EAST ASIA – UKRAINE: TIME FOR REDEFINING RELATIONS

Group of authors:

Mykhailo Honchar, Serhii Vyshnivetskyi,

Oksana Bukovynska, Oksana Ishchuk

1. INTRODUCTION. NEW GEOPOLITICAL CONFIGURATIONS

The February wave of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, which has been continuing since 2014, is radically changing the geopolitical balance in the world, forcing politicians and ordinary citizens to reflect on the existing order of things. This aggression is not only a war against the Ukrainian people, but also against democracy and freedom in general. Over the past few decades, countries with strong autocratic systems have consolidated their efforts to expand their geopolitical influence in the world. This applies to China, Russia, Iran, North Korea, Belarus, Venezuela. The current regimes in Türkiye, Brazil, a number of countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America gravitate towards this informal alliance of autocracies.

The world is at the stage of tectonic change of the geo-economic and geopolitical order established after the Second World War, where Western civilization dominated in one way or another. The world of the XXI century is becoming increasingly less the world of the West, the world of Europe and more the world of the East, the world of Asia. However, the Asian world is dominated by autocratic regimes. In fact, starting in the west of the continent with Türkiye and ending in its Far East with China, Asia is represented by a belt of countries with authoritarian regimes at the head. The only exception is Northeast Asia.

Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have become the Asian stronghold of Western civilization. Moreover, by combining the Western model of democracy and freedom of enterprise with national traditions and business practices, they have turned into the drivers of technological development on a global scale. In the late XX—early XXI century, these three countries outperformed the transatlantic world, demonstrating a clear result of the synergy of Eastern and Western models.

The realities of the XXI century are the global solidarity of autocracies with all the divergence of their interests. China, Iran, Türkiye, Russia de facto form a Eurasian alliance against the democracies of Europe and North America, seizing footholds, including in Europe. China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization is a clear evidence of such solidarity. A stark example of the capture of positions in the Western world by the forces of global autocracy is formally democratic, in fact neo-authoritarian Hungary. The world has become multi-polar with such swing states as Türkiye, India, Brazil, South Africa, Mexico, Indonesia, which, remaining in the middle between democracy and authoritarianism, tend to change the pole according to their situational interests.

Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, which has been going on since 2014 and escalated by the Kremlin in February 2022, forces Ukraine to reconsider its strategies for survival and further recovery and development. Kyiv’s exclusively pro-Western orientation in the traditional understanding of the West as a transatlantic alliance of Europe, the United Kingdom and North America does not give a comprehensive result either in the issue of security or in the issue of further restoration of the country and its development as an integral part of Western alliances—NATO and the EU.

Russian aggression against Ukraine has clearly demonstrated the political bankruptcy of the Franco-German tandem as the locomotive of Europe. It proved to be unable to stop the aggressor, moreover, the double-dealing activities of Berlin and Paris in recent years aimed at preserving the status quo of trade and economic relations with Russia became an additional incentive for the escalation of its aggressive actions against Ukraine, Europe and the West as a whole.

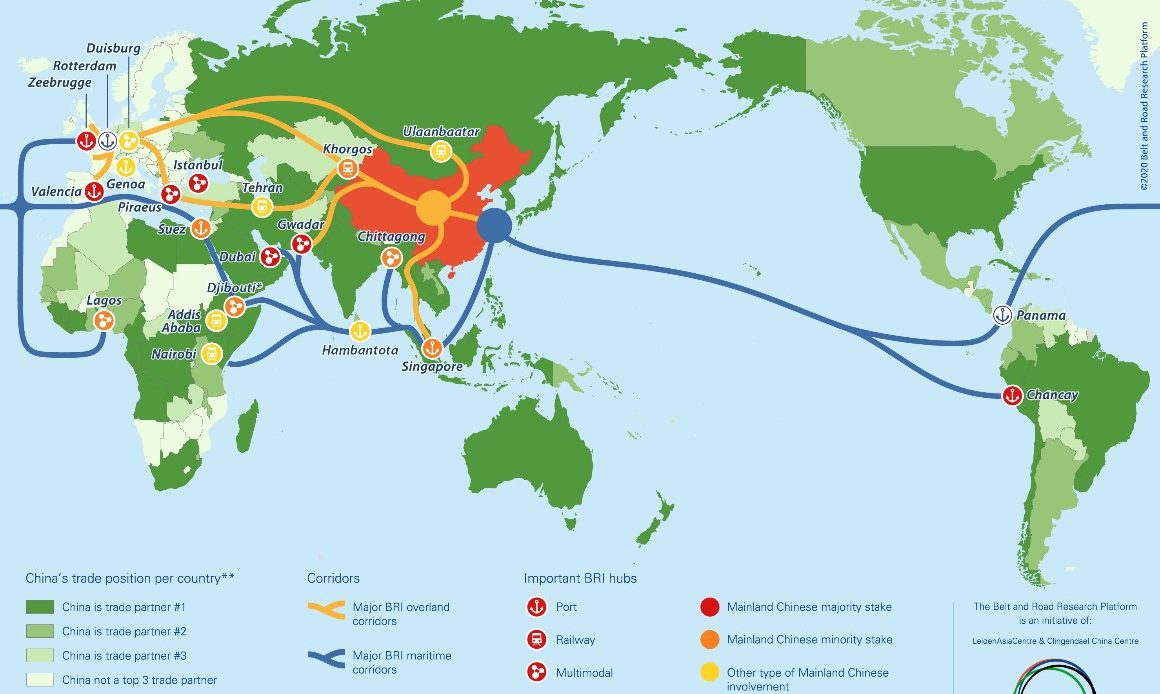

The model of focusing on China as a global engine of development is also ineffective. China cares only about its own growth, having created its own globalization project called “One Belt, One Road,” unique in scale and manipulativeness. This project of Chinese expansionism, in fact, does not serve the synergy of development, but is rather a mechanism of velvet colonization through corrupt practices in third countries, which have been perfected by Chinese corporate entities over a long period of foreign economic activity.

In view of the above, it is vital for Ukraine to use the potential of relations with the countries of East Asia, which are modern technological locomotives, have a powerful investment potential and stand as the eastern outpost of Western civilization. Moreover, the West itself is also heading to the East. The Quadripartite Security Dialogue (the Quad) and the trilateral format AUKUS are proof of this. Ukraine has a long history of relations with Japan and South Korea. It is time to look towards Taiwan as well, while maintaining a formal “One China” position.

2. UKRAINE—EAST ASIA: PRIORITIES

2.1. Ukrainian focus of Japan’s policy

Northeast Asia—Japan, South Korea, Taiwan—is a conditional bastion of Western-oriented Eastern democracies, relations with which are underestimated by Ukraine. It is high time to reassess these approaches.

The reaction to the Russian aggression against Ukraine was different—from outright condemnation by Japan and Taiwan to cautious opposition by South Korea, but unequivocally negative towards the aggressor. Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore immediately joined the Western countries in supporting Ukraine.

On September 22, during a meeting with his Ukrainian counterpart Denys Shmyhal in New York on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly, Prime Minister of Japan Fumio Kishida emphasized his country’s determination to defend the international order based on the rule of law. Prime Minister Kishida noted that Japan’s position in support of Ukraine remains unchanged and Japan stands with the people of Ukraine[1]. The Prime Minister of Japan has repeatedly expressed his commitment to Ukraine in repulsing the aggression of the Russian Federation in his phone conversations with the President of Ukraine.

Japan has become the defender of Ukraine in Southeast Asia as part of the Indo-Pacific region. In May 2022, Fumio Kishida visited Indonesia, Vietnam and Thailand. In turn, Japanese Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi paid visits to Central Asia—Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Mongolia. These visits were aimed at promoting a common Asian stance in support of the G7 position on Russian aggression against Ukraine ahead of the G20 summit in Bali in November 2022. Democratic governments of Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, quasi-democratic Singapore have taken a clear pro-Ukrainian position.

In this context, the Decree of the President of Ukraine No. 692/2022 of October 7, 2022, which reaffirms respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Japan, including its Northern Territories, which continue to be under the occupation of the Russian Federation, is a strategically correct decision.

Kyiv’s Sino-centric policy, aimed exclusively at Beijing, is becoming an anachronism. Especially when it comes to the fact that the main players—the United States and the EU—take an increasingly clear and unambiguous position of opposing Chinese expansionism and attempts to establish hegemony in certain regions of the world. Although we primarily refer to China’s dominance in Africa, the Chinese challenge to the West is not limited to it.

2.2. EU and the US: Identification of the Chinese threat

Chinese penetration into Europe, as well as crypto-war—a war without the use of weapons, but involving cyber-attacks, hacking, propaganda, corruption, technological espionage—against Europe from within Europe, following a pattern largely similar to the Russian one, are the realities of the modern EU. Therefore, the European Commission for the first time has explicitly not only acknowledged the existence of the Chinese challenge, but also its readiness to counter it.

On October 10, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Defense Josep Borrell made a speech in which he recognized the fallacy of certain approaches of the European Union: “Our prosperity has been based on cheap energy coming from Russia… And the access to the big China market, for exports and imports, for technological transfers, for investments, for having cheap goods… Chinese workers with their low salaries have done much better and much more to contain inflation than all the Central Banks together…the fact that Russia and China are no longer the ones that they were for our economic development will require a strong restructuring of our economy…”.

A month earlier, the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen in her annual message to the European Parliament on September 14 quite clearly stated: “…we should not lose sight of the way foreign autocrats are targeting our own countries. Foreign entities are funding institutes that undermine our values. Their disinformation is spreading from the internet to the halls of our universities. Earlier this year, a university in Amsterdam shut down an allegedly independent research centre, which was actually funded by Chinese entities. This centre was publishing so-called research on human rights, dismissing the evidence of forced labour camps for Uyghurs as ‘rumours’…”.

“…we introduced legislation to screen foreign direct investment in our companies for security concerns. If we do that for our economy, shouldn’t we do the same for our values? We need to better shield ourselves from malign interference. This is why we will present a Defence of Democracy package. It will bring covert foreign influence and shady funding to light.”[2]

In this context, the political playing up to China, which Ukraine engaged in on October 6 this year by not supporting the UN Human Rights Council resolution to discuss the alleged genocide of Uyghurs in China, undermines Ukraine’s credibility.

The US is even more unambiguous in positioning the Chinese threat as the number one priority for national defense. The secret 2022 National Defense Strategy document identifies four defense priorities, two of which relate to China, defined as “the most consequential strategic competitor and the pacing challenge.”[3] Russia is recognized as an “acute threat” in Europe. One can argue with the adequacy of the perception of global realities by American analysts (the example of forecasts for Ukraine just shows their inadequacy and erroneous perception of realities, bordering on unprofessionalism), but this is the official vision on the banks of the Potomac.

This year, European countries take an active part in the American operation to ensure freedom of navigation in the South China Sea. The naval presence of the US 7th Fleet in the region is a well-known fact. Europe has not been a partner in the US Navy’s operations in the Pacific until recently. This year, the United Kingdom and France have sent ship strike groups to the South China Sea, Germany has added its frigate to the operation, as well as the Netherlands, whose frigate has been a part of the United Kingdom aircraft carrier group.

Ukraine proposes to the US and the EU to initiate a similar operation to ensure freedom of navigation in the Black and Azov Seas, where Russia has imposed a naval blockade of Ukrainian ports. In accordance with the US-Ukraine Charter on Strategic Partnership, signed on November 10, 2021, both countries are identified as key partners in the Black Sea to ensure freedom of navigation and effectively counter external threats and challenges in all domains[4]. Kyiv wants the European Parliament, the US Congress, the UK Parliament to adopt relevant resolutions in support of the restoration of freedom of navigation in the Black Sea.

If Ukraine wants its partners to cooperate in the issue of restoring freedom of navigation in the Azov-Black Sea basin, through which more than 70% of domestic exports go, it is necessary not only to take into account their position on China, but also to participate in the policy of deterring its expansionism both on the European continent and within the country in particular.

2.3. Ukraine’s policy as reflected in official documents

If we examine the strategic direction of the state’s geopolitical orientation, the National Security Strategy, approved by the President of Ukraine in 2020, clearly sets priorities:

34. Acquisition of full membership of Ukraine in the European Union and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization is the strategic course of the state[5].

35. Comprehensive cooperation with the United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, the Federal Republic of Germany, the French Republic has a strategic priority for Ukraine and is aimed at strengthening guarantees of independence and sovereignty, promoting democratic progress and development of Ukraine[6].

The basic provisions of the National Security Strategy are also reflected in another document—the Strategy of Foreign Policy of Ukraine, approved by the NSDC and signed by the President of Ukraine in 2021:

2. The basis of Ukraine’s foreign policy is the strategic course of the state for Ukraine’s full membership in the European Union (EU) and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), enshrined in the Constitution of Ukraine[7].

4. Foreign policy efforts will be aimed at developing strategic relations with key partners in the international arena, primarily with the EU, NATO and their member states[8].

The National Security Strategy does not mention China, except that it is included in the general formula for the development of mutually beneficial economic cooperation with the leading Asian countries[9]. But in the Strategy of Foreign Policy of Ukraine, China is given more attention and some points of the document directly contradict the National Security Strategy, which is the core for all other doctrinal documents of the state, as indicated in the final provisions[10].

In particular, it says that “in accordance with the concluded international treaties Ukraine will develop strategic partnership with the People’s Republic of China.”[11] Obviously, such fixation is a dubious attempt to legalize the status of China as a strategic partner bypassing the basic document of higher order, which is the National Security Strategy.

The following paragraph of the Strategy of Foreign Policy of Ukraine is indicative:

125. The development of relations with the People’s Republic of China will be carried out on the basis of the principles of international law on respect for state sovereignty and territorial integrity of states through the implementation of basic interstate documents, in particular the Joint Declaration on Establishment and Development of Strategic Partnership Relations between Ukraine and the People’s Republic of China, signed on June 20, 2011. Foreign policy efforts will be aimed at intensification of political dialogue, further liberalization of trade and visa regime, practical filling of bilateral relations by launching and implementing joint projects in the spheres of infrastructure, energy, transport, industrial production[12].

It is noteworthy that the mentioned Joint Declaration on the Establishment and Development of Strategic Partnership Relations between Ukraine and the People’s Republic of China cannot be found in official databases. Its content remains unknown, as well as the status of the document. Obviously, its absence in the public domain means, at least, that the signed declaration has not passed the relevant internal procedures to enter into force. The reference to an invalid document with uncertain status in an official state document is particularly questionable.

Another point that raises concerns is related to the record of Ukrainian interest in the Chinese expansionism project “One Belt, One Road”:

144. Ukraine is interested in participating in global Asian projects, in particular within the framework of the “One Belt, One Road” initiative of the People’s Republic of China, to the extent that does not hinder the implementation of Ukraine’s European and Euro-Atlantic integration[13].

At the same time, the “OBOR” maps record only trade routes bypassing Ukraine either from the north (through Russia and Belarus) or from the south (through Central Asia—Iran—Türkiye).

In other words, the Chinese project does not really envisage Ukraine as a “strategic partner”, preferring the Russia-Belarus corridor to access the EU market, its logistics hubs and ports, although the most convenient route goes through Kazakhstan, Russia and Ukraine. It is evident that Russian aggression has made it impossible to implement this option since 2014, however, later on, the Chinese side did not make any efforts to deter Russia, guided by its own priority to create the most economically optimal logistics schemes. This once again suggests that the “OBOR” is a geopolitical project of Chinese expansionism, which considers the post-Soviet territory as a zone of Russia, which in turn is the sphere of influence of China—a kind of geopolitical nesting doll.

Nevertheless, the main conclusion that can be drawn is that the strategic partnership with China harms Ukraine’s Euro-Atlantic and European integration.

Other positions reflected in the Strategy of Foreign Policy of Ukraine are global partnership with Japan:

“126. A stable political ally in the Asian region is Japan, relations with which are defined as a global partnership.”

and even more vague and uncertain partnership with South Korea:

“146. The Republic of Korea is one of the leading trading partners of Ukraine in Asia… Ukraine is interested in intensifying political dialogue and enhancing trade and investment cooperation with the Republic of Korea.”

The imbalances of Ukraine’s foreign policy orientations in East Asia are obvious. Ukraine’s long-term geo-economic interests dictate the need for Kyiv to shift the focus of Ukrainian policy to cooperation with Japan and South Korea instead of the traditional orientation towards authoritarian China, which did not pass the wartime test.

A step in the direction of Tokyo was made by Ukraine’s recognition of Japan’s sovereignty over the Kuril Islands—Etorofu, Kunashiri, Shikotan and Habomai, which are the Northern territories of the country occupied by the Russian Federation[14]. In 2023, Japan will preside in the G7 and hold an summit of the leading group of Western countries, which is important for Ukraine, where the issue of post-war reconstruction of the country will be discussed[15].

Japan will also be a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council during 2023-2025. Ambassador of Japan to Ukraine Kuninori Matsuda, speaking on October 9, 2022 at the Kyiv-Mohyla Business School, emphasized to the Ukrainian audience that Ukraine should focus not only on cooperation in the Euro-Atlantic region, but also in the Indo-Pacific region, where Japan is located[16].

A natural complement to the East Asian direction of Ukrainian policy should be pragmatic economic relations with Taiwan. Without this component, the Sino-centric vector of Ukraine’s foreign policy looks artificially curtailed.

3. PECULIARITIES OF ECONOMIC RELATIONS WITH CHINA AND TAIWAN

3.1. Ukrainian-Chinese trade and investment

Ukraine’s exports to China have grown by 12.2% annually over the past 25 years[17]. In 2020, Ukraine exported goods to China worth $7.26 billion, including iron ore, corn and vegetable oil[18]. In 2021, exports amounted to $9.4 billion, while imports from China totaled $9.8 billion[19]. Thus, the trade balance has a small negative balance.

China imports several strategically important goods from Ukraine. These include agricultural products and iron ore. Over the past five years, China has deepened its dependence on Ukrainian corn imports. The Chinese food processing and trading company COFCO International has the third largest production and transportation capacities in Ukraine after Brazil and Argentina. In particular, it operates its own port terminal in Mykolaiv, four grain elevators along the Dnipro river, and runs a sunflower seed processing plant near Mariupol[20].

At the same time, over the past decades, cooperation between China and Ukraine in the military-technical field has enabled Beijing to gain some independence from Russian technology. Ukraine was the third largest supplier of weapons to China after Russia and France[21]. In recent years, Ukraine’s defense exports to China consisted of gas turbines for Chinese destroyers, aircraft turbofan engines, tank diesel engines, and several Il-78 transport aircraft[22].

China also imported neon from Ukraine. Before the war, Ukraine supplied 55% of neon to the world market[23]. It was produced by the Ingas in Mariupol and Cryoin in Odesa. They purified neon received from Russian steel mills. With the beginning of the war, they stopped their operations.

China has traditionally been interested in several areas of investment in Ukraine, which include agriculture, processing of agricultural products, port and railway infrastructure, renewable energy, and defense industry.

From 2016 to 2021, China increased the rate of investment in Ukraine’s economy fivefold to $260 million, according to a survey by the Centre for Economic Strategy[24]. In fact, real investment in Ukraine’s economy by the PRC is associated with only a few transactions, in particular, the acquisition by CNBM of solar power plants of the Active Solar group and the acquisition by COFCO of a number of assets engaged in the logistics of agricultural products[25].

In general, as for Beijing’s direct investments, their share is less than 1%[26]. At the same time, investments from EU countries account for 72%[27]. It should be noted, however, that many Chinese companies operating and investing in Ukraine are registered in other jurisdictions and use their regional centers in Europe or Central Asia to acquire shares or ready-made businesses. Beijing’s private presence and FDI levels are notably higher than those reflected in official statistics, due to special investment mechanisms. Chinese state-owned enterprises have lucrative contracts in Ukraine for civil infrastructure projects (roads, port terminals, railways, metro lines, power plants) and private industrial enterprises, the value of which since 2011 has exceeded $7 billion[28].

3.2. Growing risks of mono-orientation towards China

Foreign experts have repeatedly emphasized the risks of cooperation with China, referring to non-transparent mechanisms with a corruption component, hidden costs and certain political requirements to Ukraine. The fact is that China’s investments in young democracies have their own specifics in comparison to the way the West invests.

Studies have shown that investment (loan) agreements with China in most cases are based on non-public agreements between officials of both countries, may have concealed economic and political conditions. Experts assert that some of China’s investments go through Singapore, the Netherlands and various offshore companies. China often uses debt instruments, and loans are provided by state-owned banks. The largest investors are Chinese state-owned enterprises, and accordingly, everything happens only with the consent of the Chinese government. Chinese companies worked with Ukrainian state-owned enterprises in the fuel and energy sector, agriculture, and defense industry.

In addition, China is not ready to take responsibility for risks. A significant part of the agreements required the participation of the Ukrainian government and state guarantees. Experts also note that most Chinese investments create little added value.

The specific feature of the agreements with China is that this country often seeks to include in the contract a condition on the transfer of intellectual property, and if it fails to do so, it focuses on copying the necessary equipment, ensuring the transfer of important production to China, etc. This can be called a kind of intellectual raiding and industrial espionage. China also demands higher interest rates than Western donors, but instead does not insist on reforms, which is very appealing to the corrupt bureaucracy.

China has demonstrated rather un-partner-like behavior towards Ukraine. There was a notorious scandal regarding the attempt of Chinese private and state capital to gain full control over one of the leading Ukrainian defense industry enterprises called Motor Sich. These steps were timely blocked by the Antimonopoly Committee, the Security Service of Ukraine, the courts and the National Security and Defense Council. Another controversial case was the Ukrainian-Chinese agreement on joint serial production of An-225 Mriya[29]. This became public in 2016. Fortunately, this attempt was eventually stopped.

Equally well-known is the case of the Varyag aircraft carrier, which remained in Ukraine in an unfinished state (completed by 67%)[30] after the collapse of the USSR. In 1998, it was actually purchased by a Chinese company at the price of scrap metal—$20 million under the guise of a project to create an original floating entertainment center[31]. From 2005 to 2010 the ship was overhauled, completed and modernized. Within two years, China conducted its tests in the highest secrecy. On September 25, 2012, the first aircraft carrier entered the PLA Navy under the name Liaoning[32]. This was the first episode of Beijing’s large-scale deception of Kyiv.

It is also noteworthy that Russian troops, destroying industrial infrastructure by massive shelling, refrain from firing on objects owned or controlled by Chinese investors. According to some reports, this is the result of a high-level bilateral agreement that Chinese assets will not be damaged during the fighting, and the planned investments will be preserved. Probably, Beijing expects to get the assets of Motor Sich intact, and Russian troops are trying to capture Zaporizhzhia at any cost to demonstrate Moscow’s contractual capacity.

3.3 Central Europe, China and Taiwan: Evolution vector of relations

In April 2022, it was ten years since the establishment of the 17+1 format of cooperation between China and the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, which included Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary: Latvia, Lithuania, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Slovenia “plus” China. Despite Beijing’s tendency to celebrate such dates loudly, the anniversary passed unnoticed. China sent Special Representative Huo Yuzhen on a tour of the region in April 2022 to “further promote cooperation… and to dismiss misunderstandings, especially over China’s stance on the Ukraine crisis.”[33]

China’s refusal to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was probably the last straw for the 17+1 format, which was already in decline. Ukraine played an instrumental role in disengaging CEE from China, as many countries in the region are wary of Russia, and China is perceived as a close partner of Russia. The exceptions are Russia’s “Trojan horses” in Europe—Hungary and Serbia.

The 17+1 format gained particular momentum in 2013, with the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative. The CEE region has become a key in Xi Jinping’s plans to create a transcontinental infrastructure that would connect China with the markets of Western Europe.

In the meantime, CEE countries hoped for Chinese investment and trade. Over time, these hopes were dashed, and Chinese investment and trade continued to flow to richer Western European countries. Instead of infrastructure, they received forums, instead of factories—exchange programs, instead of exports—summer camps.

Brussels began to suspect that the purpose of the 17+1 mechanism was to sow discord within the European Union, although Beijing repeatedly denied such intentions. Of the seventeen countries in the format, twelve are EU members and the existence of a separate foreign policy towards China has raised questions in the European Commission.

In April 2021, Lithuania announced its withdrawal from the 17+1, and in the summer of the same year allowed the opening of the Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius. Since then, Beijing has imposed unofficial sanctions on Lithuania, including a list of goods banned for export. In February, the 17+1 format suffered a fatal blow with Russia’s attack on Ukraine.

China’s cooperation with Russia has always been a concern for CEE countries, which see Russia as a threat to their national security. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine proved to them that Moscow remains a serious, even existential threat. In this context, China’s reaction—not only refusing to condemn Russia for the attack, but also blaming NATO for the bloodshed—has deprived Beijing of any credibility as a reliable partner. After all, 15 of the 17 countries are NATO members, with the exception of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. They see China downplaying their security concerns and justifying Russia’s decision to attack a neighboring country.

China’s arrogant rhetoric towards Europe, the tendency to interpret every move of a partner country as orchestrated by Washington, is also not conducive to good relations. For example, during the tour of the CEE countries by the aforementioned Huo Yuzhen, the Huanqiu Shibao wrote: “Deeply influenced by the US, some CEE countries consider condemning Russia as ‘politically correct,’ and they see China’s stance on Ukraine very emotionally and such emotion has spilled over to bilateral cooperation. China’s pragmatic cooperation with CEEC has been affected by geopolitics and emotions fanned by the US.”[34]

This attitude of Beijing gains no support from the CEE countries. Even if China’s format with CEE countries survives, it will no longer be 17+1. It seems that Beijing realizes its failure in the CEE, although it does not admit it. The articles published on the eve of Xi Jinping’s visits to Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan in the leading media of these countries, indicate the focus of Chinese policy on Central Asia and its two leading countries, which fits into the strategic format of “China—Central Asia,” announced by Beijing. Obviously, Beijing has finally decided that the adjacent region of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan) is a higher priority than the distant pro-Western and, in China’s view, the most pro-American region of Central Europe (the Baltic States, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Romania and Ukraine).

3.4. Ukraine and Taiwan in the context of the “One China” policy

Within the framework of the “One China” policy, Ukraine mainly focused on cooperation with China and underestimated Taiwan. But the war demonstrated that such orientation is inadequate to the current state of affairs and trends.

Although bilateral cooperation began in 1992, it remained at the level of informal relations. There is still no representative office of Ukraine in Taiwan, as well as no representative office of Taiwan in Ukraine. It was an anomaly that consular issues were resolved through the Taipei Bureau in Moscow. Importantly, two days after the Russian armed invasion of Ukraine, on February 26, Taipei transferred the relevant powers to its representative office in Warsaw.

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the Taiwanese government actively worked to establish diplomatic relations with independent Ukraine. At the same time, the People’s Republic of China was also in the process of establishing diplomatic relations with Ukraine. It succeeded in its efforts and expressed sharp protests at every attempt by Taiwan to establish cooperation with Ukraine.

As a result, the proposal to establish official Ukrainian-Taiwanese relations was rejected. Through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ukraine assured that it “considers Taiwan an inseparable part of China.” Although Ukraine continued to maintain unofficial ties with Taiwan, it adhered to a policy of distancing from the latter at the official level.

In 2005, bilateral trade between Taiwan and Ukraine amounted to almost $300 million. Taiwan mainly exports to us information and telecommunications equipment, electronics parts, steel and automotive parts. Ukrainian imports include chemicals, oil, metals (aluminum, iron, steel, zinc) and agricultural products. Ukraine has all chances to deepen cooperation with Taiwan in the field of high technologies, development of 5G network.

In 2007, the Association for the Development of Foreign Trade of the Republic of China (Taiwan) established the Taiwan Trade Center in Kyiv, but the lack of official representations in both countries did not allow this cooperation to develop fully. Bilateral trade between Taiwan and Ukraine also began to noticeably drop.

In practice, Kyiv’s position continues to be based on the Joint Statement of the fugitive President Viktor Yanukovych and Chinese President Hu Jintao of September 2, 2010 on the comprehensive enhancement of the Chinese-Ukrainian relations of friendship and cooperation. It states: “The two sides believe that mutual support on issues related to state sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity is at the core of Chinese-Ukrainian relations”, “the Ukrainian side reaffirmed that it supports and will continue to support the “One China” policy, opposes “Taiwan independence” in any form, rejects Taiwan’s accession to international organizations, which can only be joined by sovereign states, and will not have any official contacts with Taiwan.”[35]

While Ukraine was adhering to the above-mentioned positions, disregarding even the quite legitimate possibility of establishing economic relations with Taiwan, the PRC ignored the commitments made in the Joint Statement: “The Chinese side reaffirms respect for the independence of Ukraine, its sovereignty and territorial integrity. The Chinese Side highly appreciates the decision of the Ukrainian Side to unilaterally get rid of nuclear weapons and Ukraine’s accession to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons as a non-nuclear-weapon state, and also confirms that according to the Statement of the Government of the People’s Republic of China of 1994, China’s principled position on the non-use or threat of use of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states and nuclear-weapon-free zones applies to Ukraine.”[36]

In fact, the Chinese side was and remains not only passive in supporting Ukraine in the context of Russian aggression since 2014, but, on the contrary, covertly assisted Russia in its unlawful actions on the illegally annexed Crimean peninsula. While verbally declaring the PRC’s commitment to the principles of sovereignty, territorial integrity, non-interference in internal affairs, in practice Beijing assisted the aggressor by refusing to impose sanctions, as well as by helping in the implementation of a strategically important project—the energy bridge to the occupied Crimea through the Kerch Strait. The latter would have been impossible without the participation of foreign companies. To help the aggressor, Beijing provided Chinese contractors Jiangsu Hengtong HV Power System and Shanghai Foundation Engineering Group Co, Ltd. together with a specialized cable-laying vessel JIAN JI 3001[37].

We can also observe China’s complete inaction in counteracting Russia’s nuclear blackmail of Ukraine. Despite the dubiousness of the idea of inviting China to the circle of guarantors of Ukraine’s security, Kyiv in April 2022 invited Beijing to join. According to Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba, such a gesture “is a sign of our respect and trust in the People’s Republic of China.”[38] For six months, no official reaction has been received from Beijing, but every day Chinese propaganda mouthpieces accuse the US and NATO of the “war in Ukraine,” following the narratives of Russian propaganda. The positive thing is that Ukraine’s leadership had enough common sense to abandon the ill-conceived idea of seeing China as a security guarantor.

Today, a group of MPs in the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine has created an inter-factional association to support cooperation with Taiwan. Work is underway to open a representative office of Taipei in Kyiv and a representative office of Ukraine in Taipei. Beijing perceives such steps of other states as rather “provocative,” but Ukraine has enough room for maneuver.

It is noteworthy that the Russian Federation has an embassy in Taiwan, and in Russian it is referred to as an embassy (Embassy of Russia in Taipei)[39] on diplomatic resources, although in English it is designated as the Representative Office of Russia in Taipei. The working mechanism of Russian-Taiwanese relations is the Moscow-Taipei Coordination Commission on Economic and Cultural Cooperation (MTC).

China’s reaction and inaction regarding Russia’s war against Ukraine actually leveled the already dubious document on strategic partnership with Ukraine, which was concluded in 2011. One cannot be both a strategic partner of the aggressor state and a state that is a victim of aggression. China’s abstention from voting in the UN on October 12 on the resolution “Territorial integrity of Ukraine: defending the principles of the Charter of the United Nations” is an additional evidence of the falsity of not only Beijing’s declared recognition of the territorial integrity of Ukraine, but also passive solidarity with the Russian position.

4. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

- Ukraine’s foreign policy in the East Asian direction is anachronistic, unreasonably Beijing-centric, does not correspond to the state of affairs of the war period and needs to be corrected.

- Strengthening relations with Japan, which will preside over the G7 next year and will be a non-permanent member of the UN Security Council in 2023-2025, is essential in the context of political and diplomatic counteraction to Russia and post-war reconstruction of Ukraine.

- Relations with South Korea are important from the perspective of the possibility of joining the sanctions against Russia and purchasing high-tech equipment and components as a reasonable alternative to the products of Chinese and Western manufacturers.

- Having formally distanced from Moscow to some extent due to the defeats of the Russian army in Ukraine, Beijing nevertheless remains on its side. Increased purchases of Russian oil boost Russia’s revenues. At the same time, by limiting the opportunities for the sale of Ukrainian products and replacing their supply with Russian and other sources, Beijing is programming a decrease in Ukraine’s revenues from exports to China. The result is the deterioration of Ukraine’s already negative trade balance with China and the increase in Russia’s export revenues, which sustain Russia’s ability to continue its aggression against Ukraine.

- Given the context of Ukraine’s European and Euro-Atlantic integration, Kyiv, building further relations with Beijing, should not only take into account the policy of containment of China by the United States and the EU, but also be a party to this policy.

- To work out the issue of adjusting Ukraine’s strategy towards China, remaining in the format of “One China” relations, while making gestures of attention to Taiwan. The strategic partnership between Ukraine and China, fixed by the shady declaration of 2011, has not passed the test of Russian aggression against Ukraine. Beijing, formally declaring support for the territorial integrity of Ukraine, actually plays on the side of the aggressor, reproducing the narratives of the Kremlin’s propaganda both domestically and internationally.

- When rethinking approaches, the following should be taken into account:

- 7.1. Ukrainian-Chinese trade is shifting more and more towards a negative balance for Ukraine;

- 7.2. The June 20, 2011 Joint Declaration on Establishment and Development of Strategic Partnership Relations between Ukraine and the People’s Republic of China signed during the Yanukovych regime is a dubious document, concluded shortly after the inter-party Agreement on Cooperation between the Party of Regions and the Communist Party of China, which asymmetrically reflects the strategic interests of the parties (the document is not available in the official database);

- 7.3. China’s actions do not correspond to the spirit of the proclaimed strategic partnership as the assistance of Chinese companies in the construction of the Kerch energy bridge to the occupied Crimea, the case with the clandestine alienation of Motor Sich in favor of a Chinese company, the agreement with Russia on the non-infringement of Chinese investors’ assets in southern Ukraine are evidence that Beijing is acting in a way that takes into account Moscow’s interests and ignores those of Kyiv;

- 7.4. Beijing does not support the sanctions regime against the Russian Federation, although it should at least partially join it, considering last year’s and this year’s scandalous agreement of Ukraine under pressure from China to refuse to sign the UN Human Rights Council’s statement on the Uyghur genocide, which was initiated by Canada and supported by all Western countries;

- 7.5. Chinese exports to Russia of microchips and materials, including those with military applications, have increased dramatically since February 24, complicating the sanctions efforts of the United States and its allies;

- 7.6. China has stepped up imports of Russian oil, thereby increasing Russia’s revenues and its ability to continue its aggression;

- 7.7. Since February 25, Taiwan has de facto stopped exporting microprocessors to Russia, and since April 6 has introduced de jure export controls[40];

- 7.8. Taiwan has provided Ukraine with ten times more assistance to refugees than China.

- In view of the above, the following seems appropriate:

- 8.1. To work out the issue of opening the Ukrainian office in Taipei according to the pattern that complies with the established international practice for the case of Taiwan. In total, 71 representative offices of foreign countries have been opened in Taiwan under this scheme, which de facto serve as diplomatic institutions[41]. 8.2. It is important that the name of the representative office does not include the name of the island (Taiwan), but the name of the capital (Taipei).

- 8.3. The models for emulation are the following—Polish Office in Taipei, Czech Economic and Cultural Office in Taipei, Slovak Economic and Cultural Office in Taipei, Representative Office of Finland in Taipei.

- 8.4. Another option of presence is through the representation of a non-profit organization by analogy with the American Institute in Taiwan, which replaced the US Embassy after the termination of diplomatic relations in 1979 and works under the supervision of the US Congress. According to the same scheme—the German Institute of Taipei—the official Berlin works with Taiwan.

- The front for the Ukrainian presence in Taiwan could be the Representative Office of the Ukrainian Institute in Taipei with the tasks of cultural diplomacy and educational exchanges. At the same time, a bureau of a Ukrainian non-governmental organization (similar to the Czech NGO “European Values”) can be opened, which will serve as a cover for the necessary contacts on military-technical cooperation and other sensitive issues. Also, based on the principle of reciprocity, a Representative Office of Taipei can be opened in Kyiv, as in all other cases of foreign countries.

References

- http://ua.china-embassy.gov.cn/rus/zwgx/201009/t20100906_3206513.htm

- https://chinaobservers.eu/the-enemy-of-my-friend-remains-my-friend-chinas-ukraine-dilemma/

- https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/ov/speech_22_5493

- https://espreso.tv/article/2016/05/04/chy_zmozhe_rosiya_zrobyty_krym_energonezalezhnym

- https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/28/2002964702/-1/-1/1/NDS-FACT-SHEET.PDF

- https://sanctionsnews.bakermckenzie.com/taiwan-issues-list-of-russia-related-export-controls/

- https://thediplomat.com/2022/03/the-cost-of-the-war-to-the-china-ukraine-relationship/

- https://thegeopolitics.com/chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-an-overview/

- https://tsn.ua/svit/ukrayina-ta-kitay-vitratyat-7-milyardiv-dolariv-na-vtilennya-spilnih-proektiv-1055860.html

- https://ua.usembassy.gov/uk/u-s-ukraine-charter-on-strategic-partnership/

- https://www.clingendael.org/publication/new-map-belt-and-road-initiative

- https://www.embassypages.com/taiwan

- https://www.epravda.com.ua/publications/2022/03/22/684453/

- https://www.facebook.com/cesukraine/posts/4871476329547259

- https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202204/1259758.shtml

- https://www.niknews.mk.ua/2015/01/20/biznesmen-iz-gonkonga-zajavil-prava-na-kuplennyj-knr-u-ukrainy-avianosets-varjag/

- https://www.posolstva.net/ru/26380/Russia-embassy-Taipei

- https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/3922020-35037

- https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/4482021-40017

- https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/6922022-44369

- https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/kytai-ukrayina-investytsiyi-kredyty-knr-kpk/31487078.html

- https://www.rbc.ua/rus/news/svoyi-interesi-chiemu-botsi-kitay-viyni-rosiyi-1664467503.html

- https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/uk/news/20220930_41/

- https://z-upload.facebook.com/embassyofjapaninukraine/posts/1970161626511054

[1] https://z-upload.facebook.com/embassyofjapaninukraine/posts/1970161626511054

[2] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/ov/speech_22_5493

[3] https://media.defense.gov/2022/Mar/28/2002964702/-1/-1/1/NDS-FACT-SHEET.PDF

[4] https://ua.usembassy.gov/uk/u-s-ukraine-charter-on-strategic-partnership/

[5] https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/3922020-35037

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/4482021-40017

[8] Ibid.

[9] https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/3922020-35037

[10] Ibid.

[11] https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/4482021-40017

[12] https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/4482021-40017

[13] Ibid.

[14] https://www.president.gov.ua/documents/6922022-44369

[15] https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/uk/news/20220930_41/

[16] https://z-upload.facebook.com/embassyofjapaninukraine/posts/1970161626511054

[17] https://thediplomat.com/2022/03/the-cost-of-the-war-to-the-china-ukraine-relationship/

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] https://chinaobservers.eu/the-enemy-of-my-friend-remains-my-friend-chinas-ukraine-dilemma/

[21] https://thediplomat.com/2022/03/the-cost-of-the-war-to-the-china-ukraine-relationship/

[22] Ibid.

[23] https://www.epravda.com.ua/publications/2022/03/22/684453/

[24] https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/kytai-ukrayina-investytsiyi-kredyty-knr-kpk/31487078.html

[25] https://www.facebook.com/cesukraine/posts/4871476329547259

[26] https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/kytai-ukrayina-investytsiyi-kredyty-knr-kpk/31487078.html

[27] Ibid.

[28] https://tsn.ua/svit/ukrayina-ta-kitay-vitratyat-7-milyardiv-dolariv-na-vtilennya-spilnih-proektiv-1055860.html

[29] https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/kytai-ukrayina-investytsiyi-kredyty-knr-kpk/31487078.html

[30] https://www.niknews.mk.ua/2015/01/20/biznesmen-iz-gonkonga-zajavil-prava-na-kuplennyj-knr-u-ukrainy-avianosets-varjag/

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202204/1259758.shtml

[34] https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202204/1259758.shtml

[35] http://ua.china-embassy.gov.cn/rus/zwgx/201009/t20100906_3206513.htm

[36] Ibid.

[37] https://espreso.tv/article/2016/05/04/chy_zmozhe_rosiya_zrobyty_krym_energonezalezhnym

[38] https://www.rbc.ua/rus/news/svoyi-interesi-chiemu-botsi-kitay-viyni-rosiyi-1664467503.html

[39] https://www.posolstva.net/ru/26380/Russia-embassy-Taipei

[40] https://sanctionsnews.bakermckenzie.com/taiwan-issues-list-of-russia-related-export-controls/

[41] https://www.embassypages.com/taiwan

© Centre for Global Studies «Strategy ХХІ»

Group of authors:

Mykhailo Honchar, Serhii Vyshnivetskyi, Oksana Bukovynska, Oksana Ishchuk

The information and views set out in this study are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine.

Centre for Global Studies «Strategy ХХІ»

Shchekavytska str, 51 office 26

Kyiv, 04071, Ukraine

Е-mail: info@geostrategy.org.ua