU and G7 Partners Agree Price Cap on Russian Petroleum Products”, February 4, 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_23_602.

[26] Gerard DiPippo, and Andrea Leonard Palazzi. “Bearing the Brunt: The Impact of the Sanctions on Russia’s Economy and Lessons for the Use of Sanctions on China”. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), February 23, 2023.

[27] Gerard DiPippo, and Andrea Leonard Palazzi. “Bearing the Brunt: The Impact of the Sanctions on Russia’s Economy and Lessons for the Use of Sanctions on China”. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), February 23, 2023.

[28] Vladimir Milov. “OIL, GAS, and WAR: The Effect of Sanctions on the Russian Energy Industry”. Atlantic Council, May 2024.

[29] Vladimir Soldatkin. “Gazprom Loss Shows Struggle to Fill EU Gas Sales Gap with China”. Reuters, May 13, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/gazprom-loss-shows-struggle-fill-eu-gas-sales-gap-with-china-2024-05-13/#:~:text=Russia%20supplied%20a%20total%20of,to%2028.3%20bcm%20last%20year.

[30] Arthur Sullivan. “War in Ukraine: Why Is the EU Still Buying Russian Gas?” DW, April 29, 2024. https://www.dw.com/en/war-in-ukraine-why-is-the-eu-still-buying-russian-gas/a-68925869#:~:text=According%20to%20EU%20data%2C%20the,to%20about%208%25%20in%202023.

[31] Vladimir Soldatkin. “Gazprom Loss Shows Struggle to Fill EU Gas Sales Gap with China”. Reuters, May 13, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/gazprom-loss-shows-struggle-fill-eu-gas-sales-gap-with-china-2024-05-13/#:~:text=Russia%20supplied%20a%20total%20of,to%2028.3%20bcm%20last%20year.

[32] Vladimir Soldatkin. “Gazprom Loss Shows Struggle to Fill EU Gas Sales Gap with China”. Reuters, May 13, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/gazprom-loss-shows-struggle-fill-eu-gas-sales-gap-with-china-2024-05-13/#:~:text=Russia%20supplied%20a%20total%20of,to%2028.3%20bcm%20last%20year.

[33] The Moscow Times. “As Power of Siberia 2 Pipeline Stagnates, so Do Russia’s Hopes for Pivoting Gas Exports Eastward”. June 21, 2024. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2024/06/20/as-power-of-siberia-2-pipeline-stagnates-so-do-russias-hopes-for-pivoting-gas-exports-eastward-a85468.

[34] AFP. “Russia to Finalize Route for Gas Pipeline to China”. The Moscow Times, September 6, 2023. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2023/09/06/russia-to-finalize-route-for-gas-pipeline-to-china-a82379.

[35] Reuters. “Explainer: Does China Need More Russian Gas via the Power-of-Siberia 2 Pipeline?” March 22, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/does-china-need-more-russian-gas-via-power-of-siberia-2-pipeline-2023-03-22/.

[36] Reuters. “Explainer: Does China Need More Russian Gas via the Power-of-Siberia 2 Pipeline?” March 22, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/does-china-need-more-russian-gas-via-power-of-siberia-2-pipeline-2023-03-22/.

[37] Bloomberg. “Russia Forecasts Lower Price for Its Gas to China versus Europe”. April 23, 2024. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-04-23/russia-forecasts-lower-price-for-its-gas-to-china-versus-europe.

[38] Bloomberg. “Russia Forecasts Lower Price for Its Gas to China versus Europe”. April 23, 2024. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-04-23/russia-forecasts-lower-price-for-its-gas-to-china-versus-europe.

[39] Interfax.ru. “The Income Tax Rate for LNG Producers May Rise to 32%”. September 23, 2022. https://www.interfax.ru/business/864698.

[40] Interfax.ru. “Yamal LNG Sent More than 70% of Gas to Europe in 2022”. July 12, 2023. https://www.interfax.ru/business/911284.

[41] Kate Abnett. “LNG Imports from Russia Rise, despite Cuts in Pipeline Gas”. Reuters , August 30, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/lng-imports-russia-rise-despite-cuts-pipeline-gas-2023-08-30/.

[42] Filip Rudnik. “The EU’s New Sanctions against Russia: Tighter Restrictions, a Ban on Re-Exporting LNG”. Centre for Eastern Studies (OSW), June 25, 2024. https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/analyses/2024-06-25/eus-new-sanctions-against-russia-tighter-restrictions-a-ban-re.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Elena Abramovich. “The First Gas Sanctions – the European Commission Told the Details of the 14th Package of Restrictions against Russia”. Radio Svoboda, June 24, 2024. https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/news-sanktsii-es-rosia/33006918.html.

[45] Gavin Maguire. “Oil Demand in Asia, Africa Boosted by Cheap Russian Crude”. Reuters, January 24, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/oil-demand-asia-africa-boosted-by-cheap-russian-crude-2024-01-24/

[46] Victoria Kim, and Clifford Krauss. “Asia Is Buying Discounted Russian Oil, Making up for Europe’s Cutbacks”. The New York Times, June 21, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/21/world/asia/asia-is-buying-discounted-russian-oil-making-up-for-europes-cutbacks.html

[47] Vladimir Milov. “OIL, GAS, and WAR: The Effect of Sanctions on the Russian Energy Industry”. Atlantic Council, May 2024.

[48] Gavin Maguire. “Oil Demand in Asia, Africa Boosted by Cheap Russian Crude”. Reuters, January 24, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/oil-demand-asia-africa-boosted-by-cheap-russian-crude-2024-01-24/.

[49] Gavin Maguire. “Oil Demand in Asia, Africa Boosted by Cheap Russian Crude”. Reuters, January 24, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/oil-demand-asia-africa-boosted-by-cheap-russian-crude-2024-01-24/.

[50] Borys Dodonov, Benjamin Hilgenstock, Anatoliy Kravtsev, Yuliia Pavytska, and Nataliia Shapoval. “Oil Revenues Decline despite Active Shadow Fleet and Higher Oil Prices”. KSE Institute, June 3, 2024. https://sanctions.kse.ua/en/oil-revenues-decline-despite-active-shadow-fleet-and-higher-oil-prices/.

[51] Vladimir Milov. “OIL, GAS, and WAR: The Effect of Sanctions on the Russian Energy Industry”. Atlantic Council, May 2024. P. 10.

[52] Bloomberg. “Russia Oil Resilience May Fade on Lack of Technology, Yakov Says”. March 2, 2023. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-03-02/russia-oil-resilience-may-fade-on-lack-of-technology-yakov-says.

[53] Ben Cahill. “Progress Report on EU Embargo and Russian Oil Price Cap”. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), January 10, 2023.

[54] Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions. “Working Group Paper #18: ‘Energy Sanctions: Four Key Steps to Constrain Russia in 2024 and Beyond.’” KSE Institute, February 7, 2024. P. 8.

[55] Ben Hilgenstock, Elina Ribakova, and Nataliia Shapoval. “Bold Measures Are Needed as Russia’s Oil Is Slipping beyond G7 Reach”. KSE Institute, November 20, 2023. P. 2.

[56] Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions. “Working Group Paper #18: ‘Energy Sanctions: Four Key Steps to Constrain Russia in 2024 and Beyond.’” KSE Institute, February 7, 2024.

[57] Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA). “Tracking the Impacts of G7 & EU’s Sanctions on Russian Oil “. n.d. https://energyandcleanair.org/russia-sanction-tracker/.

[58] Borys Dodonov, Benjamin Hilgenstock, Anatoliy Kravtsev, Yuliia Pavytska, and Nataliia Shapoval. “Oil Revenues Decline despite Active Shadow Fleet and Higher Oil Prices”. KSE Institute, June 3, 2024. https://sanctions.kse.ua/en/oil-revenues-decline-despite-active-shadow-fleet-and-higher-oil-prices/.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions. “Working Group Paper #18: ‘Energy Sanctions: Four Key Steps to Constrain Russia in 2024 and Beyond.’” KSE Institute, February 7, 2024. P. 9.

[62] Vladimir Milov. “OIL, GAS, and WAR: The Effect of Sanctions on the Russian Energy Industry”. Atlantic Council, May 2024. P. 12.

[63] Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions. “Working Group Paper #18: ‘Energy Sanctions: Four Key Steps to Constrain Russia in 2024 and Beyond.’” KSE Institute, February 7, 2024. P. 10.

[64] Borys Dodonov, Benjamin Hilgenstock, Anatoliy Kravtsev, Yuliia Pavytska, and Nataliia Shapoval. “Oil Revenues Decline despite Active Shadow Fleet and Higher Oil Prices”. KSE Institute, June 3, 2024. https://sanctions.kse.ua/en/oil-revenues-decline-despite-active-shadow-fleet-and-higher-oil-prices/.

[65] Valentin von Stosch. “Targeting the Assets of the Russian Central Bank”. Völkerrechtsblog, April 22, 2024. https://voelkerrechtsblog.org/targeting-the-assets-of-the-russian-central-bank/.

[66] Kirstin Ridley, and Karin Strohecker. “Explainer: Disconnecting Russia’s Banks: Sberbank Faces SWIFT Removal”. Reuters , May 5, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/disconnecting-russias-banks-sberbank-faces-swift-removal-2022-05-05/.

[67] Ananya Kumar , and Josh Lipsky. “The Dollar Has Some Would-Be Rivals. Meet the Challengers”. Atlantic Council, September 22, 2022. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-dollar-has-some-would-be-rivals-meet-the-challengers/

[68] Ananya Kumar , and Josh Lipsky. “The Dollar Has Some Would-Be Rivals. Meet the Challengers”. Atlantic Council, September 22, 2022. https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-dollar-has-some-would-be-rivals-meet-the-challengers/

[69] Abely, Christine. 2023. The Russia Sanctions. Cambridge University Press. P. 29.

[70] European Pravda. “EU Imposes Sanctions against Russian Analogue of SWIFT”. June 24, 2024. https://www.eurointegration.com.ua/eng/news/2024/06/24/7188761/.

[71] The official website of the European Commission. “EU Adopts 14th Package of Sanctions against Russia for Its Continued Illegal War against Ukraine, Strengthening Enforcement and Anti-Circumvention Measures”, June 24, 2024. https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/news/eu-adopts-14th-package-sanctions-against-russia-its-continued-illegal-war-against-ukraine-2024-06-24_en

[72] U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY. “U.S. Treasury Escalates Sanctions on Russia for Its Atrocities in Ukraine”. April 6, 2022. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0705#:~:text=SBERBANK%20AND%2042%20SBERBANK%20SUBSIDIARIES,all%20bank%20assets%20in%20Russia.

[73] Washington Post Live. “Wally Adeyemo Explains ‘Full-Blocking Sanctions.'” YouTube, March 4, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=QWFiqKsEIxM.

[74] U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY. “U.S. Treasury Escalates Sanctions on Russia for Its Atrocities in Ukraine”. April 6, 2022. https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0705#:~:text=SBERBANK%20AND%2042%20SBERBANK%20SUBSIDIARIES,all%20bank%20assets%20in%20Russia.

[75] Washington Post Live. “Wally Adeyemo Explains ‘Full-Blocking Sanctions.'” YouTube, March 4, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=QWFiqKsEIxM.

[76] Abely, Christine. 2023. The Russia Sanctions. Cambridge University Press. P. 33.

[77] Ukrainska Pravda. “UAE Banks Limit Business with Russia and Begin Closing Accounts of Russian Clients”. February 19, 2024. https://www.pravda.com.ua/eng/news/2024/02/19/7442486/index.amp

[78] Oleksii Pavlysh. “UAE Banks Have Limited Settlements with the Russian Federation and Began to Close the Accounts of Russian Clients – Media”. Epravda, February 19, 2024. https://www.epravda.com.ua/news/2024/02/19/710084/index.amp

[79] The Moscow Times. “The Central Bank Announced the Threat of Death of the Russian Economy due to Sanctions”. June 26, 2024. https://www.moscowtimes.ru/2024/06/26/v-tsb-zayavili-ob-ugroze-smerti-rossiiskoi-ekonomiki-iz-za-sanktsii-a135115

[80] The Moscow Times. “The Central Bank Announced the Threat of Death of the Russian Economy due to Sanctions”. June 26, 2024. https://www.moscowtimes.ru/2024/06/26/v-tsb-zayavili-ob-ugroze-smerti-rossiiskoi-ekonomiki-iz-za-sanktsii-a135115

[81] Yuriy Tarasovskyi. “Profits of Large Russian Banks Collapsed due to Sanctions and ‘War Tax.'” Forbes, May 16, 2024. https://forbes.ua/news/pributki-velikikh-rosiyskikh-bankiv-obvalilisya-cherez-sanktsii-ta-podatok-na-viynu-16052024-21190

[82] Reuters. “Russia’s VTB Bank Says US Sanctions Have Complicated Cross-Border Transactions”. June 28, 2024. https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/russias-vtb-bank-says-us-sanctions-have-complicated-cross-border-transactions-2024-06-28/.

[83] Gerard DiPippo, and Andrea Leonard Palazzi. “Bearing the Brunt: The Impact of the Sanctions on Russia’s Economy and Lessons for the Use of Sanctions on China”. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), February 23, 2023.

[84] Gerard DiPippo, and Andrea Leonard Palazzi. “Bearing the Brunt: The Impact of the Sanctions on Russia’s Economy and Lessons for the Use of Sanctions on China”. Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), February 23, 2023. P. 11.

[85] Ukrainska Pravda. “Putin Says Western Sanctions Will Help Make Russia Independent”. April 24, 2014. https://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2014/04/24/7023488/

[86] Hanna Ziady. “Putin Admits Sanctions Could Hurt Russia’s Economy”. CNN, March 30, 2023. https://edition.cnn.com/2023/03/30/economy/putin-russia-sanctions/index.html

[87] Laura Keffer. “Nabiullina: Disconnection from SWIFT and Freezing of Assets Are the Most Painful Sanctions”. Kommersant, December 25, 2023. https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6425864

[88] Ria.ru. “Russia Is Successfully Coping with Sanctions, Mishustin Said”. July 9, 2024. https://ria.ru/20240709/sanktsii-1958495366.html

[89] Vesti.ru. “Anti-Russia” Failed, Western Sanctions Do Not Work”. September 1, 2022. https://www.vesti.ru/article/2919689

[90] Vesti.ru. “Anti-Russia” Failed, Western Sanctions Do Not Work”. September 1, 2022. https://www.vesti.ru/article/2919689

[91] Kommersant. “Peskov on the 14th Package of Sanctions: The EU Will Impose New Restrictions Even to Its Detriment”. April 22, 2024. https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6663465

© Centre for International Security

Author:

Bohdan Bernatskyi

The information and views set out in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect

the official opinion of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine.

Centre for International Security

Borodina Inzhenera Street, 5-А, Kyiv, 02092, Ukraine

Phone: +380999833140

E-mail: cntr.bezpeky@gmail.com